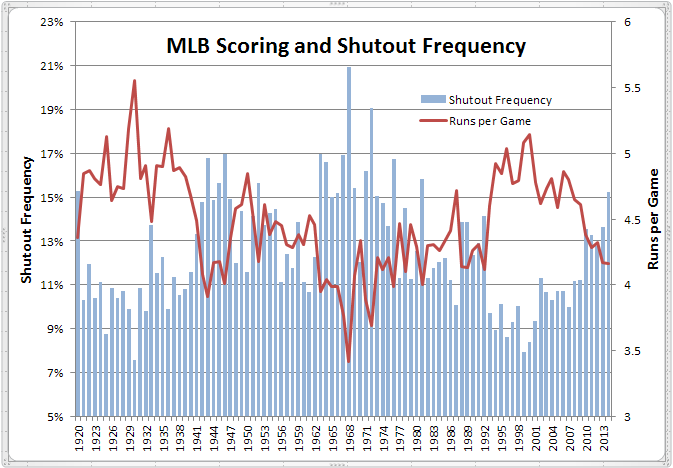

Thus far in 2014, the recent trend towards lower scoring continues. That trend is now more than 15 years in the making and has resulted in another, that of a higher incidence of shutouts (at least those of the team variety). So far in 2014, more than 15% of games have resulted in a goose egg for the losers, a proportion not seen since 1981, and not seen in a full-length season since 1976.

After the jump, more on declining offense and why it’s been happening.

To illustrate my point about shutouts and run scoring, here’s a chart of the live-ball era showing frequency of shutouts and average runs per team game.

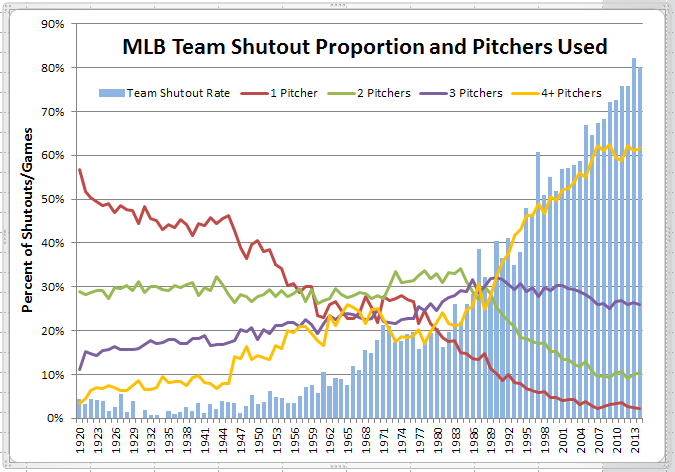

While both measures are now in the range experienced from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. how that has resulted in today’s game is markedly different from the past. That fact is illustrated in the chart below.

The blue bars represent “team shutouts” (those involving two or more pitchers) as a proportion of all shutouts. Almost negligible at the start of the live ball era, their incidence rose to about 20% by the early 1970s, doubling to 40% by the early 1990s, and doubling again to 80% today. That result is a byproduct of the other trends on the chart, showing the proportion of team games involving one, two, three and more pitchers, with reductions in the former two categories producing a huge increase in the latter category.

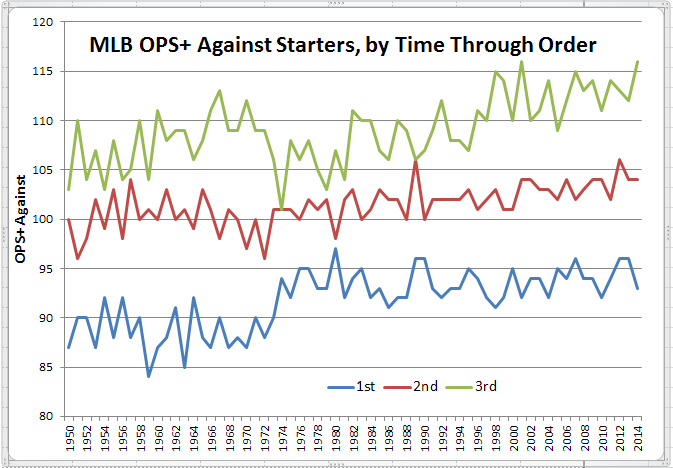

But, why has pitcher usage changed so dramatically? An explanation is indicated by the chart below, showing OPS+ against starting pitchers in the first, second and third times through the batting order.

These data are mostly complete for the period shown, since 1950. The effect of the DH is easily discerned, with an increase in OPS+ for the first and second times and a reduction (initially) for the third time, the latter an indication that the immediate response to the DH was for AL teams to go longer (but, only a bit longer) with their starters who, on the whole, did better than the relievers who had formerly been used in that spot. This effect was probably most pronounced in the circumstance of effective starters getting inadequate run support and thus having to be reluctantly removed for pinch-hitters. With the DH in effect, those starters remained in the game and continued to pitch effectively.

Also notable is the improvement in OPS+ over time, for each of the three times through the order. I’ll explain later why that has more to do with relief pitching than starting pitching. For now, the more important trend is that batters become more effective against starting pitchers each time through the order. So, should we expect that trend to continue for the fourth time through the order?

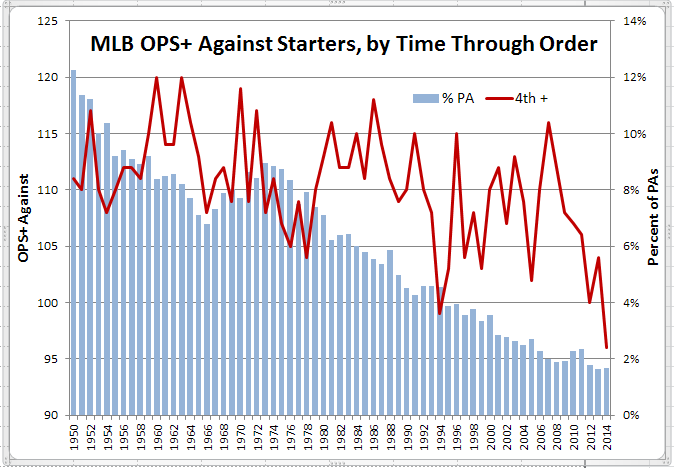

It did indeed through the early 1970s, with OPS+ scores (brown line) of 110 and higher, compared to a 105 to 110 range for the third time. But, those OPS+ scores then start to decline. But, only because of selection bias as indicated by the blue bars showing a corresponding decline in the proportion of PAs against starters in their fourth time through the order. Thus, only starters who were truly on their game were sticking around to have a fourth go at the opposition, while the rest were giving way to relievers. How did those relievers fare?

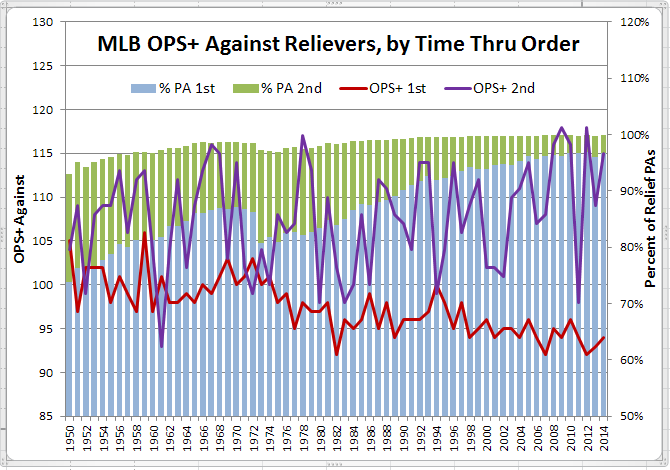

Prior to the DH rule, not so well with OPS+ scores inferior to those of starters. But since then, those OPS+ against scores have steadily improved, with a corresponding increase in the proportion of innings pitched. This result also explains the improved results (as measured by OPS+) for batters against starters. If relievers are doing better measured by OPS+ against, then starters must therefore be doing worse.

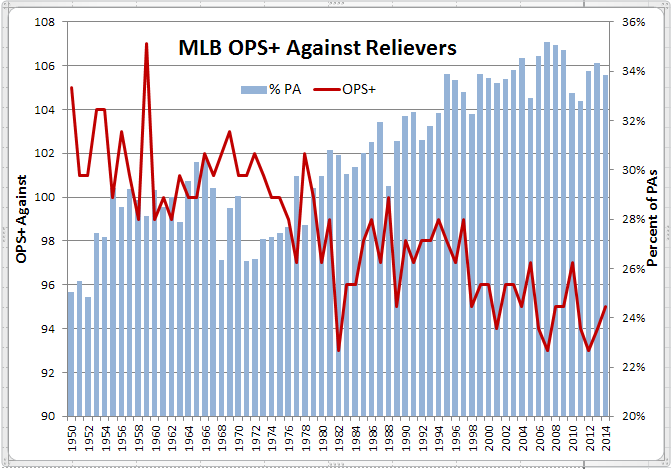

But, note that the proportion of PA by relievers has been basically level for the past 20 years, even as their effectiveness has continued to improve. The cause of that effect is suggested by the chart below, breaking down reliever usage and performance by times through the batting order.

Today it’s only in long relief that relievers stay in a game for a full tour of the batting order, much less more than one. But, it hasn’t always been thus. Even as late as the mid-1980s, 15% or more of relief PAs were against pitchers being seen for a second time. As with starters, relievers’ effectiveness was notably reduced their second time through the order.

But, note the last 15 seasons and the consistent 96 OPS+ or worse by hitters against relievers in their first (and, usually, only) look at them. Much as we might decry specialization of pitching roles and the resulting push-button managing of pitching staffs, bottom line is you can’t argue with success. Of course, it hasn’t all been the pitchers. Batters are doing their share by taking healthy cuts in *all* of their PAs, and thereby keeping an ever-increasing number of balls “out of play”. And, with ever-expanding pitching staffs come ever-shrinking benches, giving the defense the upper hand in late-inning matchups.

So, where are we headed from here? Let’s look again at my first chart.

As I noted earlier, runs per game and shutout frequency are both about where they were for a 20-year period from the early 1970s to early 1990s. Then came the offensive explosion of the 1990s and 2000s triggered, in part (perhaps a large part?), by PEDs. Now that PEDs appear to be mostly eliminated, is it just a coincidence that we’re back in the range of the relative offensive/defensive “equilibrium” of the pre-PEDs era? If not, is it reasonable to surmise that, absent PEDs, that equilibrium might have persisted over the past 20 years? Questions to ponder.

Thought to ponder. Although OPS+ against starters is lowest the first time around, a PI run from 1960-2013 shows that there have been more runs scored in the first inning than in any other.

Good point, Richard.

Evidently, always having your best hitters batting in the first inning compensates (at least for that inning) for facing the starter for the first time.

It’s possible that a prevalence of SB in the first inning is a cause of many runs being scored with a low OPS+, since SB do not contribute to OPS+. The PI run covers the years 1960 to 2014, and not all the years at that. The PI run shows 23501 SB, or 18,5% of the total of all SB, occurring in the first inning. That’s 7000+ more SB than in the third inning, which has the second most AB.

Just noted a typo. The last entry should be SB, not AB.

Doug, this is an excellent, comprehensive look at these trends.

Given overwhelming evidence that short outings are most effective, the questions I’d most like to discuss are:

(1) How will usage strategies evolve from here; and

(2) Is it time to consider rules limiting pitcher moves in a game?

As to (1), I keep expecting some team to try a 4-man rotation, but with even tighter pitch limits. The 5th starter’s a weak link on almost every team, yet virtually everyone religiously sticks to a 5-man rotation, not even using off days to skip #5. Top starters now get just 33-34 starts per year; the past 3 seasons were the first full ones ever with no one at 35+ starts.

Even the best starters tend to decline in the 3rd and 4th times through the order. Why not try shorter starts, but more of them? A 4-man rotation making 40 starts each, but with a target of 6 IP, would not have to log more innings than a 5-man rotation, but they might well be more effective innings.

As for (2), I strongly believe there should be some limit imposed on the number of pitching changes. I recall a recent game in which one fresh reliever started an inning, followed by three more changes that same inning — four pitchers, to face five batters, with no runs scored. Who wants to *watch* a game like that?

I would gladly adopt the limit on mid-inning changes that Bill James proposed in The Historical Abstract: Each team gets one free mid-inning change, but no more until a run has scored while the current pitcher was in.

If a team wants to use nine pitchers for an inning apiece, that’s fine with me — as long as I don’t have to watch them warm up, while everyone else stands around waiting.

The unregulated pitching changes also impact offensive strategy. In the early years of the rise of relief pitching, pinch-hitting increased, as offensive managers sought a platoon edge. If the other side countered, well, offense gets the last move, and with deeper benches, skippers weren’t afraid to hit for the pinch-hitter.

But as benches have shrunk due to extra relievers, managers are more reluctant to make either move. Since 1990, the number of pinch-hitters used has shrunk by 15%, and the number of double-PH moves has dropped by half. Sometimes they just think, why bother putting in my LHB now, since they’ll just bring in a southpaw, and I don’t want to burn half my bench in one move?

How about limiting the number of pitchers on a roster as another move?

I would vote for that. Twelve should be more than enough.

And, I’d bump the roster to 26 spots (the owners can afford one more paycheck).

Re: a roster limit on pitchers — No one is officially a “pitcher” except when they pitch in a game. And “nonpitchers” do pitch once in a while. To implement a roster limit, wouldn’t you have to create official designations?

Rather than force a team to stick with the same pitcher while he (for example) loads the bases, perhaps the answer is to limit the warmup pitches. The normal complement for the first in-inning change, 4 for the next, 2 for the next, and none after that.

Just thinking about the rule of no further changes until a run scores, would that lead to some weird things happening if the manager really, really wanted to change pitchers? Like IWs (or even intentional balks) to force in a run (but only one) so the next pitcher could come in. Or a sudden upsurge in “tweaks” and other feigned maladies, as a way to force a pitching change without giving up a run. Absurd, you say? Possibly. But, that’s the problem with arbitrary rules based on events outside of a team’s control – you never know where things might lead in efforts to get around those restrictions.

Doug, I don’t think it would be hard to write my rule to discourage feigned injuries. Say … A pitcher removed mid-inning by an injury exception can’t play in the next two games.

And I’m not sure what you mean by “arbitrary.” It targets a particular problem — at least, some think it’s a problem — by means of a restriction that is hardly draconian.

But I would be open to modifications. “Two men reaching base” could be added to “a run scoring” as the trigger allowing a mid-inning change.

The rulebook is chock full of restrictions that were drawn up after someone started exploiting a gap. When Earl Weaver started submitting lineups with a pitcher as DH, then choosing his actual DH based on the situation when that spot first came to bat, MLB closed the loophole: Now, the starting DH must bat at least once, unless there’s a pitching change.

If a limit on mid-inning pitching changes was imposed, I’m sure managers would find some ways to game the system, sometimes. But I’m also sure that they would generally adapt and accept the rule. I think some would welcome it. Not every manager is a Tony LaRussa who *wants* to micromanage the late innings. Some, I think, would be happy to have that moment-to-moment decision pressure relieved.

Limiting warmup pitches may be worth considering, as an alternative to limiting changes. But the warmups themselves are less than half the dead time involved in a pitching change. And I worry about what will happen the first time a no-warmups pitcher gets injured in some way connected to pitching from an unfamiliar mound.

I have heard the suggestion that if a reliever faces only one batter, the second reliever must begin pitching immediately without warmups.

Doug, this was fantastic.

I think you pretty much nailed the TTOP (times thru the order penalty).

________

I am totally on board with the suggestions to curb pitching changes/# of pitchers in the comments above. Baseball is becoming increasingly harder to watch, even for a lot of seasoned fans.

It’s a hidden crisis, masked by turnstiles still clicking at an acceptable enough pace for those running baseball to remain struthious about an obviously-looming problem. What happens to attendance ten or twenty years from now when a generation of fathers DON’T take their families to a baseball game because they didn’t grow up watching the sport?

For Frith’s sake, Bud, find us a new commissioner who is forward-thinking enough to address the downward-spiraling watchability of the game we love.

This is a great study with very readable charts. Thanks. I agree with the suggestions about limiting pitching changes during innings when a run hasn’t been scored.

The rosters should be increased to 27 players. If you go back rosters weren’t always set at 25. In the early part of the 20th century rosters were much smaller. The game has evolved and a 25-man roster does not allow for enough bench or platoon players. I’d suggest limiting teams to 13 pitchers as well.

Re: expanding rosters to 27 — Given two extra roster spots, I would bet that most teams would add at least one reliever. Some would add two relievers. Expanded rosters might just make the problem worse.

As long as we’re fantasizing about rule changes that won’t happen – why not limit teams to one mid- inning change for each nine inning game , with some adjustment for extra frames? If a pitcher was injured after his team had used up the change — he could be replaced by another player who was on the field at the time, say ,the 2B , who could be replaced by effectively a “pinch fielder” , a real pitcher would warm up to start the next inning, and the fielder could return to his position. – this would happen about twice a season , and would be no more comical than watching Bartolo Colon swing .

Re: JA @10

Maybe arbitrary is the wrong word. I just meant that having to wait for the opposition to score (something a team can’t control) before making a move seemed a little strange. At least a rule like two mound visits is something a team can control. Maybe a minimum two or three BF instead of one would help. Would make managers think twice about whether thay really need to make that change.

How about a simple rule prohibiting the use of any pitcher two games in a row (except during extra-innings or during the game after an extra-inning game)? Would that likely move pitcher usage patterns back a few decades? Could create lots of fun head-scratching strategy decisions for managers.

Pingback: High Heat Stats » Scoring is down (again). Should something be done?