Seven teams since 1901 had five players age 30 or under who would amass 50+ career WAR.* But those seven comprise just four distinct clubs. We’ll track the progress of those teams, after the jump.

Teams with Five Players 30 or Younger, Who Would Amass 50+ Career WAR

- Philadelphia Athletics, 1925 through 1928: Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane, Eddie Rommel

- St. Louis Cardinals, 1970: Steve Carlton, Dick Allen, Joe Torre, Jose Cruz, Ted Simmons

- Houston Astros, 1991: Curt Schilling, Jeff Bagwell, Kenny Lofton, Craig Biggio, Luiz Gonzalez

- Atlanta Braves, 1996: Greg Maddux, Chipper Jones, Tom Glavine, John Smoltz, Andruw Jones

1) The A’s of 1925-28 might boast the best group of young talent ever kept intact for a baseball generation. It took a while to mature, but this team would win three straight pennants starting in 1929:

- Lefty Grove, 110 career WAR, age 25-28 in these years (his 1st-4th)

- Jimmie Foxx, 96 WAR, age 17-20 (1st-4th)

- Al Simmons, 69 WAR, age 23-26 (2nd-5th)

- Mickey Cochrane, 52 WAR, age 22-25 (1st-4th)

- Eddie Rommel, 50, age 27-30 (6th-9th)

5-man Totals: 377 career WAR … 17 WAR in 1925 … 20 in ’26 … 18 in ’27 … 24 in ’28

All five were together for 8 seasons, 1925-32.

Three were together for 9 seasons, 1925-33 (Grove, Foxx and Cochrane).

But would the baby ever come? They finished 2nd in 1925, breaking a 10-year lease on the second division, paced by the super-soph Simmons and a balanced rotation topped by Rommel’s 21 wins. The rookie Grove, a minor-league marvel bought for a hundred grand, was injured and unimpressive, mainly in relief. Cochrane hit .331 as a rook, but was raw behind the plate, and the teenage Foxx just watched. They also had Max Bishop (age 25 in his 2nd year, 37 career WAR), Jimmy Dykes (age 28, 35 WAR), Rube Walberg (age 28, 38 WAR), Bing Miller (age 30, 29 WAR), and landed Jack Quinn in midseason (59 career WAR, and still going strong at 41).

Grove found his groove in ’26, his first of nine ERA titles pacing an historic staff (139 team ERA+). But the lineup didn’t gel: Simmons slumped a bit, Cochrane was learning on the job, and Foxx was still a neutral observer. In ’27, old superstars Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins and Zack Wheat came aboard and hit a combined .344, helping build the club’s best record since 1914, but the Yanks ran away from the pack.

By 1928, the “5×50-WAR” class all were stars; this is the only team with five 50-WAR regulars age 30 or under. The A’s led the race on September 8 — then dropped three straight in the Bronx, and never recovered.

But the payoff was worth the wait. From 1929-31, the quartet of Grove, Simmons, Foxx and Cochrane averaged 7 WAR per man per year, and Rommel still was a useful swingman. The A’s averaged a 104-48 mark, copped each pennant without serious threat, and fell a Game 7 short of winning all three World Series.

The 1932 A’s went after an unprecedented 4th straight AL pennant, but stumbled out of the gate. They recovered to finish 94-60, a .610 W% and 4 games above the NL champs — but 13 games behind the Yankees. Once again, Mr. Mack saw the writing on the wall: Success meant bigger salaries, but the Depression had wiped out attendance. Philly’s gate dropped more than half since ’29, with barely 5,000 a game witnessing this great team. The break-up was inevitable.

ATHLETICS SIDEBAR

Nine key A’s stayed together from 1925 through at least ’32, when Rommel retired, and Simmons & Dykes were sold to the ChiSox (along with Mule Haas).

Athletics’ Core, 1925-32

| Player | 1925-32 WAR/pos |

1925-32 WAR/pit |

1925-32 Age |

Career WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lefty Grove | 57.5 | 25-32 | 109.9 | |

| Jimmie Foxx | 36.0 | 17-24 | 96.4 | |

| Al Simmons | 49.4 | 23-30 | 68.7 | |

| Mickey Cochrane | 34.4 | 22-29 | 52.1 | |

| Eddie Rommel | 21.6 | 27-34 | 50.4 | |

| Rube Walberg | 29.6 | 28-35 | 38.3 | |

| Max Bishop | 30.2 | 25-32 | 37.4 | |

| Jimmy Dykes | 21.1 | 28-35 | 35.4 | |

| Bing Miller* | 14.5 | 30-37 | 28.8 |

After 1933, Grove, Bishop and Walberg were parceled off in one deal, Cochrane in another. Miller (*whose term had a one-year sabbatical) was waived after ’34, at age 40. Foxx was the last Beast bartered — in the fall of ’35, after the ashes of Mack’s second dynasty drifted into the cellar. A dozen years passed until the A’s again saw the first division.

The Red Sox bought Grove, Bishop and Wes Ferrell in ’34, and reached .500 for the first time since Ruth. They added Foxx in ’36, and by ’38 had climbed to 2nd place. 1939 was the last great year for Grove and Foxx, and the debut of Ted Williams, all three scoring 6.7 to 7.0 WAR. They had Joe Cronin near his prime, and a young Bobby Doerr just approaching his, but it wasn’t nearly enough to keep the Yankees from a 4th straight championship.

____________________

2) The 1970 Cardinals were the next club with “5×50<=30,” going 76-86 with:

- Steve Carlton, 90 career WAR, age 25 in 1970 (his 6th year)

- Dick Allen, 59 WAR, age 28 (8th year)

- Joe Torre, 58 WAR, age 29 (11th year)

- Jose Cruz, 54 WAR, age 22 (debut cameo)

- Ted Simmons, 50 WAR, age 20 (3rd year, but first as a regular)

5-man Totals: 311 career WAR … 13 WAR in 1970

All five were together just that one year.

Four were together 2 years, 1970-71 (Carlton, Torre, Simmons and Cruz).

Three were together 5 years, 1970-74 (Torre, Simmons and Cruz).

After 1968, their third pennant in five years, the Cards still were in shape to contend for years to come. Bob Gibson would average 18 wins and 7.0 WAR in the coming five years, 3rd in pitcher WAR for that span. Lou Brock stayed a potent leadoff man through ’74 (when he set the season steals mark), averaging .305 BA with 106 runs and 70 SB from ’69-74. Carlton turned 24 after the Series, then earned his second straight All-Star nod. By 1970, the system had produced Simmons, Cruz, Bobby Tolan, Jerry Reuss and Mike Torrez, and by ’74 a second wave of Keith Hernandez, Bake McBride, Jerry Mumphrey, John Denny, Bob Forsch and Jim Bibby. And two big trades got the retooling started, landing Torre and Allen in their primes.

Yet they never really came close throughout the ’70s, finishing the decade with a losing record. What happened?

Mainly, a long string of impatient trades. Chronologically:

— Tolan, a triple-A star at 19, didn’t break through in two half-years by ’68. When Roger Maris retired, they swapped Tolan and reliever Wayne Granger (coming off a sharp rookie year) for Vada Pinson. This was a bust: In the next two years, Pinson’s decline continued, while Tolan finally blossomed in the Pinson mold, averaging .310 BA, 18 HRs, 42 steals and 108 runs. Granger averaged 31 saves and 115 IP with a 2.75 ERA, and the pair helped Cincy to the ’70 pennant. When those two years were up, Pinson had been parlayed, through Jose Cardenal and Ted Kubiak, into the Legend of Joe Grzenda.

— Compounding Granger’s absence, closer Joe Hoerner went in the deal that brought Allen for 1970, and it took five years to fill the gap. From 1970-74, Cards closers averaged 10 saves and 1.5 WAR. They reacquired Granger for ’73, when he was about spent, at the cost of Larry Hisle; the former ROY contender had just regained his footing with a huge year at triple-A, age 25, and would average 4 WAR in the bigs for the next six years.

— The Allen trade also brought in veteran 2B Cookie Rojas, whose bat had waned in recent years after a strong start. Rojas was just insurance for Julian Javier, who’d turn 34 that summer. Indeed, Javier faded quickly starting that very year — but Rojas got just 51 PAs in two months before he was dumped, for minor-league veteran Fred Rico. Rojas revived in Kansas City, with four straight All-Star years.

— Allen had an Allen year in 1970: team-high 34 HRs, 101 RBI and 146 OPS+, with 17 of the team’s 51 home-field HRs, and none of the turmoil that dogged his Philly years. But they still shipped him out, just four days after season’s end. The Dodgers gave ’69 ROY Ted Sizemore, who would replace Javier. At least Sizemore out-WARred Rojas in the next four years (10.3-8.3), but that hardly made him a fair return for Allen, who racked up 14.0 WAR and an MVP in just the next two years. St. Louis ran second in ’71, with 1.3 WAR from Sizemore; meanwhile, Allen had a 151 OPS+ for LA, and Philly’s haul from the original trade showed Hoerner with a 1.97 ERA in 73 IP (2.7 WAR), Tim McCarver with 2.1 WAR, and ROY runner-up Willie Montanez with 30 HRs and 99 RBI.

— Two key pitchers from ’68, Ray Washburn and Nelson Briles, got hurt in the next two years, and were swapped out with little return. Washburn was finished, but Briles bounced back with the Bucs, helping them to ’71 title with a 2-hit shutout in the Series.

— Torrez went 10-4 as a rookie swingman in ’69, and was okay as a 23-year-old soph. Injured in ’71, they swapped him to Montreal for ex-1st-round pick Bob Reynolds. After pitching Reynolds for 7 innings in five weeks, they bundled him and Cardenal for the weak-hitting Kubiak — and three months later, Kubiak begat the 35-year-old Grzenda, who won his only St. Louis decision and then retired. Reynolds became a relief ace with the ’73-74 Orioles, going 14-10 with 16 saves and a 2.25 ERA in 180 IP for those division winners. Torrez won 164 games after leaving St. Louis, and won two complete games in the ’77 Series, including the clincher.

— The big one: After Carlton won 20 in ’71, he wanted more dough, and owner Gussie Busch ordered a trade. Carlton went straight-up for Rick Wise, who at least was a year younger (27-26). Each had five full rotation years at that point:

- Carlton, 74-59, 3.11 ERA, 113 ERA+, 905 Ks, 19.7 WAR.

- Wise, 65-67, 3.56 ERA, 99 ERA+, 620 Ks, 11.2 WAR.

Oops. Wise was good in ’72, his 4.9 WAR about matching Carlton’s prior 3-year average — but it paled against Lefty’s historic outburst. So the next year, Wise was moved along with Bernie Carbo, for Reggie Smith and Ken Tatum. They could have won that one — Smith turned in two fine years — but he started ’76 slowly and was dealt to LA, for Joe Ferguson and two guys who didn’t pan out. Then Ferguson didn’t hit in his half-year, so he was shipped to Houston for a washed-up Larry Dierker and a scrub. Dierker won two games in ’77 and retired, while Carlton won his second CYA for Philly. Ferguson rebounded with a 124 OPS+ from ’77-79, and Smith was a key to LA’s ’77-78 pennants, averaging 30 HRs and .302/.406/.568. By ’78, the Cards had nothing left from any of those deals. And we’re far from done.

— Reuss had a sophomore slump in ’71, but more importantly, Busch didn’t like his facial hair — so off he went to Houston for Scipio Spinks. Scipio started well in ’72, but got hurt on July 4 and was basically done. Reuss had his ups and downs, but won almost 200 games after leaving the Cards. His shining moment was the ’81 postseason: 18 scoreless frames in the first round, and a CG 2-1 victory over Ron Guidry in the pivotal WS Game 5.

— Bibby was given 9 starts, then swapped in ’73 for two players: Mike Nagy wouldn’t last even 9 starts, and John Wockenfuss never got a look before they passed him along, for a guy who never reached the majors. Bibby would go 105-84 with a 104 ERA+ through 1981, and had a 2.08 ERA in 3 starts in Pittsburgh’s postseason run to the ’79 title. Wockenfuss logged 10 useful years as a platoon bat / third catcher / utility man.

— Jose Cruz regressed after a promising rookie year, and was sold to Houston after ’74. He’d be consistently good for the next dozen years, compiling 50 WAR (8th overall for 1975-86).

— After landing Ron Reed for peanuts in mid-’75 (and getting a 3.23 ERA in 24 starts), they turnstiled him into RF Mike Anderson, a former hot prospect with a 91 OPS+ in 1,100 big-league PAs. Anderson never earned a starter’s job, while Reed became a closer for the 1976-78 division-champ Phillies, averaging 2.43 ERA, 15 saves and 120 IP per year. Cards closers wouldn’t do nearly so well in that time.

— Denny alternated good years with bad until they dumped him on the downswing, giving Denny and Mumphrey (both age 27) for the 34-year-old Bobby Bonds, who hit .203 with 5 HRs in 1980 and was released. Denny won the ’83 Cy Young Award and the WS opener.

(After finding these by tracking the ’70s Cardinals, I bumped into this old Hardball Times post covering the same ground — and reasonably projecting four or five division crowns, if they’d only stood pat.)

That decade of bad beats at the swap meet did have an upside, ushering in Whitey Herzog as GM and skipper. Whitey promptly dealt off Simmons, the last of the “5×50” guys — and, in the same deal, two future Cy Young winners, all without much return — but he delivered the ’82 title, three pennants, and MLB’s best record from 1981-89.

CARDINALS SIDEBAR

Who ran this club, Trader Lane? Not every deal cratered, but there’s a fevered quality to all the action, no sense of a long-term plan. Ken Reitz won the Gold Glove in his third year, then was dealt for Pete Falcone, clearing third base for hot prospect Hector Cruz. The next year, after Cruz flopped at third, they sent Lynn McGlothen to get Reitz back. Falcone had two bad years after a good one, so they shuttled him off at 25 for two guys who’d last a total of 35 games, while Falcone logged six more decent years. Those guys weren’t stars, so none of it matters much; but what was the strategy?

From 1970-79, twenty-two different pitchers made at least 15 starts in a year for St. Louis, more than all NL clubs save the ’69 newbies. Nineteen of them were 26 or younger in the first of those years — and 13 of those were traded before age 28:

Years with 15 GS for the ’70s Cards & Traded before Age 28

| Name | Yrs ▾ | From | To | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Denny | 5 | 1975 | 1979 | 22-26 | Ind. Seasons |

| Reggie Cleveland | 3 | 1971 | 1973 | 23-25 | Ind. Seasons |

| Lynn McGlothen | 3 | 1974 | 1976 | 24-26 | Ind. Seasons |

| Pete Vuckovich | 3 | 1978 | 1980 | 25-27 | Ind. Seasons |

| Jerry Reuss | 2 | 1970 | 1971 | 21-22 | Ind. Seasons |

| Pete Falcone | 2 | 1976 | 1977 | 22-23 | Ind. Seasons |

| Eric Rasmussen | 2 | 1976 | 1977 | 24-25 | Ind. Seasons |

| Steve Carlton | 2 | 1970 | 1971 | 25-26 | Ind. Seasons |

| Alan Foster | 2 | 1973 | 1974 | 26-27 | Ind. Seasons |

| Rick Wise | 2 | 1972 | 1973 | 26-27 | Ind. Seasons |

| Tom Underwood | 1 | 1977 | 1977 | 23-23 | Ind. Seasons |

| Mike Torrez | 1 | 1970 | 1970 | 23-23 | Ind. Seasons |

| Nelson Briles | 1 | 1970 | 1970 | 26-26 | Ind. Seasons |

Eight of those 13 started a World Series game after leaving St. Louis: Carlton, Reuss, Torrez, Denny, Briles, Wise, Cleveland and Vuckovich. Underwood pitched in the playoffs for two teams afterward. Even with a pass for Carlton — ownership forced the trade, and it looks worse in hindsight than it did at the time — the balance on these deals still is a pool of red ink. Most were dealt after a bad year, minimizing the return — a common habit of common GMs.

But the man behind most of those trades was the accomplished Bing Devine, who built the title Cards in his first tour (1957-64), then helped mold the Miracle Mets, but didn’t get to enjoy either payoff. Devine returned to the Cards after ’67, but his second stint resembled the work of the man he’d originally replaced in St. Louis — none other than “Frantic” Frank Lane.

__________

In the late ’60s, the Card’ home/road results made a U-turn. From 1960-63, winning years all, their home advantage trailed only the Yankees: .620 at home (3rd in MLB), .465 away. That home edge dwindled in the next few years. And then for five straight seasons, 1967-71, the Cards played at least as well on the road as at home. Their overall record ranked 3rd in this span, but their home/away split was .537-.558. They were the only team in that span that played better out of town. In the ’67-68 World Series, they went 3-4 at home, 4-3 on the road.

It might be just coincidence, but those were also the first five full years in the new Busch Stadium. (Any theories?) Their worst home mark came in 1970, the first with artificial turf; they went 34-47 at home, 42-39 away. That split got more normal in succeeding years, but for their whole turf period (1970-95), the Cards’ home-field advantage was below the MLB average. In their most successful period — three pennants from 1982-87 — it was often said that the speedy Cards were a good turf team. Yet in that span, St. Louis ranked 21st of 26 teams in home-field advantage, and worst of the eight most successful teams. For the pennant years specifically, their combined home edge ranked 22nd — while their record on grass was 80-46, tops on that surface for those years.

____________________

3) Next come the 1991 Astros, finishing last at 65-97 with:

- Curt Schilling, 81 career WAR, age 24 in 1991 (his 4th season)

- Jeff Bagwell, 80 WAR, age 23 (Rookie of the Year)

- Kenny Lofton, 68 WAR, age 24 (debut cameo)

- Craig Biggio, 65 WAR, age 25 (4th year)

- Luis Gonzalez, 52 WAR, age 23 (2nd year)

5-man Totals: 345 career WAR … 13 WAR in 1991

All five were together just that one year.

Three were together for 6 years, 1991-95 and ’97 (Bagwell, Biggio and Gonzalez).

It took six years from this point for Bags and Bidge even to reach October, seven years after that to win a playoff series, and one more year for their only WS appearance … whereupon they were swept. The others listed here were dealt away before the first dance (Gonzalez came back for the breakthrough year), as were ’91 teammates Steve Finley (44 WAR, age 26, 3rd) and Ken Caminiti (33 WAR, age 28, 5th year). (Finley makes the ’91 Astros one of 23 teams with six players age 30 or under who would tally 40+ career WAR, joined by the ’96 Braves — but we’ll save that for another time.)

First out was Lofton, a minor-league star dispatched after a brief trial. Houston had decided to move Biggio from behind the plate, and thought that Ed Taubensee was their catcher of the future. He lasted two years there — and as so often happens, the team that lost the first trade lost the follow-up, too: Taubensee never became a star, but had a decent career with Cincy, while the guys they got back did nothing. Lofton was a smash from day one in Cleveland — ROY runner-up, first-8-years average of .311 BA, 105 runs, 54 SB and 5.9 WAR, with 6 All-Star nods and 4 Gold Gloves. Like Bagwell and Biggio, he never won a championship; but he played in two Series, and reached the playoffs with the Braves, Giants, Cubs, Yankees, Dodgers, and Cleveland (all three tours).

Schilling was next to go: Houston had got him with Finley and Pete Harnisch for Glenn Davis the year before — a huge win on future value, as Davis faded away with back trouble. But Schilling still hadn’t made his bones, and after a 3.81 ERA in 76 relief innings, they passed him to Philly for Jason Grimsley, who had walked 103 and fanned 90 in his first 137 IP. After opening ’92 well in long relief, Schill joined Philly’s rotation on May 19. He had just five starts in his first four years, but rang up a 2.27 ERA in 26 starts, with 10 CG and 4 shutouts, leading MLB in WHIP. Grimsley spent ’92 back in the minors, with a 5.05 ERA, then was non-tendered. A year later, Schilling was NLCS MVP and hurled a World Series shutout.

Finley and Caminiti went together after ’94, in a big Padres swap that brought in Derek Bell, slugger Phil Plantier and some other bodies. Caminiti’s power surged in two steps from a career high of 18 HRs, up to 26 (with a .302 BA) and then 40-.326 and the MVP Award. Of course, we all learned the hard way that he was juicing. Finley also jumped from a high of 11 up to 30 HRs in ’96, averaging 26 HRs from ’96 through ’04.

Gonzalez lasted to mid-’95 in Houston. Like Caminiti and Finley, he had some solid years there, but as yet lacked the power expected from left field. He was dealt to Chicago for catcher Rick Wilkins, who had slumped since his .303/30-HR fluke in ’93, and never broke out of it. Gonzalez went on as before for a few years; then he, too, found power suddenly at age 30, swatting 23+ six years in a row, with a freaky high of 57.

In 1999, Finley and Gonzalez were reunited on Arizona, joining Randy Johnson, who had sealed Houston’s ’98 division crown as a deadline rental. They were the top three in WAR as the second-year D-backs won 100 games and the NL West. Schilling came over in 2000; and with monster years by him, Big Unit and Gonzo in 2001, Arizona won it all.

Houston’s path after assembling these “5×50” talents is no paean to management, but it’s a far cry from the ’70s Cardinals. Their total record from 1991-2005 was 5th in MLB, and they made the playoffs six times in those last nine years (knocked out by the Braves in ’97, ’99 and ’01). Lofton was unproven when dealt, and many top prospects fall short of stardom. Schilling and Gonzalez both had been up for a few years without dazzling anyone. Of the 67 pitchers with 50+ WAR in the live-ball era, none had pitched as much through age 24 and done as little as Schilling (145 IP, 0.2 WAR, 88 ERA+).

ASTROS SIDEBAR

Luis Gonzalez from age 31-35 had a 140 OPS+, 60th on the modern list for that age range (2,000+ PAs). Through age 30, his OPS+ was 109, with more than 4,000 PAs.

There are 200 players whose age 31-35 OPS+ was 120 or better, with 2,000 PAs. Fourteen raised their OPS+ by 30 points or more from what they’d done through age 30 (excluding those with less than 2,000 PAs through age 30). Caminiti is 1st in points gained (+49), Mark McGwire 2nd (+48), Sammy Sosa 5th (+37), Bret Boone 8th (+32), Gonzalez 12th and Jim Edmonds 13th. But there are others who did this before and after the steroids era:

- Roberto Clemente, +43 — 116 OPS+ through age 30, 159 OPS+ for 31-35.

- Augie Galan, +38 — from 107 to 145 OPS+.

- Willie Stargell, +35 — from 136 to 171 OPS+ (7th-best ever for 31-35).

- Adrian Beltre, +34 — from 105 to 139.

- Cy Seymour, +31 — from 104 to 135.

- Jim Hickman, +31 — from 94 to 125.

- Frank Howard, +30 — from 131 to 161.

- Hal Chase, +30 — from 102 to 132. (Oh, what the hell … let’s say he used sheep testes.)

Next down that list are Honus Wagner, +28 (155 to 183, 3rd all-time), and Dixie Walker, +28 (110 to 138).

Some people assume that Gonzalez and Finley used steroids, just because of their 30s power surge. Neither was ever suspended for PED use, nor named in the Mitchell Report. I have no other information on this score; does anyone?

But here’s the point: What’s odd about that line of thinking is that, although Bagwell and Biggio both had mid-career power surges, only one has been broadly tarred with steroids innuendo:

- Craig Biggio averaged 7 HRs in his first 4 full years, age 23-26. He leaped to 21 HRs at 27, and remained a steady 20-HR man through age 40, averaging 18 HRs in that span, and 24 HRs from age 38-40.

- Jeff Bagwell averaged 18 HRs in his first 3 years, age 23-25. He leaped to 39 HRs at 26, and averaged 36 HRs from age 26-36.

Whatever the logic of suspicion based on a power spike, it applies equally to Bidge and Bags. So does guilt-by-association: Both played with Caminiti, and were ’93 spring training teammates of Jason Grimsley, a central figure in the Mitchell Report. Both also played with admitted HGH user Andy Pettitte and accused doper Roger Clemens, although that came near the end of Bagwell’s career.

Advanced stats and at-the-time accolades favor Bagwell as the better player: He won an MVP Award, and got MVP votes in 10 seasons, while Biggio peaked at 4th place and got votes in 5 years. Bagwell earned half again more money than Biggio, despite a shorter career. But Biggio fared better in HOF voting right from the start, with 68% in his first vote and induction in his third, while Bagwell hasn’t reached 60% in five tries. In three shared ballots, Biggio outpolled Bagwell by an average of 75%-57%. I don’t get it.

____________________

4) Lastly, the 1996 Braves: 96-66, but just short of a second straight championship, with:

- Greg Maddux, 107 career WAR, age 30 in 1996 (his 11th year)

- Chipper Jones, 85 WAR, age 24 (3rd year)

- Tom Glavine, 81 WAR, age 30 (10th year)

- John Smoltz, 70 WAR, age 29 (9th year)

- Andruw Jones, 63 WAR, age 19 (debut cameo)

5-man Totals: 406 career WAR … 26 WAR in 1996

All five were together for a 7-year span, 1996-2002 (though Smoltz missed 2000).

All three pitchers were together for a 10-year span, 1993-2002.

The lone rival to the Grove/Foxx Athletics in this little study, in terms of both talent and tenure together. The A’s group lasted one year longer, but each group had 5 years when all were regulars. None of these Braves played for all 14 division winners from 1991-2005, but each man won at least 10 (Smoltz 13, Glavine and Chipper 11), and the whole group shared six crowns.

Other ’96 notables: Fred McGriff, 52 career WAR (age 32); David Justice, 41 WAR (age 30); Javy Lopez, 30 WAR (age 25); Marquis Grissom, 29 WAR (age 29); Terry Pendleton, 28 WAR (age 35); Ryan Klesko, 27 WAR (age 25); Jason Schmidt, 32 WAR (age 23).

The ’95 Braves had a payoff moment like that of the ’20s Athletics: After losing two World Series and an NLCS from ’91-93, losing ’94 ROY favorite Chipper to a late-spring torn ACL, and seeing that postseason scotched by the strike, Atlanta finally took the title. Every soul in baseball foresaw more to come.

The next summer, Smoltz made it six straight Cy Young Awards for the Big Three, and Chipper made his first dent in the MVP vote. Andruw came up that August, blasting through three minor-league stops at 19, homering in the NLCS clincher and twice in the WS opener — the youngest ever with Series yard work, plating 5 runs in his first two times up in Yankee Stadium. When Maddux stoned the Yanks in Game 2, the monkey seemed off their back for good, and the Bronx air smelled of dynasty.

A crystal ball at that moment would have shown this in the next six years:

- Maddux, 108-48, 2.77 ERA, 157 ERA+, 5th in pitcher WAR.

- Glavine, 103-51, 3.25 ERA, 134 ERA+, 9th in WAR, and another Cy Young Award.

- Smoltz, 43-23, 3.04 in three years before injury struck, then an NL-record 55 saves in his first full turn at closing.

- Chipper 7th in total WAR, averaging .316-33-107 and 6 WAR, with the ’99 MVP.

- Andruw (3rd in WAR) becoming the greatest defensive outfielder since(?) Willie Mays, with more homers by age 25 than Hank Aaron.

Improbably, this also was written in the stars:

- No World Series games won since that Maddux whitewash in ’96 Game 2.

After dropping the last four games in ’96, Atlanta won its division for nine more years, right on through Smoltz’s surgery and the free-agent departures of Glavine (after 2002) and Maddux (’03). But they lost the ’97-98 NLCS by 4-2 each; got swept in the ’99 WS and the 2000 first round; were crunched 4-1 in the ’01 LCS; and lost the LDS from 2002-05.

Their .604 winning percentage from 1996-2005 is the second-best 10-year span with no championships, trailing only the Dodgers of 1945-54 (.607). Brooklyn broke through at the end of that stretch, whereas the Braves tumbled under .500. But that was no fault of Smoltz (16-9, 211 Ks, 5.9 WAR at 39), or Chipper (.324 BA/1.005 OPS in 110 games at 34), or Andruw (41 HRs, 5.6 WAR) — and in spite of recent system products Brian McCann (.333/.961 in his first full year) and Adam LaRoche (.285 and 32 HRs). Rather, it was the rest of the pitching staff: Non-Smoltz starters let in 5.58 runs per 9 innings, and the closing committee blew 28 of 48 save tries before Bob Wickman was brought in at the deadline. For the first time since 1990’s last-place finish, Braves pitching was worse than average.

Many other fine players came and went in the long run of excellence, especially outfielders: Ron Gant (34 career WAR), David Justice (40 WAR), Ryan Klesko (27), Marquis Grissom (29), Brian Jordan (33), B.J. Surhoff (34), Reggie Sanders (40), Gary Sheffield (60), J.D. Drew (45). Some were let go as free agents and had good years afterwards, but it’s hard to fault the overall strategy. After all, you can’t finish higher than first place. Atlanta’s payroll was #1 just once from 1991-2005, never above #3 in the last 10 years.

Some blame the offense for the fall disappointments — or, putting that another way, some think too much team strength was packed into the rotation. A quick check suggests otherwise. For 1996-2005 postseason games:

- Atlanta went 37-41, scoring 4.2 runs per game and yielding 3.9.

- All other NL teams went 116-130 — virtually the same W% as Atlanta — scoring 4.1 runs and allowing 4.3.

- The Yankees went 74-41 (4 titles, 6 pennants), scoring 4.4 and allowing 3.8 — with a DH in most of those games.

The Braves’ postseason punch rivaled the Yankee dynasty, once you adjust for the DH. They scored more and yielded less than other NL teams, but fared no better.

Meanwhile, the Big Three’s combined postseason performance was such that, if the Braves had won more titles, the aces would have been hailed as a big reason why. There’s a better case that they didn’t get enough from their 4th starters, than there is that the team was rotation-heavy. Comparing 1996-2005 postseason starts by Maddux, Glavine and Smoltz to those of other Braves:

- Big Three: 2.92 ERA, 3.62 RA/9, 6.6 IP/G (53 starts, 22-23 individual W-L)

- All others: 4.61 ERA, 4.87 RA/9, 5.5 IP/G (25 starts, 6-10 individual W-L)

And for the whole 1991-2005 playoff run:

- Big Three: 2.95 ERA, 3.55 RA/9, 6.6 IP/G (86 starts, 36-32 individual W-L, team 46-40)

- All others: 4.01 ERA, 4.29 RA/9, 5.7 IP/G (39 starts, 11-13 individual W-L, team 17-22)

Others point to Bobby Cox’s disdain of marquee closers. But besides Mo Rivera, non-Braves WS-winning closers from 1991-2005 converted 81% of postseason save tries (47 of 58), with a 2.66 ERA. Atlanta’s closers converted 21 of 28, 75%, with a 2.57 ERA. The difference between 75% and 81% is less than two games. Even the difference between 75% and Mariano’s career 89% is just four games. Atlanta went 3-4 when their closer blew the save, and one of the losses came in the ’95 championship. Smoltz was an elite closer from 2002-04, but they lost each first round anyway. Were Atlanta’s closers really a main difference between dynasty and disappointment?

Those who seek “character” in close games and title tilts may groan at this suggestion, but the whole bridesmaid syndrome could be laid on unlucky run distribution. Atlanta outscored the ’91 Twins, ’92 Blue Jays and ’96 Yanks in those WS losses (75-59 combined). They topped the ’93 Phils in the NLCS by nearly 2 runs per game (+16 in two wins, -6 in four losses). They nosed the ’97 Marlins by one run in the NLCS, and the ’02 Giants by two in the NLDS.

“Just a bunch of stuff that happened” is a punchline in place of a moral, not a satisfying summation of 13 October ousters. But if there’s a better explanation, I’ve yet to find it. The Boys of Summer dropped five of six World Series, but four of them made the Hall anyway. Bobby’s Braves will fare at least that well in Cooperstown — Chipper in 2018 should be their 4th first-ballot selection, and Andruw looks good by the HOF Monitor, JAWS and Hall of Stats. No one should doubt their greatness, even with just one ring.

BRAVES SIDEBAR

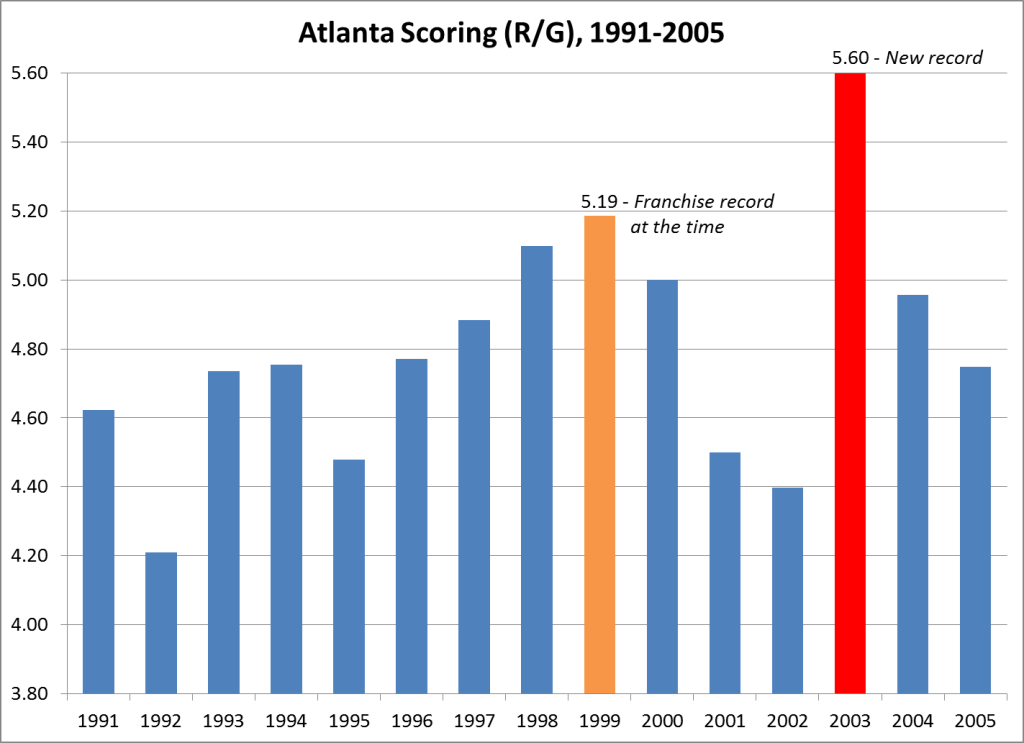

Atlanta won 101 games in 2002 and ’03, despite an amazing reversal of team strength:

- 2002: 1st in run prevention (3.51 R/G), 9th in scoring (4.40)

- 2003: 9th in run prevention (4.57 R/G), 1st in scoring (5.60)

I haven’t studied such things, but I doubt there’s been another switcheroo like this, without a change in home parks. In a single year, scoring in Braves games increased by 1.26 runs, or 29% — even though their one-year home park factor went down sharply (106 to 96). Scoring in their road games jumped by 33%.

Chipper and Andruw had worse years in ’03 than ’02, but Javy Lopez went nuts, Sheffield had his last great season, the keystone tandem of Marcus Giles and Rafael Furcal had career years, and there wasn’t a weak spot in the lineup. On the pitching side, Glavine had left, Maddux stepped down to merely good, and the bullpen beyond the sublime Smoltz was a smoking ruin (nearly 5 runs per 9 IP).

Their 5.60 scoring average was a franchise record since 1901, by a margin of 0.41 over their next-highest year (1999) — and more than every AL team but one that year:

It’s the only time since 1983 that Atlanta led the NL in scoring. The increase of 1.20 R/G over the year before was the club’s biggest since 1925, which had followed the lowest-scoring year by any team in that whole decade.

But all the firepower went for naught: They hit .215 with 3 runs per game in the LDS, totaling 4 runs in three losses to Kerry Wood and Mark Prior.

____________________

So, how would you rank these four collections? It’s a two-way battle for the top spot, and a doozie. The Braves’ case:

- Most career WAR (407-377).

- Best WAR and only pennant of these “30-and-under” years.

- Five great players versus four.

And for the A’s:

- Best pitcher and best position player in this fight.

- Both quintets averaged 24.9 WAR in their years together, but the A’s did it one year longer.

- Their 8-year record was better than Atlanta’s 7-year mark (.629-.610).

- Two championships versus none.

- In the discussion for greatest team ever.

It’s close, but I’ll take the A’s. Not just for the titles; those have a random element, especially in the Braves’ era of three rounds. Five players can’t make a champion, and besides, Atlanta won just before Andruw arrived, while Rommel wasn’t a huge force in Philly’s crowns. Still, titles have to count for something in this matchup, and the Braves didn’t really come close to one with this quintet. None of their five lost WS and LCS went the distance; their record in those tilts was 7-20, 2-8 in the Series. The A’s won two World Series handily against the two best NL teams of that era, the Cubs and Cards. It’s a toss-up on talent, but the trophies break the tie.

- 1925-28 A’s: 377 career WAR … 24 WAR in ’28 … 3 pennants, 2 championships

- 1996 Braves: 406 career WAR … 26 WAR in 1996 … 2 pennants … 7-6 in playoff series with all 5 players

- 1991 Astros: 345 career WAR … 13 WAR in 1991

- 1970 Cards: 311 career WAR … 13 WAR in 1970

The 20 players ranked by WAR:

- (PHA) Lefty Grove, 110 WAR

- (ATL) Greg Maddux, 107 WAR

- (PHA) Jimmie Foxx, 96 WAR

- (STL) Steve Carlton, 90 WAR

- (ATL) Chipper Jones, 85 WAR

- (ATL) Tom Glavine, 81 WAR

- (HOU) Curt Schilling, 81 WAR

- (HOU) Jeff Bagwell, 80 WAR

- (ATL) John Smoltz, 70 WAR

- (PHA) Al Simmons, 69 WAR

- (HOU) Kenny Lofton, 68 WAR

- (HOU) Craig Biggio, 65 WAR

- (ATL) Andruw Jones, 63 WAR

- (STL) Dick Allen, 59 WAR

- (STL) Joe Torre, 58 WAR

- (STL) Jose Cruz, 54 WAR

- (PHA) Mickey Cochrane, 52 WAR

- (HOU) Luis Gonzalez, 52 WAR

- (PHA) Eddie Rommel, 50 WAR

- (STL) Ted Simmons, 50 WAR

| PHA | ATL | HOU | STL | |

| Lefty Grove | 110 | |||

| Greg Maddux | 107 | |||

| Jimmie Foxx | 96 | |||

| Steve Carlton | 90 | |||

| Chipper Jones | 85 | |||

| Tom Glavine | 82 | |||

| Curt Schilling | 81 | |||

| Jeff Bagwell | 80 | |||

| John Smoltz | 70 | |||

| Al Simmons | 69 | |||

| Kenny Lofton | 68 | |||

| Craig Biggio | 65 | |||

| Andruw Jones | 63 | |||

| Dick Allen | 59 | |||

| Joe Torre | 58 | |||

| Jose Cruz | 54 | |||

| Mickey Cochrane | 52 | |||

| Luis Gonzalez | 52 | |||

| Eddie Rommel | 50 | |||

| Ted Simmons | 50 | |||

| Team Total | 377 | 407 | 346 | 311 |

____________________

Notes

* Players appearing for more than one team in a season were ignored in these counts, due to how the data was gathered: A general search with the Baseball-Reference Play Index gives transferred players no team identity, and to track them all down is a lot of work for a little info. It’s possible that some teams missed the study due to an ignored transfer year; two of the four teams above had all five players together for only one season.

Also, I rounded WAR to the nearest whole number (so 49.6 = 50), and for pitchers I used what I call “best WAR” — the higher of pitching WAR alone, or the sum of pitching and hitting WAR. This credits good-hitting pitchers for that value, without punishing bad-hitting pitchers. Ten out of 103 studied pitchers with 50+ “best WAR” needed WAR/pos to clear the threshold, most notably Wes Ferrell and George Uhle; but none of those ten turned up on the “5×50” teams.

Was surprised that none of the 90s Cleveland teams made it. Actually the ’96 team did have 5 of 50+ under 30 (Kent, Giles, Lofton, Thome and Ramirez) but fell through the cracks because Kent only played part of the year with Cleveland (per John’s note).

Dropping the criteria to 40+ adds in Belle and Vizquel. And dropping it to 20+ adds in Nagy, McDowell and (kind of) Burnitz (19.7 WAR) and Baerga (19.5).

David P — I’m working up a list of 40+ WAR, 30 or younger, and at least 1 WAR in the season. Cleveland ’96 is one of a dozen or so with 6 such players. (This list will have the same partial-year exclusion, alas, but Kent didn’t reach 1 WAR with CLE that year.)

Thanks John! I doubt many Cleveland fans even remember Kent’s tenure with the team, given how brief it was.

David P, any Cleveland fans that recall Kent’s brief stay can at least take heart in parlaying him into a few good years from Matt Williams & Travis Fryman.

Mets fans, on the other hand … We dealt David Cone to get Kent, then swapped him for Carlos Baerga right when he nosedived at age 27. Both Cone and Kent averaged 5+ WAR in their next 7 years after leaving the Mets. Either one of them might have put the late-’90s Mets over the hump.

P.S. Odd fact about Kent and SS Jose Vizcaino — They were traded together twice within 4 months, landing in the postseason both times (’96 CLE, ’97 SFG). Split up after ’97, they reteamed with Houston in ’03, and made the playoffs in ’04, after which Kent moved on again. So, in 3-1/3 years together after leaving the Mets, Kent and Vizcaino had postseason berths with 3 different teams.

Just a phenomenal analysis, John, on a topic none of us knew we were dying to learn about. Having read my thoughts on the game’s evolution, you won’t be surprised to hear that I’d take the Braves. Grove and Foxx dominated very different competition, exceeding a very different replacement level by moderate amounts. I’ll grant you that those depression-era A’s teams, when the stars matured, were incredible.

I wonder how many World Series the Braves would have won if not for the Wild Card.

John, this was just epic. Now I’ve got to go read the non-Braves part!

John,

Great analysis of an interesting topic. Those Braves teams were certainly the best the NL had to offer from about 1991 – 2002 (?). I was OK with two-division baseball and a mere LCS to decide a pennant. Things have gotten quite convoluted. I don’t think it’s a matter of “clutch”, either. If you invited a sub-.500 team as the 2nd Wild Card they might even upset some apple carts on the way. It would have been interesting to see how 1994 would have played out with all that Montreal talent. I’m still taking the Philadelphia A’s and wondering how things would have turned out for them if Mack didn’t have his fire sale.

I recall the Astros giving up Rusty Staub and Joe Morgan. They would have made a nice tandem with Jim Wynn, Bob Watson, Cesar Cedeno, Cliff Johnson, and Doug Rader. The only thing the Astros didn’t have was a SS who could hit. Oh wait, they traded Dennis Menke as well as Mike Cuellar….Once again, baseball imitates life as impatient management makes mistakes at the top and continues to disappoint “shareholders”.

The Hardball Times website did a series of “what if” articles recently based on GM moves that impacted various pennant races and league standings in the ’60’s and ’70’s. Fascinating stuff…

John,

Perhaps even more ‘pointedly’ in regard to the steroids discussion, Gonzo and Caminiti are 8th, all-time, for OPS+ at age 33 in a qualified season at 174. Going into those seasons, Gonzo was up to 115 OPS+ and Caminiti only 103. Caminiti won the second half of the season Triple Crown and an MVP award. Gonzo slugged 57 homers and at one point fairly late in the season was on pace to break the all-time total bases record. The bums ahead of them on the list:

1 Babe Ruth 206 1928

2 Lou Gehrig 190 1936

3 Honus Wagner 187 1907

4 Willie Stargell 186 1973

5 Barry Bonds 178 1998

6 Rogers Hornsby 178 1929

7 H Killebrew 177 1969

8 Luis Gonzalez 174 2001

9 Ken Caminiti 174 1996

10 Ed Delahanty 174 1901

Except for the time when Don Coryell was in St. Louis, the decade of the 1970s was a tough time to be a Cardinal fan. Easy to get box seats, though.

Fascinating post, JA. I’ve been a Mets fan for 50 years, and it can be a tough row to hoe sometimes, but I really feel sorry for those Astros fans. Longest stretch of regular season game wins between World Series game wins:

Cubs (1946-current) 5,095

Phillies (1916-1980) 4,440

Astros (start to current) 4,120

Senators/Rangers (start-2010) 3,747

White Sox (1960-2005) 3,705

Indians (1949-1995) 3,675

Expos/Nats (start to current) 3,527

Rumored that Andruw Jones will be back in North American baseball soon.

Despite all of those homers, Jones wasn’t valued by WAR very much on offense.

Here’s the players with 60+ WAR and Rbat under 125:

60.5 / 43.8 … Willie Davis

62.8 / 119.3 .. Andruw Jones

65.5 / 120.2 .. Willie Randolph

66.1 / 110.0 .. Buddy Bell

66.3 / 31.3 … Pee Wee Reese

68.0 / 102.2 .. Graig Nettles

68.4 / 73.7 … Ivan Rodriguez

76.5 / -116.8 . Ozzie Smith

78.3 / 42.7 … Brooks Robinson

Voomo, do you see ‘Druw getting elected by the BBWAA? I don’t, unless the writers see him as an Ozzie/Brooks Robinson type and give him a “best ever” tag for his defense in center. Problem, though: Ozzie and Brooks were still bringing all-world defense well into their late 30s, while Jonesie flamed out much earlier.

Then add in the fact that writers may not give Andruw full credit for his 400+ homers because of the era he played in. And I can say this, since I’m a Braves fan: there is little doubt that he was on ‘roids near the end of his prime, though he never was caught. Before the 50-HR season came a much bigger-looking Andruw whose head size had swelled overnight. No, I’m not the steroid police disavowing Jones’ career from some moral/ethical slant, but there are several badge-carrying members of the BBWAA who think they are and will ding Andruw for that.

So I don’t see it for Jones as far as the writers are concerned. He will have to get in via a VC vote later on down the line. I would vote for him because maybe the best numbers-based fielding prime that the game has ever seen, but I’m a biggish Hall kind of guy. I won’t shed any tears if he doesn’t make it.

bstar, I won’t dispute those points on Andruw’s HOF chances. But I’ll note that his 10 straight Gold Gloves are a powerful marker.

All 11 eligible players with at least 9 Gold Gloves at C, 2B, SS, 3B or OF have been elected by the writers: Bench, Alomar, Sandberg, Ozzie, Aparicio, Brooksie, Schmidt, Mays, Clemente, Griffey and Kaline.

Only Mays and Clemente had more as outfielders, and only Mays had more as a CF. (Three other OFs tied Andruw with 10 Gold Gloves: Griffey all in CF, Ichiro all in RF, and Kaline 8 in RF and 2 in CF.)

It’s hard to predict what folks will remember in 2018, when Andruw hits the ballot. But it seemed to me he was widely viewed as an historic defender in his prime. Come 2018, both the stats and the hardware will still be there to remind the voters.

I have to agree with Bstar re: Andruw Jones and his HOF chances. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if he was one and done.

Other points against him include:

1) A .254 BA in an offensive era. Heck, even Ozzie hit .262.

2) He’ll be viewed as the 5th best member of a team that only won one World Series.

3) Basically did nothing in his 30s. A grand total of 4.9 WAR. I’d be shocked if the BBWAA has ever elected a position player who did so little in his 30s.

4) The ballot will still be extremely crowded.

Of the people currently on the ballot, I expect that Piazza will have been elected. And possibly Bagwell though I have no certainty on that. But I expect all of the following to still be on the ballot: Schilling, Clemens, Bonds, Edgar, Mussina, Kent, McGriff, Walker and Sheffield. Possibly Sosa. Possibly Garciaparra.

And lots more will be added to the holdover list. I expect Trevor Hoffman to be there. Possibly Edmonds and Billy Wagner. I doubt Vladimir or Pudge get elected their first year so they’ll be there. No idea if Manny will get 5%+ but it’s certainly possible.

Joining Andruw his first year on the ballot are Chipper and Thome. Plus Rolen. And Vizquel will likely draw some votes.

5) As for John’s point about the Gold Glove and the Hall, I don’t find it particularly compelling. Eight of the 11 players on his list were clearly better than Jones. Two others – Alomar and Sandberg – were arguably his equal. But they were second basemen who could also hit which gives them a big advantage. That leaves Aparicio, a mediocre selection from 30 years ago on a fairly empty ballot.

David: regarding your point 3).

BBWAAA-elected Hall of Fame position players, less than 10 WAR in their 30s:

Ralph Kiner (5.8)

George Sisler (6.6)

Joe Medwick (8.5)

Kiner and Medwick were both elected 20 years after they retired. Sisler’s first half of his career (as discussed on a recent CoG thread) was great enough to get him in on his fourth ballot appearance.

David — Fair point about that GG list. But I’ll counter yours re: “did so little in his 30s”:

First, you’re right that no BBWAA position player had as little WAR in his 30s as Andruw’s 4.9 WAR. But the bottom three are close enough to make the distinction meaningless: Kiner 5.8, Sisler 6.6, Medwick 8.5.

More importantly, to anyone hung up on Andruw’s WAR in his 30s, I would say this:

— Andruw *before* age 30 did FAR MORE than most BBWAA position players. The median there is about 44 WAR; Andruw had about 58 WAR.

— Bottom line, Andruw’s 62.8 career WAR is better than 21 of the 74 BBWAA position players. His rate of WAR per game is above 30 of those 74. And he beats 15 of them on both counts.

So, what rationale exists for dinging him for low value in his 30s, that isn’t more than offset by his huge value in his 20s?

I know we’re just trying to anticipate what the writers might think. But honestly, if any of them is thick enough to get hung up on the age-30 division, there’s no hope of predicting what else he might think.

One thing that Jones has working against him- that relates to his turning 30- was the contract he signed with the Dodgers and how awful he was that season. With the single exception of ARod’s renegotiating his contract with the Yankees it was by far the most publicized and talked about free agent signing of that offseason (only Torii Hunter’s moving from the Twins to the Angels and Mariano Rivera’s re-upping with the Yankess came anywhere close).

And while he did rebound from that epically bad year, he did so while only playing part time and hitting below .230 in 3 of the next 4 years so at least superficially his numbers don’t look all that impressive.

I don’t know that the age-30 cutoff point will necessarily be a big factor but I can sure see a lot of writers thinking of him as turning into a bad to mediocre player at a fairly young age.

And fair or not, I can also see that reflecting on how they think of him when he was in his prime as well.

Frankly, I’ll be amazed if he ever reaches the Don Mattingly or even Dale Murphy level of support among HOF voters.

Thanks John. And now for my counter. 🙂

1) If you have to go back 30+ years, you’ve pretty much proved my point. And there’s not a single BBWAA voter who cares about what was done way back then. They care about their own personal standards for the HOF.

2) While it’s interesting that Jones has more WAR than 21 of 74 BBWAA elected position players (does that include catchers???), no one has ever been elected because of their WAR. Most of those players were elected long before WAR was even invented. And those that have been elected since…it’s never been the primary consideration for the electorate as a whole.

Beyond that too much of Jones WAR is tied up in defensive value. To the extent that voters value WAR, many are still going to take a dim view of the defensive portion.

3) Do you remember that there was another CFer on the ballot a few years ago? This one had even more WAR than Jones (68.2 to be exact). He got a whopping 3.2% of the vote and fell off the ballot his first year. That would be Kenny Lofton of course.

I predict a very similar fate for Jones. He has 0% chance of being elected by the BBWAA and about a 10-25% chance of lasting for more than one ballot. Whether or not he deserves election is another question entirely.

David — Aren’t you having it both ways regarding WAR? You cited Andruw’s low WAR in his 30s, then you say no one gets elected for his WAR.

I agree that WAR has but a small effect on the writers’ vote. I merely used it as a convenient tool to counter your “4.9 WAR in his 30s” point. (BTW, yes, catchers were included in stating that Andruw has more WAR than 21 of 74 writers’ selections. Removing catchers, his WAR tops 16 of 66, with 5 more within 2 WAR of Andruw.)

I’ll come back to the “30s” angle at the end of this comment. On your other points:

Lofton’s rejection might predict Andruw’s fate, but it might not. The voters have always undervalued leadoff men. I suspect Lofton went down mainly due to career totals of 130 HRs and 781 RBI.

“If you have to go back 30+ years, you’ve pretty much proved my point. And there’s not a single BBWAA voter who cares about what was done way back then.”

— That clearly oversells the point. Most of the BBWAA voters actually do remember more than 30 years of baseball. I don’t know their average age, but I’d be shocked if it’s under 50. They have to be in the BBWAA 10 years before they even get a HOF ballot.

About the large share of Andruw’s value tied up in defense: There are at least 4 writers’ selections who clearly would not have sniffed the Hall based on their bats: Ozzie, Brooksie, Aparicio and Maranville. Granted, they’re all infielders, and one of them played 70 years ago. But I don’t see why the same voters who went for Ozzie might not go for Andruw.

Now, to put this “30s” angle to rest … Age cutoffs make no sense in comparing players who broke in at different ages. Andruw debuted at 19 and was a 3-WAR regular at 20. If any such division is meaningful at all, it should be at a number of seasons played, not an age.

Andruw’s age 30 was his 12th season. So let’s compare to BBWAA selections from their 12th season onward. (Again, WAR is just shorthand for value that could be expressed in more old-fashioned ways.)

2.4 WAR, Cochrane

3.1 WAR, Puckett

3.8 WAR, Sisler

[4.9 WAR, Andruw]

5.3 WAR, Boudreau

5.9 WAR, Medwick

7.5 WAR, Rice

8.1 WAR, DiMaggio

8.2 WAR, Simmons

8.4 WAR, Brock

8.4 WAR, Snider

That’s 10 BBWAA selections quite similar to Andruw in WAR from 12th year onward. Four more had less than 10 WAR in that span.

Andruw’s length of time as a great player simply is not unusual among writers’ selections.

Other ways to look at it:

— Years with at least 3 WAR: Andruw had 11. 28 of the 74 writers’ selections had fewer.

— Years with at least 4 WAR: Andruw had 8 (all 4.9 or higher). 24 writers’ selections had fewer.

— Years with at least 5 WAR: Andruw had 6 (all 5.6 or higher). 27 writers’ selections had fewer.

— Years with at least 6 WAR: Andruw had 5 (all 6.6 or higher). 38 writers’ selections had fewer.

— Years with at least 7 WAR: Andruw had 3. 35 writers’ selections had fewer (including 11 with none).

Andruw’s number of years as a *good* player is not unusual for BBWAA selections, whether you use 3 or 4 WAR for that threshold.

And his number of *great* years is above the median for that group, whether you use 6 WAR or 7 WAR for that threshold.

People will think what they want, but I don’t see a reasonable case against him based on career length or number of good years.

John – I wasn’t trying to have it both ways re: WAR, though I can see how it looks that way. I was simply using WAR as a shorthand for how little Jones did in his 30s. There were plenty of other measures I could have used as well.

Lofton mainly went down because of the overcrowded ballot. There were lots of voters who wanted to vote for him but didn’t have room on their ballot. As I’ve already demonstrated, the exact same thing will happen with Jones. Which is one of the reasons why looking back 30+ years isn’t helpful…the ballot landscape has changed considerably over that.

And sure, there are voters who remember 30+ years of baseball history. But they’re not interested in or concerned about the ballot intricacies of what happened 30+ years ago. And sure, it may make more sense to look at years in MLB rather than age. But do you really think the voters are going that far into the weeds? I guarantee you we’ve already spent more time discussing and analyzing Andruw Jones than what the majority of voters will do.

BTW, here’s the entire list of HOFer (regardless of election method) with a batting average lower than Andruw Jones.

Ray Schalk

That’s it.

Well, this may be a moot discussion for a bit. Andruw wants to return to MLB after two years in Japan. If he makes it, then his ballot entrance will be delayed.

http://hardballtalk.nbcsports.com/2015/02/01/andruw-jones-aiming-to-return-to-major-league-baseball/

Which means it will be Omar Vizquel to first break the trend of 10 or more Gold Gloves being an auto-ticket to Cooperstown.

Vizquel is basically Luis Aparicio minus all that baserunning value and MVP support.

Or he’s Rabbit Maranville minus the narrative. Rabbit actually was quite famous.

Shunning Vizquel might make it easier for voters to deny an all-time-great fielder like Andruw.

I don’t think Jones has enough left in his bat or glove to change the conversation if he does make an MLB roster this year, but delaying his debut on the ballot by a few years means he will be judged by a slightly less old-school-based body of voters. WAR is his only shot but the odds are long.

If the panel will excuse a brief off-topic interjection, I have one small quibble with what will become the defining narrative of Super Bowl 49.

Everyone is focused on that last play call.

Okay, of course, up the middle with the Beast was the obvious play.

I can’t argue that.

The difference in the game, however, was a play call early in the 2nd half.

I stated this out loud at the time it happened:

(nobody heard me, however, as somehow I ended up at a Super Bowl party with a bunch of 20 somethings, none of whom were exclusively focused upon the game.

In fact, one blond boy in a white sweater was staring at his phone during the Gronk touchdown, and Never Looked Up, while expressing his genuine happy anticipation of getting to see Katy Perry. !

(There was a 10 foot wide HD screen at this party, however, and some excellent guac)).

Anyway, I called it, when the Hawks took the field goal from the 8, on 4th and 1.

I said “Game over. The Pats will win the game by 4 points or less.”

You want to talk about not giving Beast the ball on the goal line?

What about 4th and one? You’re at the 8. You need one yard to continue the drive. You need touchdowns to beat New England. Not field goals.

I know that I’m in the minority here.

Everybody says ‘take the points.’

I don’t see it that way. From my perspective, Seattle conceded 4 points to Boston. Ballgame.

“What about 4th and one? You’re at the 8. You need one yard to continue the drive. You need touchdowns to beat New England. Not field goals.”

Packer fan here… don’t get me started.

But man alive, that was the PERFECT ending to the game. Seattle, you lost in heartbreaking fashion? At the very end? And questionable coaching was partially to blame? BOY THAT MUST FEEL AWFUL.

Nice to see Seattle live up to their classy reputation by immediately starting a fight on the field once it became clear they weren’t going to win.

brp,

If Rodgers is healthy, the Packers go for the TD’s (twice) and probably succeed at least once. I guess McCarthy didn’t have a 4th and 1 for a limping QB? But, if #85 blocks for Nelson on the on-side kick, instead of trying to catch the ball, Jordy catches the ball and Rodgers is on his way to Disney

I don’t know if folks here read Grantland.com at all (although I suspect this would be a crowd that would enjoy the stats-savvy, mainstream-media-sports-coverage-mocking approach they have), but there was an amusing joke theory put forth there that the Detroit Lions’ eternal curse was carried forward, from the reversed call in the Dallas game, to the Dez Bryant catch/no-catch in the Green Bay game, to the heartbreaking/bewildering loss that Green Bay suffered to Seattle… predicting (the article was before the Super Bowl) that Seattle had to lose in heartbreaking fashion.

As a (sadly) lifelong Lions fan, I have to hope that this is somehow true and their curse of ineptitude will be lifted. Or else I’ll have to suffer further ignominy like when the halftime show started with Katy Perry riding out on that 15-foot animatronic lion and my friend saying ‘well, that’s the first time a lion has been in the Super Bowl’.

Teams leading at the end of the third quarter went 6-4 in this year’s NFL playoffs. Detroit lost to Dallas, Dallas lost to the Packers, Green Bay lost to Seattle, and Seattle lost to the Patriots.

Fellow Packer-backer here. I was vindictively smiling at the end of that one, for sure. Don’t get me wrong – I really like Russell Wilson. But I wasn’t sad to watch Seattle lose that game.

Voomo:

Was it any worse than in the Rose Bowl against Vince Young and Texas, Carroll and USC going for “it” on 4th down with LenDale White (and his 4.85 40) while Reggie Bush (4.4 40-the second coming of Gale Sayers)is standing on the sideline? Certainly USC couldn’t stop Texas all day and had to try to get a first down but, for crissake, how about giving the ball to Bush? Same deal with Lynch – most TD’s and yards in the NFL in the last 4 years. Or, how about letting your athletic QB roll out and decide whether to run it in, pass it, or throw it away?

What I hate about all the hullabaloo surrounding the play call is anyone watching witnessed perhaps the single most influential defensive play in the history of the Super Bowl, or perhaps in pro football history.

We saw perhaps pro football history’s best example of snatching victory from the jaws of defeat.

And instead of celebrating that play, we are deriding the play call, even though we know deep down that it’s not the play call in and of itself that decided the game. It was the great job of jumping the route by the defender that decided it.

We always have a choice. We can celebrate the winners or fashion goat horns for the losers. I find it more than a bit nauseating that anymore we constantly choose the latter.

The problem with the play call is that it was a classic example of poor coaching. If the definition of good coaching is putting your players in the best position to succeed, i.e. getting your personnel into situations that enable them to do things they are good at, and getting the opponent to attempt to do things they aren’t as good at, then what the Seahawks coaches did here was anti-coaching. I can’t claim that is why the public is disparaging the play call, but as a former Swiss football coach (which should be an oxymoron, I know) it is why I did.

The idea, especially with the game – the Super Bowl no less – on the line, is to call a play that has a high chance of succeeding while keeping an eye on relative risk. The play Seattle called needed, for a high chance to succeed, to have Seattle WR Kearse make a play across from Patriot DB Browner that, on the one-yard line, he cannot physically execute in anything like a consistent manner. It plays 100% to Browner’s strengths, not Kearse’s. Once Browner jams Kearse (and it wouldn’t surprise me if former Seahawk Browner jammed Kearse consistently on similar plays in Seattle’s practices last season), the basis of the play design is destroyed: Patriot DB Butler (the hero of the game indeed) can’t effectively be rubbed. He has the space, the lane he needs, to drive on the ball. So you are left with a highly inexperienced receiver, Lockette (a speed guy, a converted track star with 18 catches) trying to overcome a defender (also inexperienced, admittedly) who hasn’t been rubbed and can therefore jump the route as QB Wilson throws a pass not ideally suited to his otherwise considerable talents. (If it were Brady or Rodgers or, hell, Jay Cutler throwing this pass, that would be another matter. Russell, not so surprisingly, executed it very poorly.)

There are all kinds of equivalents in baseball. Maybe Game 6, bottom of the 11th of the 1991 World Series. Kirby Puckett of the Twins leading off in the Metrodome, and Bobby Cox going with Charlie Liebrandt. I don’t know Puckett’s stats against LH junk ballers off the top of my head, but if I remember correctly he ate them up, and ate up Liebrandt when he was in the AL. But there are numerous others you can choose from.

I think Belichick wins as much as he does not because he’s a genius, but just because he’s not an idiot. Belichick schemes so that the other team’s best players don’t beat him. Here Carroll/Bevette had the chance to let a Wilson/Beast combination do exactly that, and they obsessed about having the maximum number of plays at their disposal instead of focusing on running the best one.

And don’t even get me started on Carroll’s handling of the clock that whole final drive.

It does seem to me, though, that “having the maximum number of plays at their disposal” was a quite defensible priority for Carroll and Bevette, given that it might be the single factor that would most maximize Seattle’s chances of scoring there. I don’t think the risk of an interception there was that much higher than that of a fumble on a handoff. But the likelihood of scoring on one of three plays there, rather than two, does seem meaningfully greater. I’m no football expert though — I think this is the one game I watched more than a few minutes of all season.

Has anyone else EVER seen an interception on a one-yard slant (not a deflection-pick, but a jump-the-route in .8 seconds pick)? I have not.

Birtelcom,

I just wrote a long reply to you that was eaten. Aaaagh. Don’t have time to rewrite it. Suffice it to say that, yes, you’re right, having the maximum number of plays at their disposal is a defensible priority. In fact, they should have ensured it. It could have been easily arranged. Lynch was tackled at the 1 with 1:06 remaining. It would have been very easy to run three plays – even running plays – in that amount of time with one time out. (Remember: they went 80 yards in like 50 seconds right before the half, in a sequence that included two running plays.) But they operated at cross purposes. They wanted BOTH the maximum number of plays and to run time off the clock. To try to get both they inserted an ill-advised play that did not suit their personnel, and it backfired spectacularly.

At least Mike Martz can rest easier now. The clown job he did on the sidelines in the 2001 SB has now been eclipsed.

Voomo,

In the Pittsburgh-Arizona SB a few years back, LB James Harrison had a 99-year pick-six on a Kurt Warner goal-line pass just before halftime. Can’t remember if it was a slant but it was a similar type instant-read throw, and he stepped in front of it and lumbered 99 yards for the TD.

Here it is:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RqnQwKAI4OE

Wow, hunh. It actually WAS a slant, though it didn’t develop quite as quickly as the ‘Hawks play and it was from the 2 yard line. And it was the last play of the first half. If Harrison gets tackled one yard from the end zone, no points for the Steelers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RqnQwKAI4OE

tag,

-Seattle had to run it on either 2nd or 3rd down because you can’t run it three times in 20 seconds with only one timeout.

-2nd down was a better choice for the pass because you force NE to play for both the pass and the run on 3rd down. If you run on 2nd down and get stuffed, you HAVE to pass on third down since you used your timeout already.

-Seattle switched to the pass because NE was playing for the run.

Voomo,

-QBs this year from the 1 yd line threw 66 TDs. Wilson’s INT was the first this year.

-Marshawn Lynch from the 1 this year only scored on one of five runs.

I’m one of those who thought it was definitely a bad call, but I’m having second thoughts, mainly from the “maximize your plays” argument.

I’m not impressed by the lack of interceptions from the 1 yard line. How many of those plays were anything like this situation? — where you *must* get a touchdown, and the game clock is running near 30 seconds.

I’ll add that Wilson has never thrown a meaningful TD from inside the 10 with less than 9 minutes left:

http://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/W/WilsRu00/touchdowns/passing/

But, I think bstar’s original point is right: The call wasn’t the main thing; it was the play of Butler, Wilson and Lockette.

John, bstar,

The maximizing your plays was entirely possible, but Carroll blew even that. As I said above, Lynch was tackled at the 1 with 1:06 left. With one time out left, Seattle can easily run three plays – even three running plays.

I suspect what happened is that when Lynch made it to the 1, Carroll expected Belichick to save time for his offense and call time out. (Which is what he did in his previous SB loss against the Giants.) But hoodie didn’t oblige him, probably because it didn’t work out then and he didn’t believe it would work out now. (NE is not GB – they can’t quick strike down the field: they don’t have a Nelson or Cobb, and Brady no longer throws long well. They are incredible efficient, but they averaged 5.9 yards per completion on the game – they have to dink and dunk.)

I think Carroll got discombulated by Belichick not calling time out. Again, terrible coaching. You can’t be basing your strategy on what you think the opposing coach will do with his time outs. So the clock wound down to under 30 seconds.

Or maybe , to take a charitable view, Carroll wanted the clock to wind down since he’d been burned by Rodgers and GB in the previous game, which had forced OT. But your priority at that point has to be to get the lead. Everything else is secondary. Once you let the clock wind down, you limit yourself a bit. (Though of course had Seattle not blown a TO a minute-and-half earlier near midfield, they would have had two TOs and could have done exactly what they wanted.)

I’ll just say this. NE finished 30th in the NFL against the run in short-yardage situations this season. Belichick built his defense to stop the pass. Lynch had run 24 times in the game and had gained at least 1 yard 22 times. Yes, they were facing a short-yardage package, but NE’s short-yardage goal-line defense is not Detroit’s. It might have been a knee-jerk reaction on the part of the public to howl that they should have run the ball, but it was not wrong.

Voomo,

To respond to your original post that started the diversion: advanced thinking in football tells you to take risks based on expected points. I’m at work and don’t have the numbers at hand, but going for a first down on fourth-and-goal on the eight yard line is not optimal at that point in the game.

Let’s say you eke out the first down. You still have first-and-goal at the seven or six-and-a-half yard line. Scoring a TD from there is anything but guaranteed (of course some teams are much better at this than others – I don’t know Seattle’s figures off the top of my head). Whereas if you go for it at the one (during the normal part of the game), even if you fail you have the other team backed up at the doorstep of the end zone. You limit their play calling options and, with a good defense, can often force a three-and-out and a punt from the endzone, receiving the ball back in favorable field position.

This situation can be debated and your point is a good one. But I tend to follow expected points in this regard. Now if you have NE’s offense, which executes incredibly well in the red zone, I would go for it every time. Brady is bound to find one of those 12 third-down white guys they inevitably send out on patterns to pick up a couple yards and the first down.

Sorry, I meant fourth-and-one at the eight yard line.

Sorry, I meant going for a first down on fourth-and-one on the eight yard line.

tag, I understand and agree with your analysis.

-in most situations.

Vs the Patriots, however, I throw that book out the window.

Several reasons.

One, as you said, if you have NE’s offense you would go for it every time. This means that you have to match NE score for score.

Yes, Seattle has a great defense, and maybe they make a big play. But given the same number of scoring opportunities as your opponent, you have to match them in terms of capitalizing.

Against New England, this means 7 points, not 3.

You are leaving 4 points on the field because you are not confident in gaining 1 yard.

And I only brought this up because of the hullaballoo around the final play. The “why didn’t they give it to Lynch?”

I ask the same question on 4th and 1 from the 8.

And no, getting that 1st down doesn’t guarantee a touchdown.

But you have 5 opportunities (4th, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th) to gain 8 yards. Go for it!

Tag and Voomo –

I posted something this morning (twice actually) but it’s not appearing anywhere. Anyway, the expected points calculators all show that Voomo is correct. Going for it in that 4th and 1 situation leads to more expected points than taking the field goal.

Voomo and David P,

I think players would love playing for you, Voomo. You’d just have to convince management not to kick you to the curb after those decisions backfired. 🙂

But, as David P makes clear, your thinking is sound. I haven’t been a coach since the ‘90s and have forgotten all the expected points calculations. I thought I’d remembered that somewhere around the 8 or 9 yard line, it’s a wash going for it on fourth-and-one vs. taking the FG, but evidently not. I think I’ve absorbed my experience from my former football team’s failures in this regard. We almost never scored a TD with first-and-goal anywhere outside the 7 yard line. On the 11 or 12, no problem. I tried everything – even trick plays – but little worked.

BTW, as a basketball player (I was at the end of my career here when I started coaching FB), I hated punting. Just giving the ball up like that. So by my final year of coaching, my team never punted. We always went for it on fourth down, no matter where we were on the field and no matter the yardage we needed for a first down. It paid off enormously. I read a few years ago that a HS football coach in Texas did the same thing and won state in his division, going undefeated.

tag-

You would have an incredibly difficult time in adapting to rugby then since the higher up the skill level/quality of play ladder you go the more likely a team is to punt the ball away before even a single tackle is made.

At the college level that I played at where the vast majority of players only had an American football background like I did most of us had a really difficult time with that concept.

tag, for me it is a question of thinking objectively Vs acquiescing to group-think.

We see this in baseball all the time.

Managers do things a certain way because That Is The Way Everybody Does It.

For example: using your best relief pitcher for only one inning. And only with a lead.

(Okay, many pitchers are conditioned to only throw for one inning, fine. But leave Kimbrel/Chapman/Rivera on the bench in a tie game on the road in the 9th inning?)

Just. Plain. Stupid.

But this is the way it is done.

Because this is the way it is done.

30 years ago that was insanity.

And i hope it will be once again be regarded as such sometime sooner than later.

A little late to the discussion, but I would nominate the 1958-1962 SF Giants for the discussion of the most impressive young talent debuting in a short period of time. I know it’s four players and not five, but you’ve got:

1958 – Orlando Cepeda

1959/1960 – Willie McCovey

1960 – Juan Marichal

1962/1963 – Gaylord Perry

This in additional to (IMHO) the greatest all-around player ever in Willie Mays, and some good complementary players such as Tom Haller, Jack Sanford, and Jim Davenport. How did they not win more than one pennant?

Lawrence Azrin:

And I believe they traded a boat load of talent. I believe Leon Wagner, Jackie Brandt, and Willie Kirkland (amongst others) sure would have made for a crowded OF (with the Alou’s as well). How about Bill White? They sure could have used some capable middle infielders….

Lawrence — Good point on those Giants. Measuring for age 27 or younger, there are 15 teams who had four 50-WAR men, and four of them are the Giants from 1962-65.

But those four guys — Perry, Marichal, McCovey and Cepeda — never had big years all at once — partly luck, partly because Perry had kind of a slow start, partly because Cepeda and McCovey were both first basemen at heart.

Perry’s first good year was ’64, so let’s start there:

1964 — McCovey slumped to replacement level.

1965 — Perry slumped near replacement level, and Cepeda missed most of the year with a knee injury.

1966 — Big years from Marichal, Perry and McCovey, and the last monster year by Mays. But they traded Cepeda in May for Ray Sadecki, who was also coming back from injury; Cepeda recovered, but Sadecki was brutally bad the rest of that year.

1967 — Sadecki was decent (though not enough to salvage the trade, with Cepeda winning MVP). Marichal slumped and missed some time. Mays had his worst year since the Korean War.

In each of those years, the Giants won 90-95 games, and three times missed the flag by 3 games or less.

I think their indecision on Cepeda and McCovey rippled through the whole lineup for much of that decade. Neither was suited to play outfield, but after McCovey’s ’59 ROY, they kept both players until ’66, after Cepeda got hurt. Failing to resolve that logjam compounded the problem of all the excess corner talent they produced in that decade. Matty Alou hit .301 in about 400 ABs spanning age 22-23, but never won an every-day job in the next 3 years (and hit poorly when he did play, perhaps related). They dumped him on Pittsburgh for almost nothing, and for the next 4 years he hit from .331-.342. They got some good years from Felipe, but didn’t get a good return when they traded him, and he still had a lot left.

@40/JA,

I understand what you mean about the early/mid-60s Giants having one too many first basemen, but if I had two hitters as great/dominant as McCovey and Cepeda were, I’d be extremely reluctant to depart with them too.

They certainly made the right long-term decision in keeping McCovey.

Malcolm Butler of Hinds Community College made a brilliant play.

Perfectly timed in every way.

I think it was a actually a smart play call.

As a sidebar, he redeemed fellow Hinds product Leon Lett for previous Super Bowl ignonimity in spectacular fashion.

Later, as an undrafted free agent from directional (west) Alabama, he stands forever as a testament to the genius of Bill Belichick, the short-tenured “HC of the NYJ.”

I don’t think Andruw Jones is an unreasonable selection. But I do believe it will take decades and would require the VC peopled with a “friends of Andruw Jones,” conglomerate of Glavine, Maddux and Smoltz.