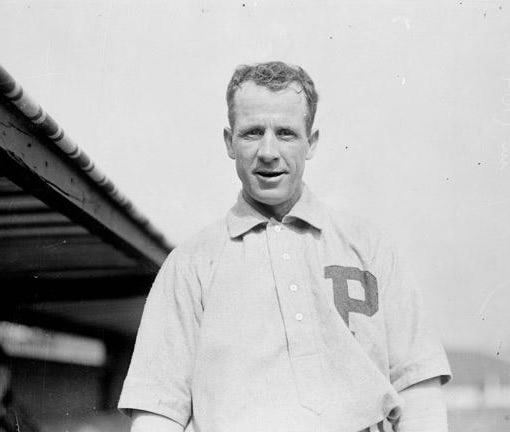

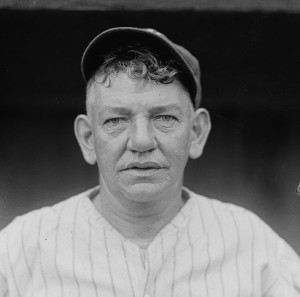

Kid Gleason, inaugural member of the Hall of Clearly Above Replacement by Not Quite Average

(image via Wikimedia Commons)

You have probably heard about the new Hall of Nearly Great eBook. It is a project curated by Sky Kalkman and Marc Normandin that celebrates some of the forgotten greats of the game. The fact that a player is not a Hall of Famer doesn’t mean he shouldn’t be remembered.

One morning, I was looking at the ebook’s table of contents along with my wWAR spreadsheets. I found that (of course) there are enough great players outside of the Hall of Fame to fill several volumes of Hall of Nearly Great books. As comprehensive as the Sky and Marc’s book was, there were still players like Dave Stieb, Wes Ferrell, Ken Boyer, Ron Guidry, Vida Blue, Deacon White, Doc Gooden, and so, so many others. I posted some of these names on Twitter.

My friend Dan McCloskey tweeted back:

“Once they work down to the Hall of Clearly Above Replacement But Not Quite Average, I want to contribute.”

I doubt Sky and Marc will reach down that far, so that’s what Dan and I are organizing today. Consider this an homage to the Hall of Nearly Great. Just like the book, we’re going to cover 43 players. Just like the book, we’ve invited some guest authors. Unlike the book, we don’t have an author for each player. Also, we’re capping the player bios at 100 words. This is a blog post, not a book!

Today, we give you The Hall of Clearly Above Replacement, But Not Quite Average.

Criteria

For a player to be considered for this honor, he must have a career Baseball-Reference Wins Above Replacement (WAR) above 8.0—but have a Wins Above Average (WAA) total less than zero. In other words, he needs to be above replacement, but below average. In yet another set of other words, he needs to be below average, but still useful.

What’s the Difference Between WAR and WAA?

All components of WAR are expressed in runs above or below average, not replacement. These numbers are then added up and a replacement adjustment is made. WAA is basically WAR without this replacement adjustment. Last week, my first High Heat Stats article covered the difference between WAR and WAA in detail.

The Authors

We have six talented authors. I also contributed, giving us a total of seven.

- Andy (@HighHeatStats) is… well, if you’re reading this blog, you should already know what he is.

- Dan McCloskey (@_LeftField) is a husband, a new father, a Systems Librarian by day, a music-obsessed baseball fanatic—who’s been to 24 Hall of Fame induction ceremonies—and craft beer enthusiast in his (very limited) free time. Most of his work can be found at his personal blog, Left Field.

- Stacey Gotsulias (@StaceyGotsulias) writes words about baseball for Aerys Sports and The Yankee Analysts. When she’s not hanging out at home with her five cats (No, that’s not a typo), she can be found in the last row of the Yankee Stadium upper deck cheering on the boys from the Bronx.

- Born and raised in southern New England, Bill Miller (@Raindog63), a life-long Mets fan, now lives and blogs in Greenville, S.C., where to criticize Shoeless Joe Jackson is akin to casting aspersions upon Jesus, College Football, and the old Confederacy, not necessarily in that order.

- Graham Womack (@grahamdude) is the founder and editor of Baseball: Past and Present as well as a contributor to this website.

- Bryan O’Connor writes about MVP races, Hall of Fame cases, and how to evaluate aces at Replacement Level Baseball Blog. A nonprofit accountant, advocate for equal rights, and Fangraphs devotee, Bryan lives with his wifeand two young children in South Portland, Maine.

- Adam Darowski (@baseballtwit) is a husband, dad of three, a web developer, and a baseball researcher focused on the Hall of Fame. Much of his research can be found at the Hall of wWAR. He writes for Beyond the Box Score, Baseball: Past and Present, and this site.

Next, Your Turn

We covered 43 players, but there 441 who fit our criteria. You can find the rest in this Google Spreadsheet. If you see someone you like, please take part. Pick a player and write 100 words about him. These were useful players who deserve to be remembered.

The Players

Here they are, sorted by WAR.

Kid Gleason (1888-1908, 1912; 35.5 WAR; –3.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Kid Gleason, most famous for managing the 1919 White Sox, was by far the most successful player in this Hall. He collected nearly 2,000 hits as a second baseman and also earned 138 victories on the mound, peaking with 38 wins in 1890. He was a much more valuable pitcher (29.4 WAR/11.7 WAA) than a hitter (6.1 WAR/–15.1 WAA), but when you merge his numbers, they fit the criteria. No player in history has hit as often and pitched as often as Gleason (though John Montgomery Ward comes very close on both counts).

Joe Niekro (1967-1988; 26.2 WAR; –1.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

I suspect people think Joe and Phil Niekro were closer in value than they really were. The truth is, the knuckleballing brothers had a WAA disparity nearly as large as Cal and Billy Ripken (57.8 difference to 53.2). Joe accumulated 26.2 WAR by hanging around for a long time. His 500 starts rank 45th all time while his innings total ranks 63rd (he’s even 101st in strikeouts). He was at his best with Houston, the team for which he still owns the win record. Niekro won twenty games twice, but peaked in 1982 (with 17 wins and 6.5 WAR at age 37).

Lew Burdette (1950-1967; 24.8 WAR; –1.0 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

I was surprised to see that Lew Burdette (who received 24% of the Hall of Fame vote in 1984) was a slightly below average pitcher. The 1957 World Series MVP won 203 games with a sparkling .585 winning percentage, but his 3.66 ERA translates to just a 99 ERA+. While his ten-year peak produced 163 wins (fourth from 1952 to 1961) against only 106 losses, it only produced 23.9 WAR (placing 14th) and 3.6 WAA (his non-peak years brought those numbers down further). One might suggest that many of those wins belong more to Henry Aaron and Eddie Mathews than Burdette.

Don Baylor (1970-1988; 24.4 WAR; –2.4 WAA)

by Graham Womack

It seems counter-intuitive to think of a player with 330 home runs, a 118 OPS+ and 24.4 WAR as a below average player. Maybe that’s the essence of this project. Look a little deeper with Don Baylor and there are plenty of things to justify the –2.4 Wins Above Average that he compiled over the course of his career. There’s his –22.9 defensive WAR, his rating for the stat negative 16 of his 19 seasons. And for supposedly making his mark at the plate, Baylor batted .260 lifetime, hitting above .300 and posting a slugging line above .500 just one time apiece for each stat.

Chris Chambliss, the owner of 23.4 WAR, still comes in slightly below average.(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Chris Chambliss (1971-1986, 1988; 23.4 WAR; –1.4 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Having grown up a Yankees fan who counts Chris Chambliss’s walk-off home run to clinch the 1976 ALCS among my first baseball memories, it’s hard to think of him as below average. In fact, his 23.4 WAR ranks among the highest of players who satisfy the criteria for this project, as he was better than replacement for 15 of his 17 major league seasons. Chambliss enjoyed his best regular season in 1976 as well, hitting 17 homers and driving in 96 runs to go with a 124 OPS+ and 3.8 WAR, and tying Rod Carew for 5th in MVP voting.

Joe Kuhel (1930-1947; 21.8 WAR; –2.9 WAA)

by Graham Womack

Joe Kuhel was an American League first baseman from 1930 to 1947, a Golden Age for that position in that circuit. When people talk of standout AL first basemen from those days, I suspect they talk of Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg and Jimmie Foxx and, to a lesser extent, Hal Trosky, Zeke Bonura and Rudy York. I’ve never heard anyone pay tribute to Joe Kuhel, and there’s good reason for this. There’s nothing memorable about a player who averaged seven home runs a year in the 1930s and later had a .257/.352/.349 slash line playing through World War II because he was past draft age. It makes sense Kuhel finished with –2.9 Wins Above Average.

Joe Vosmik (1930-1941, 1944; 18.6 WAR; –0.5 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Joe Vosmik, the son of Bohemian immigrants, was born in Cleveland and starred for the Indians (while later playing for Browns, Red Sox, Dodgers, and Senators). He played during the offensive explosion of the 1930s, posting his best season in 1935 (when he led the league in hits, doubles, and triples while hitting .348 with 5.6 WAR). He hit .300 five other times and owned a career average of .307. Due to the era, that only translates to an OPS+ of 104. He fanned just 272 times in 6088 career PAs, whiffing only 10 times while hitting .341 in 1934.

Orlando Cabrera (1997-2011; 18.1 WAR; –5.2 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

What I remember second-most about Orlando Cabrera (after whom I once named a goldfish) was the Gold Glove he won in 2001, when I still cared who won Gold Gloves. His Jekyll-and-Hyde UZR history half-belies his excellent defensive reputation, but the Gold Glove voters were surprisingly observant, rewarding him in two seasons in which UZR tells us he saved double-digit runs with his glove. What I remember most is his effect on the 2004 Red Sox, from the home run he hit in his first at-bat with the team to his ten-game postseason hitting streak to the personalized handshakes he invented for every one of his teammates. My all-time favorite player played 58 regular season games for my favorite team.

Jim Clancy (1977-1991; 17.9 WAR; –1.2 WAA)

by Andy

Jim Clancy is widely remembered as the pitcher with the most losses in the 1980s. The reality is that he was a very reliable starter for an average team. Between 1980 and 1987 Clancy was one of just 10 pitchers with at least 5 seasons of 120 IP and an ERA+ of 109. Fantastic he wasn’t, but dependable he was. He posted 4 different seasons with at least 3 WAR and only a couple worse than –1 WAR. In just this time with Toronto, Clancy accumulated 22.6 WAR and 5.5 WAA—a nice career. It was his few bad years in Houston and Atlanta that dragged down his totals.

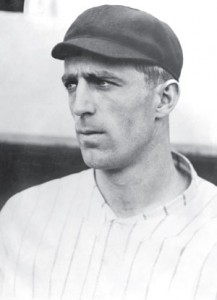

<Boner Joke Redacted> (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Fred Merkle (1907-1920, 1925-1926; 17.6 WAR; –0.6 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

Even more than Bill Clinton or the sitcom Growing Pains, Fred Merkle is best known for a costly boner. Merkle likely cost his Giants the pennant in 1908 by not touching second base on what looked like a game-winning single by teammate Al Bridwell. Lost in this unfortunate legacy is a solid career, featuring an OPS ten percent better than league average over sixteen seasons, five of which ended with trips to the World Series. Sadly, like the 1908 season Merkle would have loved to erase, those World Series trips all ended with Merkle’s team—whether the Giants, Dodgers, or Cubs—losing its final game.

Jack Tobin (1914-1916, 1918-1927; 17.4 WAR; –1.7 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Jack Tobin was one of the stars of the Federal League in 1915, the final season of its two-year existence, and was the second most valuable position player (by WAR) for the league champion St. Louis Terriers. His 184 hits led the league, and he also ranked tied for fourth in runs, third in total bases, and in the top ten in doubles, triples, home runs, walks and stolen bases. After the league folded, he moved across town to play with the AL’s St. Louis Browns for nine seasons, playing third-fiddle in outfields alongside Ken Williams and Baby Doll Jacobson.

George Bell (1981, 1983-1993; 17.0 WAR; –1.6 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

When I saw George Bell’s name on the eligible list, two thoughts came immediately. The first was that Bell’s 1986 Topps baseball card called him Jorge, while the previous and subsequent years’ cards displayed his anglicized name. The second thought was outrage at one of the heroes of my youth—the 1987 AL MVP!—might be considered below average. Further investigation revealed that the years had exaggerated the numbers on the back of Senor Bell’s tarjeta de beisbol. He slugged .605 in ’87, but reached .500 only once more in his relatively short career. He struck out more than twice as much as he walked and led all left fielders in errors three straight years in his prime. Another hero deflated.

Pete O’Brien (1982-1993; 16.5 WAR; –1.1 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Talk about playing in the wrong position at the wrong time. Poor Pete O’Brien was a pretty good first baseman but he played at the same time as guys like Don Mattingly, Eddie Murray and Wally Joyner. Because of this cruel twist of fate, O’Brien never made an All-Star team. His career lasted from 1982-1993 and one time, in 1986, he was 17th in MVP voting. He finished his career .261/.336/.409/.725.

Ray Sadecki (1960-1977; 16.4 WAR; –3.7 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Ray Sadecki’s first season in the Majors in 1960 saw him finish 9-9 with a 3.78 ERA. After 18 years Sadecki finished his career with a 135-131 record and 3.78 ERA. In between, he was up, down and all around, played with six teams and helped the St. Louis Cardinals to a World Series title in 1964. To be fair, Sadecki helped the 1964 St Louis Cardinals to a World Series much in the way that Kenny Rogers helped the 1996 New York Yankees to a World Series title, he’d give up a bunch of runs and have to be relieved early.

Jeff Conine (1990, 1992-2007; 16.0 WAR; –5.9 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Did you know that Jeff Conine was originally a pitcher? He was taught how to play in the outfield before his Rookie of the Year campaign in 1993 with the Florida Marlins. The two-time World Series champion was a solid player during his 17-year career finishing with a line of .285/.347/.443/.789 and 214 home runs. His best years were early and while he was with the Marlins. He ended up playing with six teams before retiring in 2007.

Felix Millan (1966-1977; 15.9 WAR; –2.7 WAA)

by Bill Miller

Second baseman Felix Millan played for the Braves and Mets from 1966-77. His lack of power (22 career homers) and sluggish career OBP (.322) was partially offset by his ability to make contact. He was the toughest N.L. batter to strikeout four times in the 1970’s. Millan held the Mets record for hits in a season (191 in 1975) until Lance Johnson broke the record in 1996. His career WAR (16.9) is primarily a testament to his solid defense. Millan’s career ended prematurely in ’77 when Pirates catcher Ed Ott used Millan as a pile-driver during a scuffle at second base.

Mike Caldwell (1971-1984; 15.9 WAR; –2.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Mike Caldwell was a classic Yankee killer, going 13-8 with a 3.05 ERA and five of his 23 career shutouts against the Bronx Bombers. He finished second to Ron Guidry in AL Cy Young voting in 1978, and was responsible for handing Guidry one of just three losses that year. A late bloomer who wouldn’t have made this list if not for a sub-par early career, he also ranks second on the all-time Milwaukee Brewers list in wins (102) and was 2-0 with a 2.04 ERA in their 1982 World Series loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Joe Carter (1983-1998; 15.6 WAR; –10.8 WAA)

by Andy

Joe Carter is not a star—he’s the very definition of an average player. In 1990, Carter put up 115 RBI and got noticed nationally. The neat trick is that he drove in all those runs with just an 85 OPS+, the lowest OPS+ all-time for a player with at least 111 RBI in a season. Carter, in 1997, also had the lowest OPS+ (77) all-time of any player with at least 102 RBI in a season. Over his career, he was given a ton of RBI opportunities. In 1990, for example, 26.9% of all NL plate appearances came with runners in scoring position. For Carter that year, the figure was 33.1%. He did decently with what he was given, and that’s what he was as a player–decent.

I know this is Dave Kingman, but I have no idea what the hell he’s doing here. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Dave Kingman (1971-1986; 14.7 WAR; –6.7 WAA)

by Bill Miller

Whatever block of wood Dave Kingman was carved out of was tall, narrow, and devoid of mirth. His 442 career homers threw a scare into many that, if he stuck around long enough to hit 500, it would present difficulties come HOF voting time, for Kingman was a terrible player. Luckily, the Kingman show (strikeout / home run) was cancelled after 16 seasons with seven teams. Led his league in home runs twice, strikeouts three times and pleasant interviews never. Came up as a pitcher, but impersonated a position player for several years before his glove was taken away and buried.

Del Unser (1968-1982; 14.4 WAR; –2.7 WAA)

by Bill Miller

In his best season, Del Unser batted leadoff (someone had to) and played centerfield for the ’75 Mets. With a little hitch in his swing, Unser hit line-drives (with a smidgen of power) for five teams in 15 years. Unser was prone to the acrobatic catch in centerfield, perhaps mimicking PHEENOM Freddy Lynn of Boston. Later in his career, after a trade to Philadelphia, Unser sported a porn-star mustache. The direct impact of said mustache upon his baseball career is ambiguous, but this .258 career hitter (who once led the league in triples) was essentially done in the Majors by age 35.

Jody Reed (1987-1997; 14.0 WAR; –1.1 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

If you Googled Jody Reed today, you’d think the only thing he ever did was make a huge contract gaffe. After the 1993 season, he chose not to accept a three-year deal with the Dodgers worth $7.8 million. He would eventually sign with Milwaukee for the minimum. I remember Reed as something of an early day Dustin Pedroia. The numbers don’t come close to backing that up, but he was worth 12.9 WAR from 1988 to 1991 for the Red Sox. He led the AL with 45 doubles in 1990 and topped 40 two other times.

Lee Mazzilli (1976-1989; 13.9 WAR; –0.4 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Lee Mazzilli was supposed to be a superstar, but things didn’t quite work out that way. While he did flash his star potential early on with the Mets (peaking at 4.7 WAR in 1979), for most of his career he was just a solid bench player. That’s exactly what he was when he returned to his hometown team (after being traded to Texas for Ron Darling, followed by stints with the Yankees and Pirates) in 1986. As a key pinch-hitter, Mazz contributed hits to game-tying rallies in both games six and seven of the Mets’ 1986 World Series victory.

Brad Ausmus (1993-2010; 13.6 WAR; –5.8 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

There aren’t many people who caught as much—and as well—as Brad Ausmus. The Ivy League (Dartmouth) backstop ranks 7th in games caught, 9th in Total Zone runs (99), and even 11th in our old friend Fielding Percentage (.994). While could catch, he certainly couldn’t hit much—his .251/.325/.344 slash line during the height of the offensive explosion gives him an OPS+ of just 75 (and –215 WAR batting runs). No Jewish player has appeared in more big league games than Ausmus, who will manage Team Israel at the 2013 World Baseball Classic.

Everett Scott (1914-1926; 12.6 WAR; –8.3 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

When Lou Gehrig played in his 1,308th consecutive game, he broke the record held by Everett Scott. Within the first five seasons of his career, Scott had already won three world championships as the light-hitting (65 OPS+)/slick fielding (+95 WAR fielding runs) shortstop and captain of the Boston Red Sox. After the 1921 season, Scott was traded to the Yankees and became captain of the Bronx Bombers, as well. He won another championship in New York (in 1923). Lou Gehrig began his consecutive games streak two days after Scott’s final game as a Yankee.

Tito Francona (1956-1970; 11.9 WAR; –4.4 WAA)

by Bryan O’Connor

Among baseball players who contributed more to the game through their progeny than through their own accolades, Tito Francona may not be Bobby Bonds or Ken Griffey, but he did sire perhaps the best manager in Red Sox history and one of its best budding color commentators. To ignore the elder Francona’s own ledger, though, is to miss a player who hit more home runs (125) than Ty Cobb and had the same career on-base percentage (.343) as Lou Brock. Accumulated in parts of 15 seasons, Tito’s 11.9 WAR (per Fangraphs) were 15.5 more than his son earned.

Rob Deer (1984-1993, 1996; 11.8 WAR; –1.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Oh my, Rob Deer was glorious. In 4,513 times at bat, Deer launched 230 home runs, walked 575 times, and fanned 1,409 times. Those three true outcomes and accounted for 49% of Deer’s plate appearances. One of the most amazing stat lines I’ve seen is Deer’s 25-game comeback with the Padres in 1996—64 PAs, 9 hits, 4 homers, 14 walks, 30 strikeouts, a .180/.359/.839 slash line, and an OPS of 125. In 1991, Deer had another ridiculous season, hitting .179 while qualifying for the batting title (a record low). He homered 25 times, walked 89 times, and whiffed 175 times. Rob Flipping Deer.

Bobby Witt (1986-2001; 11.8 WAR; –8.1 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Before there was Armando Galarraga, there was Bobby Witt. On June 23, 1994, Witt came painfully close to perfection. Greg Gagne was ruled safe on a sixth inning bunt although replays showed he was safe. He was the only baserunner Witt allowed while fanning fourteen. From 1986 to 1988, Witt joined teammate Mitch Williams in walking 604 batters (while fanning 762 and throwing 59 wild pitches) in 750 innings. Any time you meet Gene Petralli, Don Slaught, or Mike Stanley (their catchers), go easy on them. They also caught Charlie Hough.

Despite 2715 hits, Bill Buckner was a below average hitter. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Bill Buckner (1969-1990; 11.8 WAR; –17.2 WAA)

by Graham Womack

Bill Buckner was a good contact hitter, an RBI machine and he probably took undue grief from beleaguered Red Sox fans for muffing that ground ball in the 1986 World Series. After all, Buckner alone didn’t lose the championship. Regardless, the error pits Buckner with fellow goats like Fred Snodgrass and Fred Merkle and in comparison, Buckner suffers. Where Snodgrass compiled 4.4 Wins Above Average during his career and Merkle was at –0.6 WAA, Buckner amassed a ghastly -17.2 WAA. That’s the lowest of any man in this project, Buckner’s meager power, OBP and defense relegating him to a spot in sabermetric history worse than anything Game 6 could’ve provided.

Matt Stairs (1992-1993, 1995-2011; 11.7 WAR; –6.3 WAA)

by Andy

Matt Stairs topped 500 plate appearances in only 3 of his 19 seasons in the big leagues. A very poor defender, his –17.3 dWAR nearly negated all of his 20.4 oWAR, earned because the man carried a giant stick. Stairs holds the MLB record with 23 pinch-hit homers, which came in 490 plate appearances, and usually against ace relievers. He’s tied with Wally Schang for highest career OPS+ (117) among non-pitchers with at least 13 MLB seasons of 410 plate appearances or fewer. Stairs kept it up in the post-season, with a memorable pinch-homer in Game 4 of the 2008 NLCS, helping the Phillies beat the Dodgers.

Jack Graney (1908, 1910-1922; 11.6 WAR; –7.4 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

Jack Graney’s career was full of firsts. He was the first batter to face Babe Ruth. He was the first official player to wear a uniform number. But, he is remembered most for being the first major league player-turned-broadcaster. The Canadian leftfielder followed up his 14-year Major League career (featuring a 101 OPS+ in 5,581 PAs—all with the Indians) by broadcasting Cleveland Indians games on the radio from 1932 to 1953. From a sabermetric perspective, he is the player with the highest career WAR (11.7) who never had a single above-average seasons (according to WAA).

Dick Tidrow (1972-1984; 11.2 WAR; –2.0 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

Back in the days when effective relievers pitched 100+ innings a year, Tidrow was briefly one of the best setup men in baseball, although he had to go through some growing pains as a starter first. After three up-and-down seasons in Cleveland and New York, the Yankees moved him to the bullpen, where he posted a 126 ERA+ and was worth 4.2 WAR the next three years. Another failed attempt to start and a trade to the Cubs later, Tidrow had his two best seasons back in the bullpen (219 IP, 147 ERA+, 5.3 WAR) before fading into negative-WAA oblivion.

John Milner (1971-1982; 11.1 WAR; –0.3 WAA)

by Bill Miller

John “The Hammer” Milner was a first baseman/leftfielder who player primarily for the Mets and the Pirates from 1971-82. Through his age 24-season, he’d already slugged 60 home runs. He always appeared to be one small step away from stardom, but his home parks (especially Shea Stadium) and the era in which he played tamped down his production. Milner drew more walks (504) than strikeouts (473) in his career. His career OPS+ (112) is the same as HOFers, Sam Rice, George Kell… and some guy named Cal Ripken, Jr.

Chick Fraser (1896-1909; 10.7 WAR; –14.0 WAA)

by Graham Womack

Chick Fraser’s 3.67 ERA looks conspicuously out of place for a man whose career spanned 1896 to 1909, part of what we now call the Deadball Era. His 92 ERA+ is tied for tenth-worst among pitchers with at least 1,000 innings logged in those years, and none of the men in front of Fraser came anywhere close to his 3,364 innings. In fact, Fraser has the worst ERA+ of any pitcher in baseball history with at least 3,000 innings. If we drop it to 2,000 innings, he’s ninth-worst. Whatever the case, Fraser’s –11.2 Wins Above Average doesn’t look like any kind of sabermetric slight. He was historically bad and has a deserved place in this project.

Vince Coleman (1985-1997; 10.5 WAR; –6.6 WAA)

by Andy

Vince Coleman turned the NL on its ear when he arrived in 1985. This young firecracker led the league in stolen bases in each of his first 6 years. Surely he created a lot of value and it’s a mistake that he’s on this list, right? Wrong. The guy was at best an average hitter and had very little power. Over that 6-year period of 1985-1990, while he led MLB in stolen bases, he also led in caught stealing, managed just an 85 OPS+, generated just 11.0 WAR, and was below average at –0.4 WAA. And that was his career peak. Once he left St. Louis, he put up near-zero WAR the rest of the way.

Lee Richmond (1879-1883, 1886; 10.3 WAR; –2.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

It’s probably the case with all of the players discussed here that their careers, while considered below average by modern metrics, actually include some exceptional moments. Lee Richmond might be the ultimate example, having thrown the first perfect game in Major League history on June 12, 1880. In fact, his perfect game occurred before the term had even been coined. He compiled almost his entire career pitching value in 1880, his rookie season, going 32-32 with a 2.15 ERA and 119 ERA+ in 590 2/3 innings for the Worcester Ruby Legs, and accumulating 7.6 WAR.

Tony Clark (1995-2009; 10.1 WAR; –4.7 WAA)

by Andy

Tony Clark was a stud with the Tigers in the late 1990s. He averaged 32 HR, 106 RBI, and 125 OPS+ in 1997-1999, his first 3 full seasons in the big leagues. Unfortunately, those also turned out to be his last 3 full seasons, thanks to a seemingly endless string of injuries.Over the final 10 years of his career, he averaged just 97 games with a 106 OPS+. As a below average defender, his WAR suffered badly over those 10 years, except for 2005, when, in his finest hour as a major-leaguer, he produced 30 HR, 87 RBI, and 3.2 WAR for the Diamondbacks in just 393 plate appearances.

Lenny Randle (1971-1982; 9.7 WAR; –3.4 WAA)

by Bill Miller

After a few uninspiring seasons out in Texas (really, can you blame him?), third baseman Lenny Randle became the toast of Shea Stadium in 1977. Randle came to the Mets with a reputation for being surly (a term white reporters reserve for black players), but won over Mets fans with his speed (33 steals), his ability to get on base (.383 on-base percentage) and solid, sometimes spectacular defense. Unfortunately for Randle and the Mets, his age-28 season was not to be replicated. Marooned with the Mariners, Randle retired from baseball in 1982 with a desultory .257 career batting average.

Paul Foytack (1953, 1955-1964; 9.0 WAR; –1.7 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

There’s only one man able to commiserate with the nightmarish night Chase Wright experienced at Fenway Park in April 2007. That man is Paul Foytack, who Wright matched for the dubious distinction of being the only pitcher in MLB history to give up homers to four consecutive batters. Interestingly enough, one of the batters who took Foytack yard was Tito Francona, the father of the manager whose team victimized Wright. While that was the second of three appearances in Wright’s major league career, Foytack would pitch at a slightly below average level for close to 1500 innings over 11 seasons.

Chet Laabs (1937-1947; 8.7 WAR; –0.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

I’m not a memorabilia collector, but one of my favorite items is a framed 1939 Chet Laabs card. Why would I frame the trading card of a mediocre outfielder who retired 20 years before I was born? It’s a longer story than I can possibly tell here, but let’s just say my father’s vast knowledge of that era enters into it. Laabs enjoyed his best years during WWII, including a 27 HR, 99 RBI campaign in 1942, and was a member of the St. Louis Browns’ only World Series entrant: the 1944 team that lost to the Cardinals in six.

Nick Altrock may have played in five decades, but all of his career value came in four seasons (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Nick Altrock (1898, 1902-1909, 1912-1915, 1918-1919, 1924; 8.6 WAR; –3.5 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

A half century before Minnie Minoso recorded two plate appearances at age 54 in 1980, Nick Altrock was the first five-decade player in MLB history. Altrock’s road to that accomplishment was a little different from Minoso’s, though. A late-blooming but solid pitcher in his late 20s, Altrock’s ability flamed out early due to injury and possibly his lack of seriousness. The quality that allowed him to remain in the majors for so many years was his comic ability, as he entertained fans, distracted opposing players and occasionally took the mound or pinch hit into his 50s.

Pete Incaviglia (1986-1994, 1997-1998; 8.5 WAR; –4.9 WAA)

by Adam Darowski

There aren’t many home run records from 1985 that have not fallen. Pete Incaviglia, however, still holds the NCAA single season (48) and career (100) home run records established during his three years at Oklahoma State University. Baseball America named him the Collegiate Player of the Century. Inky was drafted by Montreal and immediately traded to Texas (leading to the Pete Incaviglia Rule), giving him a chance to skip the minors. Inky bashed 124 home runs in his five years with Texas—but also whiffed 788 times. His most valuable season came in 1993 with the NL Champion Philadelphia Phillies.

Carlos May (1968-1977; 8.1 WAR; –6.1 WAA)

by Dan McCloskey

There were several reasons why Carlos May was best suited to be a DH, but when he lost his right thumb while on Marines reserve duty in 1969, it had to adversely affect his throwing ability. Unfortunately, the DH rule didn’t exist until a few years later, and realistically the injury likely affected his batting as well, but he was still a pretty good hitter and a pretty bad fielder for his career. May’s real claim to fame? He was born on May 17 and wore #17, making him the only player ever to wear his birthday on his uniform.

Glenallen Hill (1989-2001; 8.1 WAR; –3.3 WAA)

by Stacey Gotsulias

Glenallen Hill was built like a brick shithouse. I can say this because he bumped into me on a dance floor in New York City and sent me flying about three feet. It was the night the New York Yankees beat the New York Mets in the 2000 World Series, which earned Hill his only championship ring. He spent time with eight clubs during his 13-year career. He finished his serviceable career with .271/.321/.482/.804 and 8.1 WAR.

Thanks

Thanks to Dan McCloskey for his great idea (and letting me take it over). Thanks to Andy for welcoming me to the High Heat team, allowing me to post it here. Thanks to the wonderful writers to contributed. And thanks for reading!

really enjoying your contributions, adam. when can we expect the “hall of ‘how did they last so long in the majors?'”

You’re probably joking, but I wouldn’t be surprised if Adam’s up for such an idea.

I almost want my role at High Heat Stats to be “guy who writes 100 word capsules about players who fit a certain criteria.” I have other partial drafts of similar ideas that never felt like they had a home.

Catcher for that team: Jamie Quirk. 18 years. Career WAR -0.1. Career WAA -7.7. I guess it pays to be a left handed hitting catcher.

Is it just me, or does Nick Altrock look a little like a tougher version of Don Knotts?

Todd Hundley (1990-2003; 9.3 WAR; -2.2 WAA)

by Bryan Grosnick

Todd Hundley was both catcher and prolific power hitter, and that alone makes him worth remembrance. Hundley held the single-season HR record for a catcher for a few years (41, in 1996), and still stands at 17th all time in HR by a catcher. He was also a remarkable defensive catcher, so long as the remark is “Boy, that guy’s pretty awful.” But to me, Hundley’s greatest achievement was hitting a homer on Opening Day for four consecutive seasons, from 1994 through 1997. He symbolized each New York Mets season: exciting, hopeful, and ultimately flawed enough to escape true greatness.

Yogi Berra also hit HRs on 4 consecutive Opening Days, from 1955 to 1958.

Thanks for your contribution, Bryan! Hundley has always been fascinating. His dad, FWIW, holds the single season record for games caught (160).

Lou Piniella (1964, 1968-1984; 9.3 WAR, -9.7 WAA)

Lou Piniella spent most of his career as a corner outfielder and DH for the Royals and Yankees. Despite a career .291 average, he didn’t walk a lot or hit a lot of home runs, and he racked up a dWAR of -13.3. Still, when I think of Lou as a player, I think of the 1978 one-game playoff when he held a Boston batter to a single on one hop despite being blinded by the sun, saving at least one run. If you type “Lou Piniella” into the BBRef search bar, it will redirect to you his manager page – that’s where his real value lies.

Nice job. Piniella was on my list of 15 to take on for this project, but when I cut it to 10, I left him off.

Great post! One question though…since WAA isn’t in the Play Index, how the heck did you pull the names?

The daily WAR spreadsheets have WAA. And I’ve played with those A LOT. I’ve got my own now that I’ve run a billion functions on.

Tito Francona lost the 1959 AL batting title in 1959 due to a rule change. Prior to that year the BA qualifying requirement was 400 AB but was changed to 502 PA starting with the 1959 season. Francona finished the season with a .363 BA, 10 points ahead of the leader Harvey Kuenn, but with 399 AB and 443 PA. With two games left to go in the season he had 398 AB and could have easily met the old 400 AB requirement.

Correction: The qualifying PA in 1959 was 477, not 502. They were on the 154 game schedule in 1959.

Kind of like how the Blue Jays would have been AL champions in 1985 if the LCS hadn’t been extended that year to best of 7.

This drove me absolutely crazy at the time, Richard. He’d be at the top of those long Sunday lists, ordered by BA, and I was under the impression 400 AB was the criterion. I couldn’t figure out why he wasn’t played a little more at the end – I’d open the paper and start groaning because I had not yet been taught to curse properly. Don’t really know why I was so upset, because I really liked Kuenn. (When I found out the reason, the randomness of 477 made it all seem worthwhile.)

What a spectacular post this is!

epm:

You must be another old timer. I remember wondering why he didn’t play more, too.

Francona, I think, was viewed as a defensive liability, and with Minoso in left and Colavito in right, he could only be platooned with Piersall’s great glove in center or Vic Power’s finesse at first. Francona barely played against left handed pitching, and his stats that season, when he did, show a great falling off from what he was doing to righties—as was the case the following year when he played full-time.

Dan Petry

by Brandon Robetoy

Petry and Jack Morris formed an effective duo at the top of the Tigers’ rotation in the 1980’s. “Peaches” debuted as a 20 year-old in 1979 and had his best years from ’82-’85, over which he averaged 17 wins with a 116 ERA+. He accumulated 17.6 WAR through age 26 but injuries derailed his career path and he struggled for three other franchises until ’91. He finished with 14.9 WAR and -0.9 WAA. In 13 seasons Petry posted a 125-104 record with a 102 ERA+ and is remembered as a member of the Tigers’ World Series team in ’84.

Nice! Out of curiosity, I checked Jack Morris’ WAA. 9.7!

Bert Blyleven had 52.4.

MORE LIKE bLOLeven, AMIRITE?

That really says a lot when you compare Morris / Blyleven by WAA. This coming from a lad who grew up watching the Tigers in the 80’s and patterned my little league pitching motion after his. I’ve always like him but never felt while I was watching him with Detroit that he was a future HOF’er.

WAA is probably the most compelling stat I’ve seen to back up Morris NOT making the HOF.

Hod (Horace Hills) Ford:

Who? Exactly. A college educated (Tufts) man, played primarily 2B/SS for the Braves and Reds in the 1920s. All field, no hit – think poor man’s Rey Sanchez. He managed to get two points in the 1928 NL MVP ballot, though his OPS+ of 58 may be the lowest ever for any non-pitcher in a year in which an MVP vote was received. But 1928 was his best season by WAR standards thanks to his glovework in the short field. Played as many games in his career as HOFer Roger Bresnahan. Has more career dWAR than Roberto Clemente (12.1 to 12.0).

Many old favorites on your list. Among them:

Jody Reed- If I recall correctly, Bill James original Win Shares ranks him as a remarkable defensive second baseman but dWAR sees him mostly as pretty good. My memory of him leans more to the latter.

Brad Ausmus- On the other hand- as outstanding a catcher as dWAR shows Ausmus to be- my memories of him are that he was even better than his reputation. I suspect my views in his case are probably slightly distorted.

Rob Deer- Oh man, I LOVE Rob Deer

Everett Scott- I played in a StratOMatic league where we drafted a team in 1920 and then started playing every year from that point forward while keeping that same team as your base and adding and subtracting players as they came into the league or retired or what have you. In the initial, rather mammoth draft my theory of going with whoever I thought was the best available picks early meant my 1st, 3rd and 4th picks wound up being pitchers so in later picks I went with a eye towards building a strong up the middle defense behind them. That, coupled with a real scarcity of quality shortstops in the 1920’s, meant the I picked Scott in the 8th or 9th round. I didn’t win the league in any of those early years but I was consistently in the first division and in the pennant chase a couple of times.

Tony Clark- Even in his best seasons, I always thought that we were just scratching the surface and that next year he would put up some eye popping numbers.

I see we’re kinda on the same page. 🙂 I took Reed, Ausmus, Deer, AND Scott. Very interesting players, all.

There were SO many other players I wanted to cover.

Steve Sparks (1995-1996, 1998-2004; 8.4 WAR; -2-4 WAA)

Steve Sparks had the quintessential knuckleballer’s career- a late start in the bigs, 3 good seasons with 3 different teams (accounting for 9.9 WAR, more than his career total), and a peak at age 35. Drafted in 1987, Sparks didn’t make it to the majors until 1995. He almost made the Brewers in 1994, but injured his shoulder attempting to tear a phone book in half. Sparks had decent control for a sub-60-mph knuckle pitcher, and led the league in complete games with eight in 2001 – the only year in which he won more than nine games.

Larry Herndon 1974, 1976-1988

-2.1 WAA, 13.3 WAR)

By Brandon Robetoy

Herndon was a OF/DH for the Cardinals, Giants, and later the Tigers wherevhe enjoyed his finest years. In seven years in Motown he slugged .436 after slugging .373 in the seven years prior. In 1982 he hit four HR in four consecutive at bats. His best years were in ’82 and ’83 when he posted WAR of 3.4 and 3.7, hitting 23 and 20 HRs while batting around .300.

Herndon won a World Series with Detroit in ’84 and his HR was the deciding run in game #162 in 1987 against Toronto to clinch the AL East.

Horace Clarke (1965-1974; 13.4 WAR, -2.0 WAA)

Horace Meredith Clarke is remembered by some as the poster child for the mediocre – and sometimes downright hapless – Yankees teams of the late-’60s and early-’70s. While he was no Joe Gordon or Robinson Cano, that assessment may be a bit unfair. Clarke was a decent contact hitter (career .256 BA) in a low-offense era. He was also one of the best defenders of his time, leading the league 21 times in several defensive categories between 1967 and 1972 and finishing with a career dWAR of 6.0. After nine-and-a-half years in New York, he switched coastlines to finish his career with the Padres in 1974.

Those Yankee teams were a few years before my time, but I do remember people referring to the dark days of Horace Clarke. I was surprised when I looked him up to see he really wasn’t that bad. I guess he ended up absorbing the blame for medice teams because he was mediocre. Not sure. Be interested to hear the perspective of anyone who watched him play. Not on him as a player, but why he became the poster child for those teams.

I remember my Yankee friends and me saying that as long as Clarke was a Yankee they would never win a championship. If you check his stats his lifetime OPS+ was only 83, and exceeded 100 in only two seasons. His RBI totals were anemic even for that time period. And that 1968 season with 9 XBH in 579 AB was unforgettable.

Yes, those words get to the core of my point. He was mediocre, but he unto himself was not the problem. He rated positive on defense nearly every year of his career, he even posted fWARs of 3.8 and 4.8 in two of his seasons. He had some speed. Seemed to have some ability to work the count. It was not a period of Robinson Cano, Ian Kinsler, Jeff Kent-line sluggers at second. Carew did come up shortly after Clarke, but that’s not a proper comparison. Teams have won World Series titles with lesser beings.

It’s the question of why did Horace Clarke become the name associated with those teams. Maybe it’s because he had some longevity and he appeared exactly at the collapse post 1964, so he became the symbol. Other players, like Murcer, Munson and White, were good players, and the rest of the team was filled with short timers who never stuck around long enough to be identfied as the problem. In essense, maybe he became the poster child because he was good enough to stick around, but not good enough to be liked.

It’s really not fair in that sense. I could build a very good team around a player like Clarke for a four or five year period.

Horace Clark was bad because he wasn’t particularly good, and his timing was terrible. The Yankees had just won 14 pennants in 16 years, and, then it all evaporated overnight. At every position, the great players of the late 50s/early 60s aged or injured out, and were replaced by inferior substitutes who looked like they might be good, but fizzled. The farm system stopped producing, the Yankees were bringing in other team’s retreads, and they made bad trades. I disagree with the premise that you could build a very good team around a Clark for four or five years. A very good team could have a Clarke at second, like the Yankees did fine with Bucky Dent from 77-81, but they were competent position-fillers, not serious contributors. It’s possible that the Phillies are having their own 1965 Yankee moment, and they will be bad for the next few years. Jack Wilson reminds me of Clarke.

But Horace Clarke was one of the few that didn’t replace a better player. He replaced the overrated Bobby Richardson who benefitted from the halo effect of playing on great teams. They were remarkably similar players but Clarke beats him in defensive and offensive WAR and OPS+.

MikeD: I thought you made a good point about Clarke’s longevity being the reason for making him the whipping boy.

Howard @ #52:

To complete the regression backwards, Richardson more or less replaced Billy Martin in the Yankee lineup, and Martin as a player was on a par with his successors. Martin and Richardson both played well in the World Series. Martin was probably the WS MVP in 1953 before the award was established, and Richardson won it in 1960, despite the Yankee loss to Pittsburgh. Clarke was denied the chance.

One of the strange things about Yankee dominance 1949-1964 is their relative weakness at 2B the whole time.

Reply to #88.

nsb: I think it is a bit of an overstatement to say that the Yankees were relatively weak at 2B for the entire 1949-1964 period. I ran a PI search by OPS+ and found that in 6 of those 16 seasons a Yankee 2B finished in the top 3 in that category 6 times (McDougald with 3, Richardson with 2 and Martin with 1). And yes, there were a few seasons in which they were really weak.

Whatever weaknesses the Yankees had at 2B they more than made up behind the plate.

@52, Howard. Overrated or not by modern metrics, Bobby Richardson won five straight GG, was an All Star seven times, and got MVP votes in six different years (including 2nd in 1962). His contemporaries saw something in him.

RC:

McDougald, of course, I didn’t mention. How dare you detract from my neat linear argument by bringing in facts.

But McDougald was one of those rare fielders who played well anyplace and hit well, too. I only see him as the regular 2nd baseman two years, really. The third he was doing utility work, as he often did, with more games at second than third while Martin was in the service, and Andy Carey new at third.

If Adam—or Andy or Phil (Phil-in-the-blank)—wants to generate another post that generates lots of interest, he couldn’t do much better than finding some stats tracking players like Gil McD, who are barely recognized now, but who had good to great stats and were underrated in their time.

“There are three men who made Casey Stengel a genius—Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle, and Gil McDougald.”—Bill James.

I think Case was a genius regardless, but the assignments he gave McDougald show it as much as anything.

@61, RC, thanks and yes, as I was writing it out it did seem to make sense. In Horace Clark’s case, familiarity apparently did breed contempt. As I noted, Clarke’s Yankee career ended a couple years before I was heavily into baseball so my opinion of him is not personal, but when I talk to Yankee fans even today who do remember Clarke, they seem to bristle. Reminds of bad times, I guess. I try pointing out that those bad times had more to do with CBS ownership (almost all bad times of any length for teams are driven by bad ownership/management), but they’ll have none of it!

@51, Mile L, yes, that was my point. A very good team could be built around Clarke. He wouldn’t be a negative, but he’s also not going to carry the team, and in those days, teams really weren’t putting 2B’man out there who were Chase Utley and Robinson Cano types. In fact, I did a quick look at many of Clarke’s peers, and he would rank in the top half during his prime years. Perhaps the backend of the top half, but top half none-the-less.

Get out our magical time machine, and transport the start of Billy Martin’s career to 1965, while transporting Horace Clarke back to 1951. Clarke would be no doubt positively remembered as being a member and a contributor to those great Yankee teams, while the dark days (Yankee-wise) of the mid-60s to early 70s might be known as the Billy Martin years.

As with many things in life, timing is everything!

@52, Mike L…It isn’t modern metrics that overrate Bobby Richardson. IMO the modern metrics rate him properly. It’s those that kept giving him the MVP votes you mentioned that overrated him. The seven all-star appearances are as much a result of the low caliber of contemporary 2Bs in the AL as of Richardson being overrated. Gold Gloves?..Meh. That “something” his contemporaries saw in him was mostly that he played for great teams.

Just my opinion.

Howard @122, I have to disagree. Contemporary evaluations have to count for something. This isn’t quantum physics, and people need their eyes as validation. Dismissing the sensory entirely diminishes the power of the new stats. Even Bill James uses awards as part of his “Hall of Fame Monitor” math.

I’m with you on this one. While I accept the possibility that Richardson might have been overrated defensively, I also accept the possibility he was as good as advertised, or I accept the possibility that he was even better. There is nothing that can be pointed to with a strong degree of credibilty since it’s an attempt to assign defensive metrics on plays and fielders 50 years back.

There are legit questions about modern defensive metrics, including ones that visually score every play. While I applaud the attempts to do this on generations past, I give it about as much attention as the amoung of time it took me to write this post.

Yes, visually scouting still rules, and that’s coming from someone like me who is a longtime saberist. The data needs to be used in conjunction with scouting as a way to enhance talent evaluation. Richardson played long before this came into play so all we have really all we have is the talent evaluation. The numbers don’t tell us much.

Bobby Richardson could easily have a post in this series. (WAR 6.5, WAA -9.0) His offense was overrated because he had a decent BA with no power and no walks. (.266/.299/.335) Power was not expected from 2B and OBA was ignored. His best offensive year he led the league in PA, AB, hits and still could not score 100 runs batting in front of Mantle, Maris and the other Yankee sluggers. He was a good fielder and maybe deserved some of his Golden Gloves, but knowing how often those awards are given to someone who is not the best, (yes, I’m looking at you, Mr. Jeter.), I put very little weight on his success their.

Ok, I’m taking one more shot (and you all gave me a great idea for a political blog post-thanks again for one of the most stimulating forums around.) There’s an interesting old Isaac Asimov short story called “The Red Queen’s Race” in which an unhinged nuclear scientist sends back in time to Hellenic Greece a modern chemistry text, translated into ancient language. The modern world waits for the impact, figuring that the course of history must change. But it doesn’t, in part because the context to support those discoveries was not in place. You also use “Red Queen’s Race” to describe a conflict situation where any absolute advances are equal on all sides such that the relative advantages stay constant despite significant changes from the initial state. So, with that out, let me suggest the following about Bobby Richardson and those like him who were held in contemporary esteem even though we might disparage them in hindsight. Richardson was doing the things that were valued by his team, and baseball in general, at that time. What we don’t know is whether he was capable of doing the things we currently value, but putting the ball in play, a decent batting average, sacrificing or otherwise moving the runner up, was valued then. Here’s an interesting stat about Richardson-in 5783 Plate Appearances, he struck out only 243 times. I’m not claiming Richardson was a great player, but to dismiss all contemporary judgements of him, which were based on what people cared about and expected in his time, is unreasonable.

kds summarized my thoughts pretty well in post #127.

@129, Mike L: just as you’re not claiming Richardson was a great player I am not claiming he was a terrible player. Just that he was overrated.

Tom Brookens — Brookens had a long career with the Tigers despite regularly leading the league in errors and mediocre offensive ability. Every year, there was a new plan at third base (Lou Whitaker will move to make room for Chris Pittaro, Torey Lovullo, Jim Walewander and, of course, the genuine talent of Howard Johnson). And every year, Brookens would wind up playing more than 100 games, somehow also taking time away from Whitaker and Trammell at Short and Second. Well liked in Detroit, and now a perfectly good first-base coach, Brookens always found a way to play regularly despite having the lowest OPS+ of any Tiger regular in 1982, 83, 85 and 87, escaping in 84 and 86 only because he wasn’t a regular. Truly an amazing run.

Sorry. He also had the lowest OPS+ of any regular in 81.

If memory serves correctly, Brookens was the inspiration for an essay by Bill James on how the Tigers had cost themselves several pennants over the years by continually using mediocre 3rd baseman. It was in one of the Abstracts so unfortunately not available online.

While he was error prone, Brookens did finish with 6.7 dWAR. This included 0.8 and 1.4 the two years he led the AL in errors.

I agree though that the Tigers suffered because they never found a suitable replacement for Brookens.

It’s too bad HoJo didn’t blossom sooner. After the influx of talent during the late 70s the Tigers failed miserably in player development.

I don’t recall Brookens “stealing” time from Tram and Lou though. Granted Brookens got way too much playing time, but that was more of a function of Trammell’s nagging injuries and Whitaker getting an occasional day off versus lefties.

“It’s too bad HoJo didn’t blossom sooner.” It’s true that HoJo was just OK in ’84, but I still can’t agree with this assessment. Sparky just didn’t like HoJo and buried him whenever he could. It’s not hard to imagine that Sparky’s treatment delayed HoJo’s breakout.

HoJo’s offensive potential was obvious. He was the #12 pick in ’79, and by ’82 he was in AAA with a monster year — .317/.962 plus 35 SB. He hit very well in his 2nd call-up to Detroit that year, .352/.895 in 41 games. But he got off to a slow start in ’83, .212 in just 66 ABs, and then got hurt, missing pretty much the rest of the year.

And Sparky wasn’t in a patient mood in ’83-’84. He had been hired in ’79 and had basically promised a title within 5 years. Time was running out.

Even though the limitations of Brookens were already clear by ’84, Sparky just wouldn’t commit to HoJo, giving 4 others at least 14 starts at the hot corner. And even though HoJo did get most of the starts at 3B that year, in the playoffs Sparky basically benched him for the no-hit, unproven C/3B Marty Castillo.

I think Sparky’s conception of a 3B was warped by his early years with the Reds: Tony Perez had a huge year in ’70, Sparky’s first season, and a good year in ’71, but for a variety of reasons they switched him to 1B in ’72 and that triggered a 3-year stretch of Sparky being frustrated by 3Bs who either couldn’t hit (Dennis Menke, John Vukovich) or couldn’t field (Dan Driessen), until Sparky finally pulled Pete Rose in from the outfield to plug the gap in May ’75. Rose was no glove man at 3B, but he hit .300, and, well, he was Pete Rose; he was one of Sparky’s guys.

I don’t think Sparky was ever really satisfied with a 3B who wasn’t one of his original stars.

Broookens drove me crazy. It was impossible not to like the guy and it wasn’t his fault they made him a starter instead of the utility player in a part time roll like he should have been. And it wasn’t like the Tigers weren’t trying to find a replacement for him either. But the sad truth is that all by himself, Brookens probably cost the Tigers at least one and maybe a second playoff appearance. The most frustrating part is that in a limited utility/pinch hitting role Brookens could have been mostly a reasonably valuable contributor on those teams.

Hartvig — I picked him for exactly that reason (I had a feeling he’d be on the list once I saw the title of the post). I also remember Bill James’ article.

Looking at the numbers, however, it seems a bit unfair. Johnson didn’t become truly valuable until 87 (when the Tigers won the division anyway), so it seems he would have helped most in 88. Otherwise, it isn’t clear that they ever were close enough to win merely by upgrading 3rd base.

Still, had they kept HoJo, that 87 team would have been a beast, and they probably would have finished first in 88 as well.

It is amazing, however, that the team never found a way to upgrade their lowest OPS+ player for 7 years.

I’ve never actually seen the James article that has been mentioned a couple of times. And yes, to be fair, in order to make the LCS in ’83 or 86 they would have either needed to Johnson playing at his absolute peak of his career level or have somehow managed to land Wade Boggs to replace him. So blaming either of those years entirely on Bergman isn’t really fair.

But tough. It’s my memory and I’m stickin’ to it.

I love that you substituted Bergman for Brookens. Sparky, for all his strengths, had certain guys he used way too often, and it cost the team.

My memory is the same as yours, fair or not. Of course, I remember that John Wockenfuss always popped out in any “clutch” situation and the records don’t reflect that either.

I’ve got two old BJ Abstracts-from 86 and 88, each one covering the season before. James is critical of Brookens in each (his out making abilities and fielding) and makes a point of how the Tigers had great stability among position players-except at third base.

Ralph Garr (1968-1980, 13.0 WAR, -2.6 WAA)

Ralph Garr was among the outstanding contact hitters of the 1970s, a .300 hitter 5 times, 200 hits thrice, and the NL batting champion of 1974. Playing outfield primarily with the Braves and White Sox, Garr’s .307 batting average for 1970-79 ranks 9th. Garr had modest strikeout totals but, unfortunately, even more modest walk numbers, thus placing higher than 10th in runs scored only once, despite batting 1st or 2nd in over 90% of his career PAs. His notable speed did not translate into defensive prowess (-11.3 dWAR), but is reflected in his totals for stolen base (14th in 1970s, 75% success) and triples (twice NL leader, 6th for 1970s).

Jim Lonborg (1965-1979, 11.8 WAR, -0.5 WAA)

Jim Lonborg, a 6’5″ right-hander, won 157 games over 15 seasons, pitching primarily for the Red Sox and Phillies. His best season was 1967 as he led the AL in wins and strikeouts to claim his only Cy Young award. Lonborg prevailed over former CYA winner Dean Chance of the Twins in a memorable winner-take-all game for the AL pennant. In the World Series, Lonborg won twice before falling to Bob Gibson and the Cardinals on two days rest in game 7. Lonborg suffered from a loss of form after 1967, possibly due to his high workload that season. In his later years, he was effective in the Phillies rotation in in their return to the post-season for the first time in a generation.

Doug – Lonborg was in a ski accident after the ’67 season. He damaged knee ligaments and was in a waist high cast for 6 weeks. He missed the beginning of the ’68 season and when he returned he altered his pitching motion to compensate for his weakened knee. Unfortunately the new motion placed too much stress on his shoulder and led to arm problems. For a while the owners adopted what was known as the “Lonborg Rule” – players injured outside the ballpark could be placed on the temporarily inactive list and not paid.

BTW, after his baseball career was over, Lonborg went back to school and became a dentist.

I assume that the claim that Carlos May was the only player to ever wear his birthday on his uniform was some sort of joke that I don’t understand?

Carlos May was born on May 17th. With the number 17 on the back of his jersey he also had his last name “May” directly over his 17.

I’m not sure any other players have been able to duplicate this odd distinction.

Seems really unlikely.

Phil Marchildon was born in October.

Darrel May was born in June.

Dave May was born in December.

Derrick May was born in June.

Jakie May was born in November.

Jerry May was born in December.

Lee May was born in March.

Lucas May was born in October.

Milt May was born in August.

Pinky May was born in December.

Rudy May was born in July.

Scott May was born in November.

Lee Maye was born in December.

June Greene was born June 25, 1899, but of course his uniform would have said Greene, except that I think he played before he would have worn a number anyway.

Don August was born in July.

Carlos’ brother, Lee May, also qualifies for The Hall of Clearly Above Replacement but Below Average. Both Mays were good hitters but atrocious defensively.

Carlos’ career got off to the better start. He reached the majors at age 20 and posted a 137 OPS+ at age 21. But his career petered out and his last year in the majors was at age 29. On the other hand, Lee was 22 when he reached the majors and didn’t have his first decent season till he was 25, posting a 135 OPS+. Despite the slower start to his career, Lee under up playing nearly twice as many games as his brother and finally retired at age 39.

Lee’s son – Lee May Jr. – was later a first round pick of the Mets and posted some of the worst minor league stats I’ve seen (he never made the majors). In over 2,000 PAs, he batted .221, had a .282 OBP and slugged .290. Which wouldn’t be too bad if he were a middle infielder. Unfortunately he was an outfielder.

P Bill Voiselle, who was raised in a town called Ninety-Six, NC, wore #96 on his uniform.

Now I see that Voiselle is on the list.

Ninety six is in South Carolina, not NC. I recently worked with a pharmacy student from there while she was on rotation in my part of SC.

Thanks for the correction but Voiselle’s BR homepage has him listed as attending Ninety-Six HS in NC.

Thanks. Do I feel dumb. I was only thinking of the number.

Looks like Brandon and Andy have basically answered this question, but when I read this tidbit in a few different places, I double-checked myself by searching baseball-reference for players whose last names are also months. As Andy points out, there are a lot of Mays, but Carlos is the only one born in May. So, not only is he the only player to wear his birthday on his uniform, he’s the only player who could have worn his birthday on his uniform.

Bret Boone (1992-2005, 19.5 WAR, -1.3 WAA)

Ray begat Bob. Bob begat two players, Bret and Aaron “Bleeping”. Both of Bob’s progeny are in the HOCARBNQA. Bret was a 2x Silver Slugger winner, 3x All-Star, and 4x Gold Glove winner. Finished 3rd in 2001 AL MVP voting when the second sacker paced the junior circuit in RBI for a Mariners team that won 116 games. From 2001-2003 accumulated 17.9 WAR and 11.7 WAA making his inclusion on this list … impressive. Career went downhill in 2004 and fell off a cliff in 2005 – no one is quite sure why. Received a Hall of Fame vote in 2011.

Boone has a really bizarre career trajectory.

From ages 23-31: -7.8 WAA, 3.7 WAR (7.2 oWAR, -1.1 dWAR)

32-34: 11.7 WAA, 17.9 WAR (17.1 oWAR, 2.1 dWAR)

35-36: -5.2 WAA, -2.1 WAR (1.0 oWAR, -2.5 dWAR)

I have no idea how to explain this.

Are you being sarcastic? I don’t see a smiley face.

Boone was widely suspected of taking PEDs and he was named in Canseco’s book. That being said, Boone always denied using and the story Canseco told didn’t check out.

I’m not. I’m actually kinda baffled by this. His offensive numbers went way up during that period, but that seems to be attributable to being both a better contact hitter and a better power hitter. Plus, his power numbers were already going up before then, except for his ’00 year, which of course was played in the Giant Q. Finally, his defensive statistics also spiked around this time.

Maybe he was using the eight-letter-word drugs, but the last I checked they don’t help you make better contact or play better in the field. In fact, if he was, I would guess he started doing them at age 29, when he started clobbering 20-plus home runs after only hitting about 12 a year before that.

I’m sure he’s remembered fondly in Seattle, but whenever I think of Boone I think of him swinging and missing at a pitch in the Home Run Derby.

What a fun project. Great work, guys.

Joe Vosmik:

Joe Vosmik and the Indians thought they could seal the batting title by sitting him both games of a double header on the last day of the 1935 season even though his lead was only .349-.345 over Buddy Myer. When they got word that Myer was having a big day Vosmik was put in for one AB in the first game and all of the second game. After going 1-4 his BA fell to .348 and Myer, going 4-5, won the title at .349. As it turned out if Vosmik had continued to sit he would have shared the title with Myer as both would have finished with 215 hits in 615 ABs. Good for Myer and it serves Vosmik right. Sitting on a lead like that is cheap.

Chambliss is an interesting player. In many ways, he illustrates one of the hitting styles that overtook baseball after the collapse of hitting and the Year of the Pitcher in 1968. Hitting throughout the 1970s was depressed by historical standards and Chambliss came of age during that time, where hit-to-contact was in form, players tried to avoid strikeouts, and line-drive gap hitters were in fashion to take advantage of bigger ballparks.

Chambliss was cast as the big, lumbering power-hitter at first, yet his hitting style was anything but. His bat was a bit slow to start, and he had a very closed stance with his number seemingly facing the pitcher all the time. As such, he never really could get around on balls to pull them and take advantage of the shorter RF at Yankee Stadium. He was more of a line drive, straight away, contact hitter.

I’m quite sure if Chambliss’ career began twenty years later, or even ten, he would have had a straight-up stance, if not even slightly open, to compensate some for his bat speed, and to pull the ball more. At his peak, he probably would have been more of a 30-HR threat, but his BA would have suffered, I’m guessing.

I just spent way too much time reading this post. Awesome and fun. And the comments! If it weren’t nearly 5 in the morning I’d be tempted to put in 100 words about someone…

Yup, that’s about the size of it! Great stuff.

Great idea and good write-ups! However, Mike Piazza was the 1993 NL ROY, not Jeff Conine.

These comments are exactly what I was hoping for when we conceived the post. Keep ’em coming!

Surprised nobody has written about Ozzie Guillen. 🙂

Adam, great to have you on the site. I didn’t comment on your first article about WAA and WAR because I have similar reservations as JA about WAA’s use, and I can’t argue as eloquently as he does.

Still, I do plan to do a short Mark Lemke piece for this thread, but it’s going to have to wait til tonight.

Sean Casey:

The Mayor had 3 pretty good years in 99,00 and 04.

with WAR of 3.8, 3.2 and 4.1 respectively, he

achieved almost 80% of his career total (14.3)

in those 3 seasons. His career high of 25 HR in

a season, stands out as quite low in a period of

slugging first baseman. His .302 career average

is accompanied by an OPS+ of 109.

One of the most popular players in franchise history,

Casey left the Reds after the 05 Season to join the

Pirates. Casey was acquired on the trading deadline

in 06 by Detroit. Detroit eventually reached the

World Series which they lost in 5 games.

No fault of Casey’s as he went .529/.556/1.000/1.556 “at the bat”.

A few words about George Case. This speedster had an 11 year career from 1937-1947. I don’t know why he never entered military service. He is reputed to have been the fastest runner in baseball during his playing time. His specialty was stealing bases, leading the AL in SB 6 times. He was the first to lead the league for 5 consecutive years. If it had not been for George Stirnweiss his streak would have been 8 years. In 1946 Bill Veeck staged a race between Case and Jesse Owens as one of his promotional stunts. Owens won.

Garrett Anderson was a lot of things over the course of his career – a World Champion in ’02, an All-Star MVP in ’03, a Home Run Derby Champ (also in ’03), a doubles machine (330 from 1996-2003). He was never a patient hitter, though – his career high in walks was 38, in 2006. That, combined with his lack of range in left field, left him a below-replacement level player over the last 6 years of his career, despite his decent peak. Ah, well – we’ll always have Chicago, Garrett.

If there ever is a Mount Rushmore to “Players clearly above replacement but not quite average” I would put Garrett up there along side Joe Carter and Bill Buckner. I haven’t given it enough thought yet to decide who the fourth might be but unlike the previous Mt.Rushmore’s we have been voting on and for reasons I cannot explain I tend to lean strongly towards players who have been active in my lifetime.

On second thought, I guess it’s not their fault that they’ve been over-hyped and over-rated so maybe we should spare them that particular form of immortality.

In doing research for this project, I realized that the pitching version of Joe Carter is probably Lew Burdette. I mean, he even got 24% of the Hall of Fame vote! And he was below average! But he won games!

I remember reading somewhere that it was viewed he played poorly in his latter years & “pitched his way out of the HOF.” it’s possible his 3 wins in the ’57 WS would have helped a lot with his candidacy like Larsen’s perfect game did & Vandermeer’s no-hitters did.

What about Hal Chase? I remember hearing discussion, a long time ago, that he might have made the Hall of Fame had he not been kicked out of baseball.

Richie Sexson

I remember in spring training of 2004, Tim Kurkjian said that the 500 homer club would lose its legendary status when Richie Sexson got there in a few years. At the time it was a bold, but not unthinkable, prediction for the young slugger – he’d just turned 29, and had blasted 119 of his 191 career homers in the last 3 years. Even after he missed most of ’04 due to injury it seemed doable for Richie, as he hit 73 more homers between ’05 and ’06. Those injuries caught up to him hard in ’07, though, and he never got his swing back over those last two miserable years of his career – costing him his chance at any immortality besides this sad one.

When I say that sabermetrics ruined my childhood, I’m talking about Vinny Castilla. I was scared to death of my team facing him in that Rockies lineup from 1996-1998, when he hit .309/.354/.562 with 126 homers. 1999 was the year where it all went wrong, though – his batting average dipped a little, and suddenly 33 homers and 102 RBIs was barely replacement level. By the time he landed with my Braves in 2002 I had realized how inflated his (thin-air-assisted) power numbers had made his value seem, and then he went and proved it with a .616 OPS that first season in Atlanta. By the time he led the league in RBIs back with Colorado in 2004, I knew which stats were bunk.

The HoF voting for Castilla in 2012 would ALMOST be enough to give someone hope that the sportswriters were finally starting to catch on until you realize that just two years prior that Robin Ventura- who was three times the player Castilla was- managed get exactly 1 more vote than Castilla.

Now that Santo’s in the Hall, does Ventura have any competition for the starting job at third on the Hall of Very Good team? I mean, until Rolen retires it seems like he’s got it clinched.

Answering my own question: Ron Cey. But I’d still give it to Ventura’s glove.

So many good candidates for that position. Deacon White is my #1, though he spent a lot of time behind the plate, too.

Others include Ken Boyer, Graig Nettles, Sal Bando, Buddy Bell, and Darrell Evans. Ventura and Cey are also up there.

I always forget Evans played third – he was one of my dad’s favorite players and so I’m supposed to defer to him whenever possible. How are there not more third basemen in the Hall? It’s not for lack of talent at the position!

There were a lot of third basemen added to my Hall of wWAR.

White

Boyer

Nettles

Bando

Bell

Ned Williamson

Evans

Were all deemed Hall-worthy while

Kell

Traynor

Lindstrom

were booted.

I personally would put Ventura, Cey & Matt Williams in the bottom half of a group with the 5 modern era players that Adam mentions in 91. I’m uncertain as to where I would put White or Williamson in that bunch without giving the whole issue a lot more thought although it’s pretty indisputable that those 2 along with John McGraw were the best at their position prior to the arrival of Jimmy Collins and Home Run Baker.

White is the one that I’m absolutely 100% sure should be in the Hall of Fame. The other third basemen are tricky. It’s almost like you either need to put them all in or none. Honestly, it might be more fair to put all in.

But White is one of my pet cases. Third base and catcher are both underrepresented. He played both. He was a pioneer and could mash (127 OPS+ across 20 seasons).

He compiled over 2000 hits even though the schedule didn’t even expand to 100 games until he was 36.

The player I’d compare him to? Honestly, probably Joe Torre. He caught and played third (and first). He had a 129 OPS+. I also think they both have a lot going for them outside of their playing careers.

For Braves fans, Otis Nixon is beyond reproach. He was the spark plug of the ’91 worst-to-first team with his .372 OBP and 72 steals, and of course he’s the guy who made The Catch in ’92. We’d never mention anything bad about him, like the fact he looked like he was 80 in his mid-20s, or how he had no – I mean absolutely 0 – power, or how his cocaine habit might’ve killed our World Series hopes when he got his ass suspended for the ’91 postseason, or how he’s the only guy to ever end the World Series on a bunt. We’d never talk about those things in Atlanta. We miss him even more than Rafael Belliard.

Pat “The Bat” Burrell was known for two things as a baseball player: his power (he hit 27+ homers 6 times) and his patience at the plate (he walked at least 98 times four straight seasons, and finished with an OBP over 100 points higher than his batting average). He was a huge part of two championship runs – Philly’s in ’08 and Frisco’s in ’10. He was also a black hole defensively, and once defecated on a woman’s floor after having a one night stand with her. Take a picture, Pat – this is what people will remember you for.

Great project, Adam! At least a few of these players have been written up as part of the SABR Bio Project. Do you have any plans to contact the authors of those works and ask for a 100-word extract?

I wasn’t thinking of doing that. I think we’ll keep it in the HHS house. 🙂 I love what folks are coming up with!

Jermaine Dye

There was a time – probably in 1999 or 2000, the two years over which he had a .915 OPS and won a Gold Glove for the Royals – when I wished my Braves hadn’t traded away Jermaine Dye. Looking back, I see that we saved a lot of frustration: Dye was a player who flirted with greatness – most notably winning the 2005 World Series MVP and parlaying that into a huge ’06 that saw him hit .315/1.006 with 44 homers – but whose total lack of defense (-11.4 career dWAR) and inconsistent bat (he posted a 38 OPS+ in 221 ABs in ’03) kept him from ever achieving it.

Aurelio Rodriguez (1967-1983; 11.7 WAR, -9.3 WAA)

Before Alex Rodriguez, there was another A-Rod manning the hot corner in the American League. Unfortunately, Aurelio Rodriguez wasn’t quite as gifted at the plate as Alex is. In fact, he posted a .237/.275/.351 line over 17 seasons – bad for any position, but truly remarkable for a corner infielder. It was his excellent defense (14.4 dWAR), though, that made him a well-above replacement player. However, he earned little recognition for this; overshadowed by other cowhide-eaters like Nettles and Robinson, Rodriguez’ only Gold Glove came as a member of the Tigers in 1976.

If I recall correctly, Aurelio used the same mitt his entire career. By the end, the mitt was a mess, but he still managed to catch the ball with it.

His mitt was called “mano negra” (the black hand). That´s the only time I´ve ever know that a player gives a name to his glove.

Walt Weiss’s career began swimmingly – he won the the 1988 AL RoY, got a ring with the A’s in ’89, and posted a 4 WAR season in 1990. After that, though, he just kind of settled into the mediocrity that defined his career, his lack of power ill-suited for the thin air of Colorado, where he played 4 years. He actually had the best hitting season of his career in 1998 with the Braves, but here in Atlanta we mostly remember him as the guy whose kid got E. coli at Whitewater, which tells you all need to know about him as a ballplayer, probably.

I would have to imagine that that’s not how most ballplayers picture themselves as being remembered…

As with Bret Boone, I’m sure there are places other than Atlanta where Weiss is remembered a little more fondly. Oakland, for example. Though he was decent here in Atlanta, though, the whole Whitewater/E. coli thing was a major story on the local news, and I’m sure most people in the city remember that more than the great diving stop he made in the ’99 NLDS (especially if they were, like me, 12 or 13 when it happened and suddenly not allowed to go to the water park anymore).

I’ll never, ever forget that play by Weiss, Andrew!

Jody Reed was robbed!

Looking at that vote and the stats, it’s really hard to figure out what anyone was thinking. Weiss has the edge in most of the counting stats, but only because he played in 40 more games. I suppose it doesn’t hurt to be the starting shortstop on a 104 win team, though.