This is the third in a series of posts on the 1890s Baltimore Orioles by HHS contributor e pluribus munu. if you’ve written something you’d like to share with the HHS community, drop me a note at doughhs@hotmail.ca.

In 1897, Oriole manager Ned Hanlon was quoted in The Sporting News, saying: “We didn’t play ball in 1889 as we play it now.” Although the pitching change of 1893 had been made midway in that eight-year interval, the article went on to specify something entirely different as the point of Hanlon’s remark. “In the old days, once a man got to first base the next batter walked to the plate and promptly attempted to knock the cover off the ball.” By 1897, however, teams were increasingly playing what was called “scientific baseball” or “inside baseball”: they were focusing on complex one-run-at-a-time tactics that required hitters to execute their at-bats in support of team strategies, rather than swinging away to try to build up their individual batting records.

I don’t know of any reason why a baseball person in, say, 1905, might have said, “We didn’t play ball in 1897 as we play it now.” The leagues in 1905 were much different from those in 1897, but the game was basically the same. “Inside baseball” continued to be thought of as the “modern” game until Babe Ruth and the Lively Ball era ushered in a dramatically new style of play, one that we might see as setting the norms of the game for as long as forty years, until the 1960s swing towards pitcher dominance produced a richer hybrid of the strategies of the Dead and Lively Ball eras. (I’m using the term Deadball Era a bit loosely. The transition period of 1899-1901, including the creation of the AL, produced a few atypical seasons. The Deadball Era is usually dated from the return to late-1890s norms, about 1902-3, through the years of even weaker offense, ending in 1918 or 1919.)

The premise of this series of posts is that the tradition of regarding the “modern era” of baseball as beginning with the 1901 creation of the AL is historically misguided, and that our own Circle of Greats has made an error in using that milestone as its qualifying period (although a reasonable error, since the original goal was to replicate the assumptions of the BBWAA Hall voters, who were largely responsible for that historical narrative). In fact, the game’s “Rubicon”, the dividing line between early and modern baseball, was crossed in the early 1890s. At that time, changes that had been gradually building led to the sudden rise and dominance of the Old Baltimore Orioles, a team embodying the systematic adoption of those new, “modern” trends, and establishing new baseball norms that would last for a quarter century. That Ned Hanlon’s “scientific” baseball had become the respected standard of the game is evidenced by the initial reaction to the Babe leading the majors into a new era of free-swinging; many stars of the preceding period were appalled, as the 1880s style of trying to knock the cover off the ball had come to be seen as primitive and unworthy of “scientific” major league professionals.

The Rise of “Inside Baseball”

“Modern” baseball – that is, the baseball we associate with the early 20th century – emerged gradually. I don’t know enough to outline a detailed history, but it seems clear that in the mid-1880s, Charlie Comiskey’s American Association St. Louis Browns exemplified a number of “modern” traits. Those teams were associated with revival of the bunt hit and a fundamental emphasis on superior fielding (as well as raucous rowdyism, prefiguring the Orioles). However, the Browns became so dominant over other AA teams that it may be that the contributions of small-ball elements did not stand out to contemporaries. In the late 1880s, a respected manager, now forgotten, named Gus Schmelz, built a small-ball strategy for his clubs that featured aggressive use of the sacrifice bunt (it was no secret as The Sporting News ran multiple columns on the “Schmelz System”). But Schmelz’s teams generally had mediocre or poor talent; he may have gotten the best out of those teams, but the success of his “system” was modest.

It’s common to view Frank Selee, the manager of the Boston Beaneaters from 1890 to 1901, as the first “modern manager,” a team leader who put a comprehensive strategy of “inside baseball” together. Selee was a terrific manager, the architect of the great Cubs teams of the 1900s (Selee fell ill from tuberculosis in 1905, the disease that claimed his life four years later, so his protégé, Frank Chance, got to harvest those fruits). But, before Chicago, Selee’s Beaneaters won five pennants during the 1890s. I think that if we’re looking for a “First Modern Manager” candidate, he’s a good choice.

Selee adopted the “Schmelz System,” though in much greater depth, going beyond bunt strategies to emphasize bat control, base-running, and well drilled execution on offense and defense. Players had to master the hit-and-run and the outfield cut-off throw (a Selee innovation) while being drilled in other fielding skills, resulting in teams that were consistently at the top of the fielding stats. The Beaneaters won pennants in ’91, ’92, and ’93 (though the first was tainted by rumors of games thrown to deny victory to Chicago and its anti-union manager and owner, Cap Anson), and in two of those years they led the league in the small-ball stat of ~BBIP (explained in earlier posts and calculated as ~BBIP = (BB+SB+HBP+SH)/PA)). If Ned Hanlon had a model when he turned the Orioles into a small-ball club, it was surely one established by Selee.

But Selee managed a team that should have won pennants. Boston was one of the perennial powers of the NL, a league that did not have a history of upwardly mobile upstart teams. Selee’s teams featured terrific rosters, anchored by the greatest pitcher of the decade, Kid Nichols (297 wins and 98+ WAR in the ‘90s alone). Other teams surely saw the approach Selee was emphasizing, but likely would have been intimidated by the Boston rosters, whatever their style of play.

Hanlon’s Orioles were different. Although many of his players became stars as the team rose to dominance, the Orioles’ were initially a team of nonentities (with the exception of one year with an aging Dan Brouthers aboard). Hanlon and his methods appeared to have transformed them: for inside baseball, the Orioles’ success was proof of concept. My basic claim is that this is what boosted the prestige of inside baseball and led to widespread adoption of its methods.

The “Modernity” of Hanlon and the Orioles

Examining some contrasting features of Selee and Hanlon, we can measure the degree to which we might consider each to be “modern” in a more expansive sense. Over the course of 1891-1900, Selee and Hanlon each managed five pennant-winning NL clubs (the only partial break in their dominance was in the split 154-game season of 1892, when Patsy Tebeau’s Cleveland Spiders, led by Cy Young, posted the best record in the season’s second half, thereby earning the right to be whitewashed in a postseason series with the Beaneaters). Both Selee and Hanlon prevailed using small-ball strategies. But their managing styles were nevertheless very different.

Selee was a conspicuous believer in baseball as a gentleman’s game: when it came to Beaneater players, no ruffians need apply. He could say, “It was my good fortune to be surrounded by a lot of good, clean fellows who got along finely together. To tell the truth, I would not have anyone on a team who was not congenial.” To follow such a criterion in the hard-drinking culture of 1890s baseball placed an enormous handicap on the Beaneaters, but Selee made it work. He was admired for his intelligence, diligence, and honesty, and was clearly a terrific manager of men, in addition to being first rate in technical command.

But, where Selee’s technical command was “modern” and his exemplary leadership style adhered to traditional values, Hanlon was utterly different. His earliest managerial job came with the 1891 Pittsburg club; it was not a success and Hanlon was soon gone. But, during his short tenure, Hanlon was so unscrupulous in using devious means to plunder contracted players from other teams that his mark remains on the Pittsburgh team to this day: Hanlon was the “Pirate” that became the team’s nickname starting in that season (making fun of complaints by the Philadelphia Athletics that Pittsburg’s acquisition of A’s star player Lou Bierbauer was “piratical”).

When Hanlon came to Baltimore, he not only hired ruffians, his team became famous for successful cheating, on-field confrontation, and umpire intimidation, all in the service of unnerving opponents and making them easier to beat. As a team executive, Hanlon used the desperation of Orioles owner Harry von der Horst to bargain for exceptional control over team decisions when he signed on as manager; a year later, he bailed von der Horst out financially in return for the title of Club President and full general manager authority (at League meetings, von der Horst wore a pin that read, “Ask Hanlon”). He built the team acquiring players on his own initiative, and was so shrewd in his dealings that he earned the nickname “Foxy Ned.” Hanlon was as good or better than Selee as a student of the emerging modern game, but he was clear about the bottom-line value of his efforts: “I decided early in the game that there was money to be made in baseball if it was studied seriously. After I took hold of the Orioles, I often got out of bed in the night to jot down a play that might be worked out.” His playbook produced results, and, indeed, baseball made him a very wealthy man.

In 1899, Hanlon was the driving force behind the brief and corrupt emergence of “syndicate baseball”, the control of multiple clubs by a single ownership group. He negotiated a deal whereby Baltimore would consolidate with the Brooklyn club, shifting resources from the smaller city to New York in order to maximize total attendance revenues. Hanlon himself moved north to manage the Brooklyn team, which was renamed the Superbas, because “Hanlon’s Superbas” was the well-known name of a popular vaudeville troupe (Hanlon is the only man I’m aware of to have two teams named after him). He persuaded the Orioles’ principal owner von der Horst to go along with this arrangement, and on the Brooklyn side, the new partners were explicit in stipulating that, as in Baltimore, Hanlon’s authority in matters pertaining to personnel and daily team management would be absolute. After transferring Baltimore’s better players to the Superbas, Hanlon won pennants in his first two years in Brooklyn.

Frank Selee may have been the first modern manager in terms of his commitment to inside baseball, but Ned Hanlon and the Orioles embodied a much broader scope of baseball modernity in methods and values, the latter to a degree incompatible with Selee’s admirable traditionalist character.

Forestalling the “Era of the Hitter”

Before concluding this series with a section on the legacies of Ned Hanlon and the Old Orioles, I’d like to step back and look a bit more globally at the major theme that introduced the initial post: the transience of the impact of the 1893 pitching changes. My goal here is to sort out the causes that may be directly tied to the rise of inside baseball and the influence of men like Selee and Hanlon, and other factors that may have been essentially independent of them.

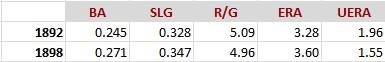

The 1893 pitching changes were intended to rebalance baseball to the advantage of the hitter, and for a brief time this was the result. However, as we have seen, that interval lasted no more than five years. By 1898, offense had fallen below 1892 levels: although batting and slugging averages were still considerably higher than before the pitching change, teams were averaging fewer runs per game. This does not seem to have been a matter of pitcher improvement over  1892: ERA levels were still significantly higher in 1898. Rather, the drop in R/G seems to be attributable to a sharp decrease in Unearned Run Averages (UERA), reflecting major fielding improvements.

1892: ERA levels were still significantly higher in 1898. Rather, the drop in R/G seems to be attributable to a sharp decrease in Unearned Run Averages (UERA), reflecting major fielding improvements.

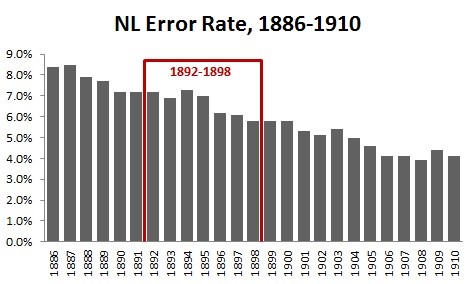

As we have seen in the cases of the Beaneaters and Orioles, mastery of inside baseball tactics entailed high standards of fielding excellence. The Orioles went from the worst fielding team in the league in 1892 to a record-tying (I think) fielding average of .944 in 1894, topping that mark by two points the following season. While Selee’s Bostons led the league in DER five times in the decade 1891-1900, the Orioles’ DER over the 1893-1900 period was even better than the Beaneaters. But, it wasn’t just the leading clubs, as improved fielding became a league-wide phenomenon. Apart from a brief bump in the Error Rate in 1894 and a residual effect the following year (the possible cause for which I won’t argue here, having done so in previous comments), the years after the 1893 pitching change saw the continuation of a long-term trend of improvement in fielders’ ball handling skills.

Between 1892 and 1898, the league-wide error rate decreased almost 20%. The combination of the growing prestige of inside baseball’s one-run strategies, and its focus on fielding skills, were probably the two biggest factors forestalling any long-term effects of the ’93 pitching change on the balance of the game.

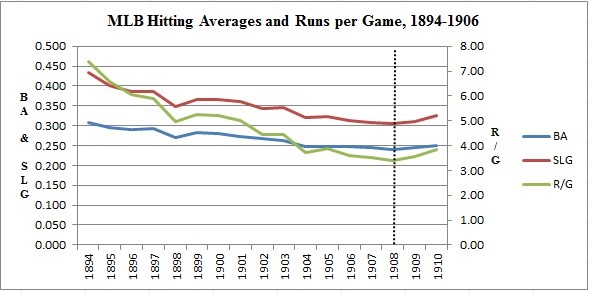

Ironically, the inside baseball of the 1890s led – after a short period of disruption as the NL regrouped and the AL suddenly expanded the talent pool – to a period of depressed offense, with batting stats and R/G well below pre-1893 levels. The following chart illustrates the fall-off in these categories from their 1894 peaks to a nadir in 1908:

I believe we are seeing two distinct stages in this trend. The initial decline after 1894 seems to me to be the product of one-run inside baseball and the defensive improvement already identified. But a second significant drop a decade later may be connected to changes in pitching that began with the new century. The early 1900s was an era of pitching innovation, with dramatically effective new deliveries being introduced by young stars, such as Christy Mathewson (the fadeaway/screwball, 1901), Jack Chesbro (the spitter, 1904), Nap Rucker and Eddie Cicotte (the knuckleball, 1907/8), and others (the emery ball, the shine ball, etc.). (I have to credit Peter Morris’s Game of Inches for alerting me to the timing of these innovations.) These new pitches often involved illegal doctoring of the ball, but they were effective, and they seem to have been a key factor in ushering in the true Deadball Era, just a decade after the greatest of hitting years. With increasing numbers of pitchers learning to add one or more of these deliveries to their repertoires, innovative pitching ultimately joined improved fielding in erasing all traces of the advantages hitters received from the 1893 move to 60’6”.

I don’t think this second wave of defensive adjustment can be directly connected with the rise of inside baseball and the Old Orioles, but should rather be seen as magnifying the effects of their influence.

Hanlon’s Legacy and John J. McGraw

In his book on baseball managers, Bill James begrudgingly acknowledges that Ned Hanlon established the single most dominant lineage of managers in Major League history. It is obvious, of course, that the outstanding managerial career of John McGraw, Hanlon’s protégé, is seen as a facet of Hanlon’s legacy, but James – who does not like Hanlon – lists him beside historic managers such as Miller Huggins, Frankie Frisch, Leo Durocher, Casey Stengel, Earl Weaver, Billy Martin, Tony LaRussa . . . The list is enormous, far overshadowing other important managerial “lineages,” such as those of Frank Selee and Connie Mack, and other sources echo James’s judgment. In my view, this type of assessment is interesting, but misses the main point: Hanlon and the Orioles influenced all managers by validating the new “inside baseball.”

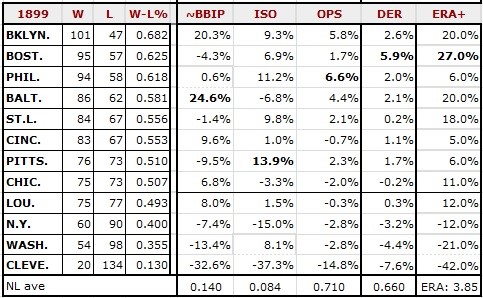

Nevertheless, it is hard to avoid the judgment that Hanlon’s impact on baseball was greatly magnified by the role John McGraw went on to play, and McGraw’s style of managing, while ultimately changing with the times, was clearly anchored in Hanlon’s approach. Consider, for example, the records of NL teams in 1899, the year of syndicate baseball:

Hanlon was managing Brooklyn, having taken along with him the greater portion of the Orioles’ best talent, and as we might expect, Brooklyn had been transformed in the Hanlon mode – here are the team’s 1898 numbers for contrast:

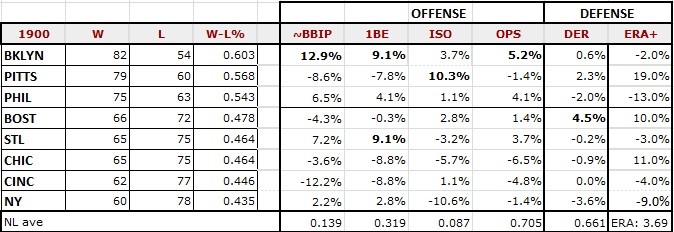

Brooklyn’s ~BBIP went from the lowest in the league to twenty percent above league average, as Hanlon’s discipline and the Oriole refugees brought Brooklyn a pennant as a small-ball team. But for the first time since 1893, Hanlon’s team did not lead the league in ~BBIP: it was his old team, the Orioles, who continued to excel in that category, even though inside-baseball stalwarts like Willie Keeler and Hughie Jennings were now in Brooklyn. The reason is that Brooklyn/Baltimore co-owner Hanlon (unwillingly?) left 26 year-old McGraw in charge of the Orioles and, despite a roster only half-Oriole in background, McGraw’s managerial leadership resulted in a genuinely Oriole team profile. More convincing evidence of the start of a legacy would be hard to find – but it exists. Consider the eight-team NL in 1900, Baltimore having been dropped from the league along with three unsuccessful franchises (two were Baltimore’s AA brethren Senators and Colonels, while the last was the unfortunate Cleveland club which died after switching identities with its syndicate partner, the fourth AA survivor and formerly disastrous St. Louis Browns, now renamed the Cardinals):

In this chart, I’ve included the stat category 1BE (One-Base Events: ~BBIP plus singles), because the Cardinals, in 1899 a league-average team in this category, have somehow been able to challenge Hanlon’s Brooklyn Superbas in this typically small-ball category. The reason is because McGraw had joined the Cardinals, along with Oriole refugees like Dan McGann, and they drove the team stats in a Hanlonesque direction (while driving the very non-Hanlonesque Cardinals manager, Patsy Tebeau, permanently out of baseball at midseason).

This seems to follow the story line, that Hanlon’s legacy begins with his disciple McGraw, but I think the reality was actually more complex and interesting. When Hanlon first inherited McGraw as a 19 year-old, he recognized McGraw’s talent, but needed his roster slot for a more mature player. He proposed sending McGraw to the minors on a “farming” contract, ostensibly so McGraw could get in more playing time. But McGraw dug in and eventually managed to change Hanlon’s mind. One factor may have been that Hanlon observed McGraw taking batting practice and hitting consistently to the opposite field. He asked McGraw who had taught him to do that and McGraw said that he’d taught himself: it allowed him to cross up any defensive shift the opposition adopted when he came to bat. According to one account (from the old sports writer Fred Lieb), this left a major impression on Hanlon: McGraw had been practicing Hanlon’s strategy of striving to confuse the opposition before Hanlon arrived to preach his new doctrine. In a comment on my last post I went into detail about another exceptional example of McGraw’s role: how it was that over the winter of 1893-94 McGraw, not Hanlon, transformed Hughie Jennings from a hopeless hitter (.241/.290/.301 thru 1893) into one of the best in the league (.335/.411/.479 in 1894, and .361/.449/.474 for 1894-98). This is another example of McGraw’s precocious appreciation of baseball methods and his leadership abilities.

There is no question that McGraw learned an enormous amount from Hanlon. Connie Mack, who played under Hanlon in Pittsburgh, said, “I think it’s safe to say [Hanlon] knew more about baseball than any other man of his day. And he knew how to teach the game to young players. He talked about it from morning until night, on the bench, on the field, in hotel lobbies, at meals, aboard trains. . . .” But no one seems to think Hanlon was much of a field general. He infused his players with baseball knowledge and was relentless in demanding they master the skills, but then he left it to them to implement these lessons as they saw fit in game contexts. Perhaps, then, it is not surprising that, at least in Bill James’ analysis, McGraw’s profile as a manager was similar to Hanlon’s in this respect, despite their differences in temperament.

McGraw seems to have been on track to become a baseball leader and mastermind as a teenager. Hanlon certainly was a mentor to McGraw, and he clearly arrived in Baltimore with his unusually large ambitions already set. However, the highly idiosyncratic team profile that emerged as the Old Orioles clearly reflected the character of its ruffianly spark plug to an unusual degree. Hanlon appears to have decided early to give the kid his head, and to make sure that in designing his ideal team, he kept it a good fit with McGraw.

Given McGraw’s enormous influence on both leagues during the early part of the 20th century, perhaps instead of seeing McGraw and the teams he managed as the most prominent immediate legacies of Hanlon and the Orioles, we should see Hanlon and McGraw as authoring a joint legacy from the beginning.

I’d like to thank Doug for suggesting I think about writing up these ideas and for offering to upload them as HHS posts. Doug did some careful editing and formatting, and he is responsible for inserting all the many links to the B-R pages of players and managers, making these posts much more useful.

Although I was uncomfortable about writing so much on the basis of initially (and maybe ultimately) knowing so little, in the end this was a lot of fun for me, and I’d encourage everyone to think about taking Doug up on his suggestion to write him about any idea for a post or series you might want to undertake. I’d bet even 20th and 21st century topics might generate interest!

It was my pleasure to post your articles, epm. You illuminated so much that I didn’t know about the 19th century game.

First off, you wrote this series well. I read every word, which is extremely rare.

Now, you mentioned the improvement of fielding from 1889-1897. One thing that certainly helped this was in increasing use of gloves by players. Bid McPhee was a phenomenal fielder. Made the HOF on his fielding (although, granted, it took baseball only 100 years to put him there.) He didn’t wear a glove until late in his career, the 1899 season. That’s not to say he was a bad hitter – .272/.355/.373 is good, but it won’t get you into the HOF. Most players in 1889 didn’t wear gloves. Most if not all wore them 8 years later, and that IMHO is the main thrust in the improved fielding.

Maybe there’s a topic for your next post/series. I’d write it, but like I said in a comment to your 1st post, I simply don’t have the time.

You’re certainly right, John. The use of gloves was a key factor in improving fielding, but I’m not sure that’s the same issue as the one that The Sporting News read into Hanlon’s comment, which concerned overall hitting strategies.

By the time of the Orioles, Bid McPhee was already a rare oddity, and according to Bill James, he actually picked up the glove in 1896, ending the last remnant of the gloveless era (except for a few pitchers). So the proliferation of glove use probably had little impact during the post-1892 period under discussion here. (According to Peter Morris, fielders’ gloves began to become the norm from the mid-1880s.) I did wonder whether the sharp improvements after 1892 might have to do with growing glove size. In 1893, that may have been the case, but in 1894, the NL placed a strict limit on glove size, allowing only catchers and first basemen to wear larger gloves (this comes from Morris’s book too). So overall, I think the major impact of gloves on lowered error rates probably peaks before 1894.

As a related thought, it struck me while writing that I’ve always thought of fielding in early baseball as sort of “primitive” because of the high error rates. But thinking about the skill involved in playing Major League ball without a glove, I suspect that in some respects we have never seen fielders as skillful as those back in the 1880s, at least in terms of pure ball handling (not in terms of position play, which I think is at its historical peak today and still improving). If those 19th century guys were given a few months to get used to today’s gloves, I bet they’d be terrific ball handlers by modern standards, but if today’s players had to go back in time and play without gloves, I suspect many would look for another profession — I think barehanded play is something you’d need to become skilled in gradually from youth.

And thanks once again for your kind words. They encouraged me with each installment.

Another factor in reduced scoring (though, not necessarily reduced errors) was the innovations of different players in fielding practices. One example is Bobby Wallace, credited with perfecting the skill of fielding grounders and throwing in a continuous motion (as opposed to stopping, setting oneself and then throwing). The story goes that Wallace developed this approach after observing the high number of times the batter just beats the throw to first, despite the batted ball being fielded cleanly.

A really good point, Doug. Wallace’s innovation would be part of what I’d call “position play,” rather than “ball handling,” and the widespread of improvement in position play would be reflected in DER (percent of balls in play converted to outs), rather than Error Rate. Wallace didn’t give a date to his innovation, but since he didn’t play infield regularly till 1897, it would be after that date. Of course, we can’t track the influence of any one innovation, but we can see a sharp rise in DER taking place from 1904 through 1908, tanking suddenly in 1911 (a hitter’s year), and then returning to 1908 levels by 1918 before tanking as the lively ball comes in. Here are the MLB figures from 1892 to 1921:

1892 .672

1893 .654

1894 .626

1895 .637

1896 .649

1897 .648

1898 .669

1899 .669

1900 .660

1901 .661

1902 .661

1903 .672

1904 .691

1905 .690

1906 .695

1907 .697

1908 .707

1909 .697

1910 .690

1911 .673

1912 .672

1913 .688

1914 .690

1915 .697

1916 .701

1917 .704

1918 .706

1919 .697

1920 .685

1921 .677

(For reference, the figure for 2017 was .688. I thought I’d look at 1968 as a modern “dead ball” season: DER was .715.)

Of course, DER measures more than position play and ball handling by fielders: it reflects how well pitching is keeping batters from solid contact and so forth. I interpreted the rise in DER in the period 1903-8 as a reflection of pitching innovation, but that was speculative, and even if true, certainly oversimplifies the case. Your comment illustrates that.

By the way, does anyone understand the 1911-12 batting surge? I remember reading about it, but don’t recall if there was an explanation for it. OPS went from .644 in 1910 to .693 in 1911, and then to .695 in 1912. It falls to .670 in ’13, and, after the Federal League screws up the stats for two years, it’s at .638 in 1916. Almost like a replay of 1892-98 . . .

I asked at the end of the comment above, “Does anyone understand the 1911-12 batting surge?” Poking around online. I encountered an answer on the not too hifalutin website known as Wikipedia. An article there links the hitting boost to the introduction of the cork-centered ball. A detailed discussion in Peter Morris’s book supports this with thorough documentation: the ball was introduced, with fanfare, in May of the 1910 season (though it is unclear how widespread the introduction was), and was not only livelier, but retained its shape throughout a game. The leagues voted before the 1911 season to make use of the new ball universal. (The ball was modified again in 1925, though it was intended to be a neutral change in so far as hitting is concerned, simply adding to the endurance of the ball — hitting nevertheless leaped.)

The subsequent hitting decline from 1913 is attributed by the Wikipedia authors to further expansion of the pitching arsenal through the emery ball and related doctored balls. The same article disputes the notion that the ball became more lively after 1919, and instead attributes the resurgence of hitting to the banning of the spitball and other doctored-ball deliveries. It also notes (but does not endorse) the possible effect of Babe Ruth’s success as shifting prestige from small ball to slugging (an idea parallel to my argument about the effects of the Orioles and inside baseball).

Picking up a related thread, given that we have here two documented cases of new balls being introduced (1911 and 1925), I thought I’d take a look at the effects, if any, on Error Rates. I looked at the period 1908-1930, and the results are unfortunately pretty inconclusive. In 1909 there was a very sharp increase in E-Rate of 6.38% (the actual E-Rate went from 4.08% to 4.34%), for which I know of no explanation. Otherwise, E-Rates drop continuously. Here are the seven exceptions to the general 23-season trend of declining errors and some possible explanations I can think of (or not):

1909: +6.38% (no explanation)

1911: +4.38% (new ball)

1914: +4.24% (talent thinned in AL/NL by addition of FL)

1923: +3.98% (no explanation)

1925: +8.36% (new ball)

1927: +2.85% (no explanation)

1930: +3.73% (no explanation)

(For 1914 and 1915, my calculations were for the AL and NL only.)

Excluding the 1909 jump, 1911 and 1925 have the largest increases, and that may support the theory that a new, livelier ball initially challenges fielders’ ball handling, though the 1909 exception makes this less convincing than it would otherwise be (1923 and 1930 are unhelpful too!). Note too that the 1925 change was not intended to create a livelier ball (unlike the change in 1911), though OPS did rise from .742 to .765, comfortably the highest of the era until the batting boom of 1929-1930 (I haven’t otherwise looked at the ’30s, except to note that hitting subsided sharply in 1931).

For reference, the jump in E-Rate from 1893 to 1894 that I’ve been making such a fuss about, and suggesting as the result of a changed baseball, was 6.97%. It should be obvious that I searching here for collateral evidence to support my hypothesis for that ’90s phenomenon. I didn’t find the smoking gun I was looking for, just a little more smoke.

Perhaps it should be mentioned that a new rule that went into effect in 1920 was that the umpires should frequently put a new ball into play. Prior to that the ball was kept in the game for as long as possible, balls hit into the stands were retrieved and put back into play. That resulted in balls being dirty, muddied, scratched, gouged, scruffed, lop-sided, etc. There were whole games played with a single ball. Part way into the 1920 season AL owners had complained to League President Ban Johnson that umpires were running up expenses by throwing out too many balls unnecessarily, so Johnson issued a notice ordering umpires to “keep the balls in the games as much as possible, except those which were dangerous”. Then in August, when Ray Chapman was killed by a pitch that was hard to see, umpires went back to changing balls frequently.

Good point, Richard. Once you begin to explore the cause behind some change in MLB stats, there always seem to be many, contributing in uncertain proportions.

Apropos of nothing in particular, 37 year-old Curtis Granderson today recorded a career best 6 RBI game. He’s the 55th searchable player that old with a 6 RBI game; scanning the list, I find that Jerry Grote, Damian Miller, Charlie O’Brien and Dode Paskert (and probably others) also set a new career best but, since it was surprising to see their names on the list (unlike Granderson), it’s not surprising they hadn’t previously recorded such a game.

Yes, and Brandon Crawford had 4 of the 5 Giants’ hits in a defeat of Scherzer yesterday – just off Billy Williams’ 4 out of all 4 Cubs hits in this one:

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1969/B09050CHN1969.htm

Not a bad day, despite the loss….

Reminded me of this game. https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHA/CHA196608160.shtml

Bert Campaneris went 4 for 4 (the rest of the team was 2 for 28) and scored 4 runs in an A’s 4-2 win over the White Sox (it’s the most runs in a game by a team having all of their runs scored by one player). Oh, and the A’s had zero RBI in the game, as Campy scored on an error by the third baseman (I think it was on an attempted pickoff throw from the catcher), on a wild pitch, on a passed ball, and from first base (!) on a wide pickoff throw from the pitcher.

Interesting/decent top of the order for the CWS with Buford, Agee, and Ward…..Always wondered if Tommy McCraw would have been a “hitter” at Coors Field and what, exactly, was he doing on a ML roster for all those years

Campy got it done on the basepaths and on D.

Highest career WAR with a Rbat under -70:

76.9 … Ozzie Smith

55.8 … Luis Aparicio

53.1 … CAMPY

45.6 … Omar Visquel

45.1 … Roger Peckinpaugh

42.9 … Rabbit Marinville

40.9 … Mark Belanger

40.1 … Dave Concepcion

A very interesting group, Voomo. Campy is not really like the others: his hitting, at -71 Rbat, is far stronger than the rest of the group, who range from -116 (Peckinpaugh) to -244 (Vizquel).

If you prorate Rbat, Rbaser, dWAR, and WAR per 1000 PA, their profiles are very diverse.

Campy is, of course, the “best” hitter, far less deep in negative territory: his Rbat/1KPA is -7.38; the others range from -10.86 (not Peck, when you prorate, but Smith) to -33.18 (not Omar, but Belanger: what a terrible hitter!).

The best baserunner turns out to be Aparicio, at 8.9 Rbaser/1KPA; the worst is Omar at -0.08. Actually, three in this group show virtually nothing as baserunners: Peck is at 0.84 and Rabbit at 0.36. Only three are really strong base runners: in addition to Luis, Ozzie is at 7.33 and Campy at 6.03.

On defense, as measured by dWAR, naturally Ozzie tops the . . . No, wait! It’s Belanger on top, by a lot: 5.98 dWAR/1KPA to Ozzie’s 4.10. On this measure, Campy comes in last in the group, at 2.19, though all six who are not Belanger or Ozzie are closely clustered (between 2.19 and 2.99).

Ozzie does lead in one category, though: WAR/1KPA. His 7.13 is far above the group average of 5.10. Only Belanger is remotely close to Ozzie, at 6.20.

I hadn’t remembered how weak Belanger was as a hitter: bad, sure, that I recall, but he was truly awful. About all you can say in support of his career season records are that they’re better than his post-season hitting stats. Yet his fielding is so strong that he entirely makes up for it: Earl Weaver seems to have known what he was doing.

An analysis I did for % of career runners driven in as of the end of the 2014 season for all searchable players with at least 6200 PA shows Belanger in last place out of 297 players.

Richard, I remember your multiple calculations of percent of runners driven in (%RDI) for 2017 (which readers will find near the end of this HHS string), but I don’t recall your sharing a career list. If you did, could you remind me where? (And if not, could you share the list here?) I thought your idea was one we should add into our thinking when we consider player value in general, but I have to confess I haven’t been following up.

Mark Belanger is clearly an example of a player of contrasting extremes. (One counter-example might be Dick Stuart for hitting/fielding; another Ernie Lombardi for hitting/baserunning.) I think it would be interesting to compile a list of players who were profoundly deficient in one major aspect of the game, but compensated with some profound strength that kept them in the line-up throughout a long career.

Here’s the list for % runners driven in. It is for players with 6200 PA and I did not count the batter as a base runner. I chose 6200 PA because they all fit on one page of a BR PI Split Finder result sheet. It is for the searchable era which is mostly 1973 to the present but there is a small number of players whose careers pre-date 1973, right back to Gil Hodges. As a reminder I did not count those PA in which the player received a BB or HBP except for the bases loaded situation.

%RDI Player

0.215 ….. Manny Ramirez

0.214 ….. Frank Thomas

0.213 ….. Miguel Cabrera

0.212 ….. Barry Bonds

0.210 ….. Albert Pujols

0.209 ….. Larry Walker

0.208 ….. Todd Helton

0.207 ….. Albert Belle

0.207 ….. Jeff Bagwell

0.206 ….. Carlos Delgado

0.203 ….. Mark McGwire

0.202 ….. Bobby Abreu

0.201 ….. Lance Berkman

0.200 ….. Keith Hernandez

0.200 ….. Juan Gonzalez

0.200 ….. George Brett

0.199 ….. Dante Bichette

0.199 ….. Mo Vaughn

0.199 ….. David Ortiz

0.199 ….. Will Clark

0.198 ….. Jason Giambi

0.198 ….. Vladimir Guerrero

0.198 ….. Kirby Puckett

0.197 ….. Adrian Gonzalez

0.196 ….. Edgar Martinez

0.196 ….. Matt Holliday

0.196 ….. Magglio Ordonez

0.195 ….. Mark Teixeira

0.195 ….. Jose Canseco

0.195 ….. Chipper Jones

0.195 ….. Alex Rodriguez

0.195 ….. Wally Joyner

0.194 ….. Moises Alou

0.194 ….. Andres Galarraga

0.194 ….. Mike Piazza

0.194 ….. Gary Sheffield

0.193 ….. Dave Parker

0.192 ….. Jim Thome

0.192 ….. Ken Griffey2

0.192 ….. Carlos Beltran

0.191 ….. Harmon Killebrew

0.191 ….. Harold Baines

0.191 ….. Mark Grace

0.190 ….. Carlos Lee

0.190 ….. Ted Simmons

0.190 ….. Aramis Ramirez

0.190 ….. Dick Allen

0.190 ….. Willie McCovey

0.189 ….. Al Oliver

0.189 ….. Don Mattingly

0.189 ….. Kent Hrbek

0.189 ….. Tony Gwynn

0.189 ….. David Justice

0.189 ….. Duke Snider

0.189 ….. David Wright

0.188 ….. Boog Powell

0.188 ….. Mike Schmidt

0.188 ….. Brian Giles

0.187 ….. Ryan Klesko

0.187 ….. Scott Rolen

0.186 ….. Chase Utley

0.186 ….. Paul O’Neill

0.186 ….. John Olerud

0.186 ….. Cecil Cooper

0.185 ….. Jeff Kent

0.185 ….. Frank Robinson

0.184 ….. Rafael Palmeiro

0.184 ….. Bobby Bonilla

0.184 ….. Eddie Murray

0.183 ….. Tommy Davis

0.183 ….. Sammy Sosa

0.183 ….. Larry Doby

0.183 ….. Greg Luzinski

0.182 ….. Tony Oliva

0.182 ….. Darryl Strawberry

0.182 ….. Paul Molitor

0.182 ….. Chili Davis

0.182 ….. Jose Cruz

0.182 ….. Jack Clark

0.181 ….. Raul Ibanez

0.181 ….. Tino Martinez

0.181 ….. Joe Carter

0.181 ….. Michael Young

0.181 ….. Fred McGriff

0.181 ….. Julio Franco

0.181 ….. Luis Gonzalez

0.181 ….. Tim Salmon

0.181 ….. Jim Rice

0.180 ….. Garret Anderson

0.180 ….. Miguel Tejada

0.180 ….. Ray Lankford

0.180 ….. Carl Yastrzemski

0.180 ….. Amos Otis

0.179 ….. J.T. Snow

0.179 ….. Gil Hodges

0.179 ….. Al Kaline

0.179 ….. Jeff Conine

0.179 ….. Bobby Murcer

0.178 ….. George Bell

0.178 ….. Reggie Smith

0.178 ….. Torii Hunter

0.177 ….. Bill Madlock

0.177 ….. Fred Lynn

0.177 ….. George Hendrick

0.177 ….. Andre Dawson

0.177 ….. Robin Ventura

0.177 ….. B.J. Surhoff

0.177 ….. Steve Garvey

0.177 ….. Mike Lowell

0.177 ….. Matt Williams

0.177 ….. Frank Howard

0.177 ….. Reggie Jackson

0.176 ….. Mike Hargrove

0.176 ….. Paul Konerko

0.176 ….. Ben Oglivie

0.176 ….. Dale Murphy

0.176 ….. Bobby Bonds

0.176 ….. Jim Edmonds

0.176 ….. Tim Raines

0.176 ….. Pat Burrell

0.176 ….. Andy Van Slyke

0.176 ….. Hubie Brooks

0.175 ….. Bernie Williams

0.175 ….. Ruben Sierra

0.174 ….. Ellis Burks

0.174 ….. Bill Buckner

0.174 ….. Jorge Posada

0.173 ….. Travis Fryman

0.173 ….. Robinson Cano

0.173 ….. Vinny Castilla

0.173 ….. Willie Montanez

0.173 ….. Roberto Alomar

0.173 ….. Darrell Porter

0.173 ….. Aubrey Huff

0.173 ….. Robin Yount

0.172 ….. Gary Carter

0.172 ….. Ron Cey

0.172 ….. Larry Parrish

0.172 ….. Willie Horton

0.172 ….. Ken Caminiti

0.172 ….. Ron Gant

0.172 ….. Eric Chavez

0.171 ….. Jeff Burroughs

0.171 ….. Derrek Lee

0.171 ….. Terry Pendleton

0.171 ….. Greg Vaughn

0.171 ….. Barry Larkin

0.171 ….. Lou Piniella

0.170 ….. Troy Glaus

0.170 ….. Todd Zeile

0.170 ….. Cal Ripken

0.169 ….. Tim Wallach

0.169 ….. Sal Bando

0.169 ….. Alfonso Soriano

0.169 ….. Jose Guillen

0.169 ….. Eric Karros

0.168 ….. Brian Downing

0.168 ….. Dave Kingman

0.168 ….. Kirk Gibson

0.168 ….. Bret Boone

0.168 ….. Wade Boggs

0.168 ….. Andre Thornton

0.167 ….. Jeromy Burnitz

0.167 ….. Dan Driessen

0.167 ….. Norm Cash

0.167 ….. Ryne Sandberg

0.167 ….. Carl Crawford

0.167 ….. Jermaine Dye

0.167 ….. Richie Hebner

0.167 ….. Darin Erstad

0.167 ….. Claudell Washington

0.167 ….. Willie McGee

0.166 ….. Rod Carew

0.166 ….. Adrian Beltre

0.166 ….. Don Baylor

0.165 ….. Doug DeCinces

0.165 ….. Phil Garner

0.165 ….. Tony Phillips

0.165 ….. Chris Chambliss

0.165 ….. Derek Jeter

0.165 ….. Lou Whitaker

0.165 ….. Gary Gaetti

0.164 ….. Shannon Stewart

0.164 ….. Tony Fernandez

0.164 ….. Gary Matthews

0.164 ….. Jose Reyes

0.164 ….. Carlton Fisk

0.164 ….. Vernon Wells

0.163 ….. Buddy Bell

0.163 ….. Reggie Sanders

0.163 ….. Dwight Evans

0.163 ….. George Scott

0.163 ….. Ivan Rodriguez

0.163 ….. Jorge Orta

0.162 ….. Johnny Damon

0.162 ….. Adam Dunn

0.162 ….. Lloyd Moseby

0.162 ….. Shawn Green

0.161 ….. Delino DeShields

0.161 ….. Jose Valentin

0.161 ….. Andruw Jones

0.160 ….. Ray Durham

0.160 ….. Jimmy Rollins

0.160 ….. Craig Biggio

0.159 ….. Brian Roberts

0.159 ….. Chuck Knoblauch

0.159 ….. Carney Lansford

0.159 ….. Garry Maddox

0.159 ….. Mark Loretta

0.158 ….. Orlando Cabrera

0.158 ….. Vada Pinson

0.158 ….. Graig Nettles

0.158 ….. Kenny Lofton

0.158 ….. Alex Rios

0.158 ….. Jay Bell

0.157 ….. Ken Griffey1

0.157 ….. Brady Anderson

0.157 ….. Rickey Henderson

0.157 ….. Mike Cameron

0.157 ….. Marquis Grissom

0.156 ….. Juan Samuel

0.156 ….. Curt Flood

0.156 ….. Randy Winn

0.156 ….. Devon White

0.156 ….. Jhonny Peralta

0.155 ….. Lance Parrish

0.155 ….. Jose Cardenal

0.155 ….. Damion Easley

0.155 ….. Johnny Callison

0.155 ….. Dave Concepcion

0.154 ….. Eric Young

0.154 ….. Brooks Robinson

0.154 ….. Rich Aurilia

0.154 ….. Raul Mondesi

0.154 ….. Garry Templeton

0.153 ….. Don Money

0.153 ….. A.J. Pierzynski

0.153 ….. Rafael Furcal

0.152 ….. Toby Harrah

0.152 ….. Chet Lemon

0.152 ….. Edgar Renteria

0.152 ….. Alan Trammell

0.152 ….. Rick Monday

0.152 ….. Tom Brunansky

0.151 ….. Jason Kendall

0.151 ….. Placido Polanco

0.151 ….. Mark Kotsay

0.150 ….. Roy White

0.150 ….. Dave Martinez

0.150 ….. Bob Boone

0.149 ….. Steve Finley

0.149 ….. Roy Smalley

0.149 ….. Jose Offerman

0.148 ….. Benito Santiago

0.148 ….. Dick McAuliffe

0.147 ….. Enos Cabell

0.147 ….. Bobby Grich

0.147 ….. Frank White

0.145 ….. Shawon Dunston

0.145 ….. Steve Sax

0.144 ….. Jim Fregosi

0.144 ….. Mark McLemore

0.144 ….. Alex Gonzalez

0.144 ….. Ozzie Guillen

0.144 ….. Willie Randolph

0.144 ….. Davey Lopes

0.143 ….. Ichiro Suzuki

0.143 ….. Cookie Rojas

0.143 ….. Jim Gantner

0.142 ….. Mark Grudzielanek

0.142 ….. Jim Gilliam

0.142 ….. Mike Bordick

0.141 ….. Ozzie Smith

0.141 ….. Juan Pierre

0.141 ….. Bill Freehan

0.141 ….. Chris Speier

0.139 ….. Brett Butler

0.138 ….. Leo Cardenas

0.138 ….. Tommy Harper

0.138 ….. Greg Gagne

0.137 ….. Jim Sundberg

0.137 ….. Omar Vizquel

0.137 ….. Tony Pena

0.136 ….. Willie Wilson

0.134 ….. Royce Clayton

0.133 ….. Brad Ausmus

0.132 ….. Manny Trillo

0.132 ….. Luis Aparicio

0.130 ….. Aurelio Rodriguez

0.129 ….. Bill Russell

0.129 ….. Bert Campaneris

0.129 ….. Alfredo Griffin

0.126 ….. Paul Blair

0.125 ….. Luis Castillo

0.118 ….. Ed Brinkman

0.1047 ….. Larry Bowa

0.1045 ….. Mark Belanger

Thank you, Richard. The list is a nice mix of expected results and surprises. Five of the six searchable members of Voomo’s list are in the bottom 25, which is expected, but I’d have expected the sixth to be Campaneris, rather than Concepcion — and that Campanaris that that low is a surprise.

In you earlier list, you calculated two ways, counting the batter himself as a ROB and not. Which method did you use for this one?

In my first sentence I mentioned that I did not count the batter as a base runner.

You did, indeed, Richard. Another point for my fifth grade teacher and her warnings to me about sloppy reading . . .

Interesting that the list doesn’t come to a guy who doesn’t “take a walk” until Juan Gonzalez (15th). I guess free swinging (or expanding the strike zone ?) doesn’t get the ducks off the pond

I imagine you can make a decent sized list of ‘one-tool’ players for all five tools (six, really, if you count batting eye as a tool like I usually do), except maybe throwing arm, since most of the guys famed for having great arms brought something else to the table (Joe Ferguson had a heck of an arm, good enough to get played in the OF sometimes, but the Dodgers wouldn’t have carried him if he couldn’t catch and didn’t have some good offensive years).

Of course, ‘one tool’ is an oversimplification. Max Bishop was a ‘one tool’ batting eye type of player, though he had some seasons where rField shows him as a very good defensive 2B. Ferris Fain might be thought of as a one tool guy, though he was passable as a defensive 1B and led the league in average twice.

But certainly, with the glove tool and hit for power tool, you can name dozens of guys that stuck around for years bringing little else of value. You also have a handful of speed merchants who got by without ever really parlaying that speed into great hitting or defensive numbers (Vince Coleman comes to mind).

Point taken, CC. I guess I was thinking of exceptional cases of important “disabilities” by outstanding stars (like Lombardi’s case) or outstanding disabilities by important players (like Belanger’s case). I wasn’t thinking of one-tool players so much as one-key-tool-completely-broken players.

Bishop and Fain (to pick on Connie Mack’s guys), really didn’t cost the A’s anything in their weak points. Bishop wasn’t a terrible hitter, even without the walks: just more or less what you’d expect from a good second baseman. And Fain wasn’t bad at anything: he just wasn’t all that good at anything, either, which surprises everyone who knows he won consecutive batting titles.

Maybe the best example would be Bill Bergen, who makes Belanger look like Ted Williams, but who had some amazing version of that thing that catchers sometimes have that led his team and his contemporaries to see him as a very good player. Year after year of .160-ish BAs, along with league leading <je ne sais quoi . . .

Ah, yes, that is a slightly different topic. I would imagine there still exist plenty of guys for each tool that would grade out as an F but still managed to be productive players. Some of them are less interesting than others, since many are seen as endemic to the position – a shortstop in the 1950’s who grades out as an F in power isn’t going to strike anybody as being exceptional, nor is a catcher who grades out as an F in speed.

Of course, there are always the absolute pinnacles. Lombardi may not statistically be the slowest player ever (I believe I once made a good argument for Johnny Estrada to take that distinction – in his career he had 129 doubles, 0 triples, 0 stolen bases, 0 SB attempts, and from an admittedly cursory game log search from a few years ago I never found an occasion where he was thrown out attempting to stretch a double into a triple – dude knew his limitations), but he is the Platonic ideal of a slow footed baseball player. Bergen is certainly the ne plus ultra of all glove/no hit players, holding pretty much every negative distinction for offensive futility possible. On the throwing arm side, you’ve got some pretty famous noodle arms like Johnny Damon, and guys who had the yips like Sax and Knoblauch. For iron gloves, you have the Dick Stuarts of the world.

This is completely unfounded, but I imagine on average the guys with ‘worst in one tool’ ratings with decently long careers actually provided a bit more value than guys who were slightly above average at everything. My rationale being that, managerial incompetence aside, a guy with one extremely glaring weakness tends to only stick around if his corresponding strengths are enough to substantially outweigh those weaknesses. They’re also easier to dump once their strengths disappear – if a guy who is average at everything starts to struggle a bit with his bat but not his glove, you might keep him around. If Rob Deer starts hitting only singles or Mark Belanger starts booting routine ground balls, you cut him.

Since 1901 for players with 3000+ PA, Fain’s .424 OBP puts him in 10th place (tied with Eddie Collins) and Bishop’s .423 OBP puts him in 12th place (tied with Shoeless Joe Jackson).

As far as one tool, did Dave Kingman do anything besides hit for power? Off the top of my head, I don’t remember him taking a walk (or even being pitched around), and I recall the Giants tried him at 3B but he was basically a corner OF , DH, and 1B who didn’t distinguish himself with the glove.

He may have been able to throw (I believe he pitched at USC) ? He didn’t run well either…..

Only in 1979, when he actually hit for a decent average and led the league in OPS. Joe Posnanski wrote an article about it about a decade ago for SI, basically saying that he felt Kingman could have been better but simply didn’t care enough. I usually think it’s unfair to apply that sort of armchair psychoanalysis to somebody from afar, but he made some seemingly convincing points. Basically, Kingman said before 1979 (just two years after he’d been released by four different teams in one season) that he was going to stay healthy, that he’d stop always swinging for the fences, he’d take the ball the other way, and so on. It may have seemed like bluster, but he actually did it – the first four months of the season, his batting line was .306/.378/.691. Sure, it’s not the best line ever, but for Kingman, a .300 average may as well have been .500, and this is a guy whose OBP through 1978 was .299. He cooled off a bit, but still had a tremendous season. He hit pretty well again in 1980, though I believe he got injured. After that, he turned into the Kingman of old – the remainder of his career was 3,175 PA’s of .226/.295/.442 hitting with 172 dingers.

Posnanski gave a few other situations where Kingman seemed to have a reason to step up – for example, Kingman was born to hit at Fenway, and he hit 13 HR’s in 18 games there with a slash line of .276/.345/.816. And in 64 PA’s where a player was intentionally walked in front of him, he hit .407 with 11 homers.

CC,

Kingman actually had 47 OF assists in 648 OF games so, basically, about 12 assists per 162 G. By the same token, maybe he didn’t throw well at all and this was just a case of gunning down overly aggressive base runners taking liberties with a sub-par arm?

I have a fairly distinct memory of Kingman worrying people that, with the DH, he might stay around long enough to hit 500 HR. At that time, 500 was still a mountain, and there was speculation about a possible HOF vote for someone who clearly wasn’t HOF material, but…if he hit 500, could he be kept out. Kingman had hit 35, 30 and 35 HR in what would be his final three seasons.

Paul, Kingman actually had a good arm. He started out as a pitcher, and in the one game he pitched in the Majors, although he was really wild, he did strike out four in four innings. His good arm explains why the Giants originally put him a third, even though he was a poor ball handler. If the errors had gone away, he’d probably have been fine in the field, since his range factor was above league average and he did have a pitcher’s arm.

I remember expecting Kingman to be another Frank Howard. He hit more HRs than Hondo, but had only one big year and never seemed to figure out that he could contribute with walks, as Howard did. It wasn’t really the number of HRs that made Kingman’s reputation, I think: it was the length of the home runs, and I think that has a lot to do with his hitting defects. I suspect he went to the plate hoping to make the crowd gasp, rather than hoping to contribute to wins. (But, just for reference, although Kingman is in the bottom half of players on Richard’s %RDI list, above, he’s not anywhere near the bottom.)

epm, that was basically Posnanski’s conjecture. He figured Kingman didn’t really enjoy playing baseball – he enjoyed hitting mammoth home runs. All the in-between parts – especially dealing with the media – were just tedious interims between the next long fly.

Too bad the Home Run Derby didn’t start till Kingman was too near done to be selected. Seems it’s the game he was really born to play, rather than baseball.

Yep, 35 HR in his final season, with a -1.0 WAR.

Poorest WAR in a 35 HR season:

-1.0 … Kingman

-0.8 … Tony Armas

-0.4 … Adam Dunn

0.1 … Kingman

Dunn did that in one of his finest offensive seasons. He was (dis)credited with an extraordinary -43 Rfield, which is the worst number ever recorded for that stat.

I expect that within a few days, Doug will lead HHS to new topics with a new post and we won’t likely return to discussion of 19th century baseball for a long time (probably until the next CoG election raises the issue of the candidacies of Bill Dahlen and Bobby Wallace again). There were a number of matters that I couldn’t fit into my already-too-long posts and was hoping to smuggle into discussion comments. It looks as though the opportunity for smuggling is ending, but there’s one matter that has a particular appeal to me that I’d simply like to tack on now, when there is at least some pretext of relevance. It has to do with an ongoing dynamics of past experience influencing current behavior that must pertain to baseball today as much as it did in the 1890s.

Somewhere in my posts, I mentioned that the early NL did not create much precedent for the idea of dramatic upward mobility: teams emerging from obscurity to become league powers, and this raises a question about Ned Hanlon and the Orioles: Whatever gave Hanlon the idea he could transform a bottom-dweller into a champion? Other managers in Hanlon’s position, like Gus Schmelz with the weak Washington team, took their task to be getting the best they could out of their players and improving the team record, but Hanlon’s approach was to accrue enough executive leverage to make a new team and win it all. I can’t prove it, but I think that it’s overwhelmingly likely that the reason Hanlon had this approach was because he had in mind the one prior example of this actually happening in the NL: the rise of the Detroit Wolverines in the 1880s.

The short-lived Wolverines were a mediocre team from their creation in 1881 through 1885. In 1884 and 1885 they had W-L percentages of .250 and .380, and seemed unlikely to survive. They were purchased then by a rich and ambitious new owner, Frederick Stearns, who transformed them by buying up the rights to the four best players on another dying team: the Buffalo Bisons. The Bisons were an awful team (total WAR in 1885: 4.6) with a group of fine position players, known as their “Big Four” (total WAR in 1885: 12.8). With that new infusion of players, Detroit became a .707 club in 1886 and won the pennant in 1887. The league’s other owners, upset with Stearns’ methods and results, changed the game-revenue splitting formula in a way that would drive the Wolverines out (Detroit was a small city then, and needed a high-percent visitors’ share formula). The team folded after the 1888 season.

The manager of the Wolverines was, like many 1880s managers, an administrative type rather than a baseball man, and he left game decisions to the player-captain of the team, which was then a common practice. That captain was Ned Hanlon. Apart from Hanlon benefiting from the “inside baseball” pioneers, Schmelz and Selee, I think what distinguished him, in part, was his personal experience watching Stearns transform Detroit and break the virtual power monopoly that Chicago and Boston had generally sustained in the NL. I think it’s no accident that Hanlon’s final big trade prior to the Orioles first championship brought Dan Brouthers, the best of the old Buffalo “Big Four,” to Baltimore, and that after the Orioles had become winners, he sent Brouthers packing and anointed his own leading players (McGraw, Jennings, Keeler, and Joe Kelley) as the Orioles’ “Big Four.”

What I like about this, even though it’s a speculative idea (I don’t know of any statement by Hanlon confirming that Stearns and the Wolverines were an inspiration to him), is that it illustrates the way multiple dimensions of experience and precedent may combine to create something that is entirely new, but that nevertheless grows out of the past. When we look at players, managers, and executives in baseball today, I assume the same dynamic is always at work. It’s not just a matter of talent, personal/personnel skills, knowledge of the latest analytic tools, and money setting the directions of players and teams: the models of past formulas for success that individuals have observed or learned about, which they select and rely on in approaching their tasks, also shape the way seasons unfold.

EPM, I think you have surpassed yourself. How about organizing this and more and looking to get it published?

SABR publishes a semi-annual Baseball Research Journal, epm could try contacting them. I’ve already mentioned that to Doug. Also I mentioned to him that his (Doug’s) articles are also publishing worthy. It’s a shame that so few people are reading those articles.

As a SABR member that receives the BRJ, I can confirm that the output at HHS is superior to 99% of the output from those journals (which is no insult to those authors – the stuff here is just that good), and I’d absolutely encourage both Doug and epm to publish.

Many thanks to Mike and others for the kind words. I agree that many of Doug’s analytic posts would be well suited for the BRJ. As for my series, I don’t see it as real research — my resource base was very narrow, and I don’t know enough to know what I probably don’t know. My goal in writing was advocacy: I’m hoping HHS readers, whether they’ve commented on these posts or not, will be more open to some process that allows our CoG voting to add the 19th century, maybe as an added “wing.”

The Circle has become the site’s energy core (salute to birtelcom!) and the vote discussions are great. All of us can see that HHS has been losing members and slowing down over the past couple of years. I’d like to think a well-done process for posting profiles of leading 19th century players, perhaps by position and perhaps sorted by pre- and post-1893 periods, and then having voting discussions would be fun and draw back some of our absent members (where have Doom, nsb, the Tunas, and many other good regulars been?).

My posts were intended to add to Doug’s in building some groundwork, and I didn’t really expect too many comments on them, since they were longwinded and designed to argue my opinion more than to invite others’ (kind of like me in real life — except that I did hope they’d be entertaining). But I do think baseball history is interesting in every period, and that if we know more about pre-1901 baseball, we’ll want to talk about it as we do the later periods, using stats to explore issues, making arguments about which players are best, finding anomalies and surprises (as Voomo, for example, does so well), and so forth. . . . That’s really what I’m aiming for.

Speaking for myself, I can confidently say that I have learned as much or more about the 19th century game from epm’s posts and comments than from any other source. Thanks so much, epm.

I’m traveling on holiday right now, but will have some new posts in another week.

Many thanks, Doug. Enjoy your travels!

Since we may have reached the end of this string, and new posts will await Doug’s return from vacation, I’m going to append a clarification to a garbled passage in the first of the three posts on the Orioles. (Apologies for being so wonky!)

The passage in question comments on a table showing the 1892 Orioles’ record in the context of the stats of the 12-team NL. That awful team had a DER that, compared to league average, was -7.0%, and an ERA+ that was at -19.0%. Having converted all the stats in these tables from absolute values to percent-above/below format, I noticed that this made it appear that the Orioles were worse in pitching quality than in fielding quality, relative to other teams. But the fact is that ERA+ simply varies more in percentage terms than DER does, because such a large proportion of balls in play are turned into outs by any professional team.

I tried to convey this about DER and ERA+ and completely botched it:

What I meant to say was that even though it might seem that being 19% below league average in ERA+ was worse than being 7.0% below in DER, that’s not the case, because the stats vary in different ranges. It is DER, not ERA+, that is relatively inelastic (tends to vary little from average). While you can find plenty of teams worse than 19% below league average when it comes to ERA+, you need to look at the worst team in history (Cleveland in ’99) to surpass the Orioles’ negative 1892 DER rate of -7.0%.