This post is for voting and discussion in the 132nd round of balloting for the Circle of Greats (COG). This is the last of four rounds of balloting adding to the list of candidates eligible to receive your votes those players born in 1974. Rules and lists are after the jump.

The new group of 1974-born players, in order to join the eligible list, must, as usual, have played at least 10 seasons in the major leagues or generated at least 20 Wins Above Replacement (“WAR”, as calculated by baseball-reference.com, and for this purpose meaning 20 total WAR for everyday players and 20 pitching WAR for pitchers). This fourth group of 1974-born candidates, comprising those with P-Z surnames, joins the eligible holdovers from previous rounds to comprise the full list of players eligible to appear on your ballots.

In addition to voting for COG election among players on the main ballot, there will be also be voting for elevation to the main ballot among players on the secondary ballot. For the main ballot election, voters must select three and only three eligible players, with the one player appearing on the most ballots cast in the round inducted into the Circle of Greats. For the secondary ballot election, voters may select up to three eligible players, with the one player appearing on the most ballots cast elevated to the main ballot for the next COG election round. In the case of ties, a runoff election round will be held for COG election, while a tie-breaking process will be followed to determine the secondary ballot winner.

Players who fail to win either ballot but appear on half or more of the ballots that are cast win four added future rounds of ballot eligibility. Players who appear on 25% or more of the ballots cast, but less than 50%, earn two added future rounds of ballot eligibility. One additional round of eligibility is earned by any player who appears on at least 10% of the ballots cast or, for the main ballot only, any player finishing in the top 9 (including ties) in ballot appearances. Holdover candidates on the main ballot who exhaust their eligibility will drop to the secondary ballot for the next COG election round, as will first time main ballot candidates who attract one or more votes but do not earn additional main ballot eligibility. Secondary ballot candidates who exhaust their eligibility will drop from that ballot, but will become eligible for possible reinstatement in a future Redemption round election.

All voting for this round closes at 11:59 PM EDT Sunday, March 17th, while changes to previously cast ballots are allowed until 11:59 PM EDT Friday, March 15th.

If you’d like to follow the vote tally, and/or check to make sure I’ve recorded your vote correctly, you can see my ballot-counting spreadsheet for this round here: COG 1974 Part 4 Vote Tally. I’ll be updating the spreadsheet periodically with the latest votes. Initially, there is a row in the spreadsheet for every voter who has cast a ballot in any of the past rounds, but new voters are entirely welcome — new voters will be added to the spreadsheet as their ballots are submitted. Also initially, there is a column for each of the holdover candidates; additional player columns from the new born-in-1974 group will be added to the spreadsheet as votes are cast for them.

Choose your three players from the lists below of eligible players. The current holdovers are listed in order of the number of future rounds (including this one) through which they are assured eligibility, and alphabetically when the future eligibility number is the same. The 1974 birth-year players are listed below in order of the number of seasons each played in the majors, and alphabetically among players with the same number of seasons played.

Holdovers:

| MAIN BALLOT | ELIGIBILITY | SECONDARY BALLOT | ELIGIBILITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luis Tiant | 8 rounds | Willie Randolph | 10 rounds |

| Dick Allen | 7 rounds | Rick Reuschel | 9 rounds |

| Manny Ramirez | 7 rounds | Todd Helton | 8 rounds |

| Bill Dahlen | 5 rounds | Bobby Abreu | 2 rounds |

| Graig Nettles | 3 rounds | Stan Coveleski | 2 rounds |

| Bobby Wallace | 3 rounds | Monte Irvin | 2 rounds |

| Ted Lyons | 2 rounds | Minnie Minoso | 2 rounds |

| Don Sutton | 2 rounds | Andy Pettitte | 2 rounds |

| Richie Ashburn | this round ONLY | Ken Boyer | this round ONLY |

| Andre Dawson | this round ONLY | Hideki Matsui | this round ONLY |

| Dennis Eckersley | this round ONLY | Bengie Molina | this round ONLY |

| Ted Simmons | this round ONLY | Reggie Smith | this round ONLY |

Everyday Players (born in 1974, ten or more seasons played in the major leagues or at least 20 WAR, P-Z surname):

Miguel Tejada

Shannon Stewart

Randy Winn

Richie Sexson

Jose Vidro

Preston Wilson

Pitchers (born in 1974, ten or more seasons played in the major leagues or at least 20 WAR, P-Z surname):

Jamey Wright

Jarrod Washburn

Glendon Rusch

Ugueth Urbina

Luis Vizcaino

Mark Redman

As is our custom with first time candidates, here is a factoid and related quiz question on each of the new players on the ballot.

- Jamey Wright’s career spanned 19 years, but he played in the post-season in just one of those seasons. Which contemporary of Wright’s had a longer pitching career and never played in the post-season?

- Miguel Tejada played 1152 consecutive games from 2000 to 2007, a span that included six seasons of 30 doubles, 20 HR and 100 RBI, the most for any shortstop. Who was the first shortstop to record such a season? (Joe Cronin, 1940)

- Shannon Stewart is the only Blue Jay to record consecutive seasons (2000-01) batting .300 with 20 stolen bases and 60 extra-base hits. Who is the only player to match that feat for Toronto’s expansion cousins in Seattle? (Alex Rodriguez, 1997-98)

- Randy Winn played 400 games for the Rays, Mariners and Giants. Which other player played 400 games for two of those franchises? (Omar Vizquel)

- Jarrod Washburn posted a .568 W-L% thru age 30 but only .381 after, despite maintaining a respectable 100 ERA+ in the later period. Who is the only expansion era pitcher to experience a larger such W-L% drop among those, like Washburn, with 1000 IP thru age 30 and 600 IP after? (Roy Oswalt)

- Jose Vidro is the Expos/Nats franchise leader in games played at 2B. Which one-time Expos second baseman recorded the most 2B games for the expansion Senators franchise before it relocated to Texas? (Bernie Allen)

- Richie Sexson played 1B for every inning of every game for the 2003 Brewers. Before Sexson, which first baseman was the last to do this for his team? (Mickey Vernon, 1953)

- Glendon Rusch’s 5.04 ERA is the fourth highest career mark of any pitcher with 200 starts. Among such pitchers playing their entire careers in the 20th century, who had the highest career ERA? (Herm Wehmeier)

- Luis Vizcaino is one of 22 retired pitchers with fewer than 10 saves in a career including 500 relief appearances. Who is the only pitcher in that group to finish fewer than 100 games in his career? (Ray King)

- Ugueth Urbina is the only major leaguer whose first and last names both begin with the letter U. What is the only major league battery with both players having a U surname? (Cecil Upshaw/Bob Uecker, 1967 Braves)

- Mark Redman recorded at least 29 starts for five consecutive seasons (2002-06), each with a different team. For his career, Redman toiled for eight franchises, the most by a pitcher with 200 starts in a career of ten or fewer seasons. Which pitcher with 300 starts has played for the most franchises? (Edwin Jackson)

- Preston Wilson‘s 2000 season featured the rare trifecta of 30 doubles, 30 HR and 30 stolen bases. Which player did the same and, like Wilson, led his league in strikeouts? (Bobby Bonds, 1973)

I’ll take the easiest one off the board first:

3. Alex Rodriguez, 1997-98

Q 10, Cecil Upshaw and Bob Uecker?

That’s it, on the 1967 Braves.

For Question 4, Vizquel definitely played 400 for both the Mariners and Giants.

Vote:

Richie Ashburn

Dennis Eckersley

Ted Lyons

Bobby Abreu

Willie Randolph

Rick Reuschel

The obvious guess for Question 12 is Bobby Bonds, so why not. I’ll guess Bobby Bonds.

Bonds leads everyone with 9 seasons of 20 HR + 30 SB. His son is second with 7 seasons. Nobody else has more than 4.

Question #7: I’l try Mickey Vernon in 1953.

Correct. Vernon also did it in 1942 and 1947.

In all, there were 34 such pre-expansion seasons by first basemen, but Sexson is the only one to do it in the expansion era.

Here’s the entire list.

1902 ….. Americans ………… Candy LaChance

1903 ….. Americans ………… Candy LaChance

1904 ….. Americans ………… Candy LaChance

1906 ….. Pirates ………… Joe Nealon

1907 ….. White Sox ………… Jiggs Donahue

1907 ….. Browns ………… Tom Jones

1911 ….. Cardinals ………… Ed Konetchy

1912 ….. Athletics ………… Stuffy McInnis

1917 ….. Yankees ………… Wally Pipp

1919 ….. Reds ………… Jake Daubert

1920 ….. Giants ………… High Pockets Kelly

1921 ….. White Sox ………… Earl Sheely

1925 ….. Cardinals ………… Jim Bottomley

1926 ….. Red Sox ………… Phil Todt

1928 ….. Robins ………… Del Bissonette

1929 ….. Braves ………… George Sisler

1932 ….. Pirates ………… Gus Suhr

1933 ….. Pirates ………… Gus Suhr

1934 ….. Indians ………… Hal Trosky

1934 ….. Browns ………… Jack Burns

1934 ….. Cardinals ………… Ripper Collins

1935 ….. Tigers ………… Hank Greenberg

1935 ….. Phillies ………… Dolph Camilli

1936 ….. Dodgers ………… Buddy Hassett

1938 ….. Reds ………… Frank McCormick

1940 ….. White Sox ………… Joe Kuhel

1940 ….. Tigers ………… Rudy York

1941 ….. Tigers ………… Rudy York

1942 ….. Senators ………… Mickey Vernon

1944 ….. Yankees ………… Nick Etten

1947 ….. Senators ………… Mickey Vernon

1948 ….. White Sox ………… Tony Lupien

1951 ….. Dodgers ………… Gil Hodges

1953 ….. Senators ………… Mickey Vernon

2003 Brewers ………… Richie Sexson

Ironic that Wally Pipp did it, but not his ironman successor Lou Gehrig.

I was thinking that Prince Fielder had done this as well. In 2009, he played 1431 out of 1435 defensive innings at first. Close, but no cigar. Casey McGehee had the other 4 innings.

I should probably be jumping for joy or something… but my main problem right now is that, for the first time in like 130 rounds, my ballot doesn’t have one spot already filled. Don’t get me wrong – I’m pretty ecstatic about the election of Brown, and I hate to re-litigate… but I’m sincerely interested in people’s arguments. Who is the BEST candidate on the ballot right now? I promise to read, as non-prejudicially as possible, any replies below this post, because after, like FIVE years of advocacy, my guy got in, and my ballot is open. I have inklings, but I’d like to hear from the community. And yes, I know we’ve done this a thousand times, but what’s one more? I know that, over the years, I’ve been persuaded to become a “yes” on Graig Nettles, Wes Ferrell, Satchel Paige, and perhaps others, though it’s hard to remember at this point. I’d really appreciate the help and guidance. Thanks, everyone!

Congratulations on your fierce advocacy. My problem with this group is identical to my problem with the last group–a lack of excitement with the choices. No new blood.

2. Glenn Wright ?

Q. 2: It looks like it’s Joe Cronin in 1940. Glenn Wright came close in 1930 with 28 2B, 22 HR and 126 RBI. Also Arky Vaughan in 1935 with 34 2B, 19 HR and 99 RBI.

Thanks Richard…… top of my head guess. Going backward, I thought “Vern Stephens”, “nah” then Cronin, remembered Vaughn never hit 20 homers and guessed Wright since one of those years with the Pirates or Dodgers had to be it…..and that would be incorrect 🙁

Dawson

Nettles

Eckersley

If Simmons drops off I don’t think we’ll forget about him and I’m starting to want Munson more.

Irvin

Randolph

Pettitte

Just some thoughts on some of the newcomers:

Jamey Wright: an ever-present reminder of the teams I grew up rooting for that routinely lost 100 games. Ah, late-90s and early-aughts Brewers; I don’t miss you at all.

Miguel Tejada: Tejada averaged 158 games played from 1999-2010, and that’s in spite of missing 29 games in ONE season. He sure was good at staying in the lineup and hitting baseballs very hard. He was less good at walking, avoiding double plays, and playing shortstop. Back when Melvin Mora was batting .340 and winning a batting title, having those two as the left side of the infield was pretty darn good for the O’s. Brian Roberts and Rafael Palmeiro actually made for just a plain good infield. Of course, the rest of the team was terrible, so they never had a winning record in Tejada’s four years. His traditional and sabermetric stats are uniformly too low for the COG and even the HOF, but it was a great career (chemically-aided though it surely was).

Shannon Stewart: My wife is a huge Twins fan. Her most hardcore fandom was from 2002-2004. So in our house, Shannon Stewart was a Twin, not a Blue Jay. Anyway, there’s one plan to get the Twins over that Yankees hump that never quite panned out… much like literally every other such plan.

Ugueth Urbina – What a great name. He saved two and blew one for the ’03 Marlins in the Series.

Preston Wilson – Now here’s one of those guys with a lot of value in fantasy leagues, but less value for MLB teams. He’s very Joe Carter that way. 60+ XBH three times, 50+ a couple more (80 one year – of course, that was Colorado in 2003, but still). Overall, 40% of his hits went for extra bases. He won an RBI title. League-average or better batting averages (in his prime anyway; roughly 1999-2003). A guy you’d want in fantasy baseball, particularly with CF eligibility every year. Of course, he was an atrocious CF and was so bad at taking a walk that, even in Colorado, with a batting average +.020 better than the league, he managed a barely-league-average OBP. Thus: 6.4 WAR in over 1100 career games. Sure, there may be players with 1000+ games played, less career WAR, and/or more than his 189 career HR, but that 29.5:1 ratio of HR to WAR is bad (seriously, if anyone with a PI subscription wants to look it up, I’d love to know how many have actually done worse). For comparison’s sake, it’s 20.2:1 for Joe Carter, a similar player with a better career; 25.5:1 for Dave Kingman, 26.6:1 for Adam Dunn, 16.7:1 for Rob Deer. The only player worse I find was the still-active(!!!) Mark Reynolds, at 34.6:1.

Doom,

” “Back when Melvin Mora was batting .340 and winning a batting title, having those two as the left side of the infield was pretty darn good for the O’s. Brian Roberts and Rafael Palmeiro actually made for just a plain good infield. Of course, the rest of the team was terrible, so they never had a winning record in Tejada’s four years”

WOULD HAVE THAT ENTIRE INFIELD BENEFITED FROM THE ADVANCEMENT IN PERFORMANCE ENHANCING DRUGS?

To answer my own question, Roberts, Palmeiro tested positive, I believe Tejada dis as well….. and did not Mora have a “late peak” or “find himself” relatively late? Small sample size here but, I guess Canseco and Caminiti weren’t kidding with those estimates between “50%” and “80%”.

Too bad they weren’t sharing with the outfield, then, isn’t it?

My other snark-loaded option was this one: Hey, it’s almost as if it was a problem MLB-wide, and not just isolated to a few people, isn’t it?

“” it’s almost as if it was a problem MLB-wide, and not just isolated to a few people, isn’t it? “”

Yes, but here we only concern ourselves with the cheaters eligible for the CoG

As Chuck Knoblauch’s case proves, steroids did not benefit every user. Success depended on the drugs chosen, the talent of the trainer or other individual deciding dosage and frequency, and the particular body response of the player. Even if every player in the steroid era turns out to have been taking steroids, we can’t know the degree to which the on-field results were the product of each player’s talents and training or of their trainer’s pharmaceutical skills.

Knoblauch? Garlic? Who knew?

Doom,

I checked…….Jay Gibbons and David Segui both were users with middling results. Gibbons had one good year but I believe Segui had a low-testosterone note from his doctor

Bill Dahlen, Ted Lyons and Ted Simmons. Minnie Minoso, Andy Pettitte & Ken Boyer. I’m pressed for time right now, but Dahlen was a great player; I am very surprised he’s not already in. Lyons just missed getting in yesterday, and Simmons was the fifth or sixth best hitting catcher in the 20th century—quite overlooked by both HOF voters and, so far, COG voters. Lots of great points made in the Lyons/Kevin Brown debate.

There are 45 players with 3000+ PA and a higher HR/WAR ratio than Preston Wilson. Leader is Jim Presley with a ratio of 450. Of course players with negative WAR are factored out.

I may be the only one who doesn’t buy into Ted Simmons as COG material, but that won’t stop me from presenting my reasons:

Simmons: PA 9685 WAR 50.3 dWAR 5.2 OPS+ 118

Fisk: ——–PA 9853 WAR 68.5 dWAR 17.0 OPS+ 117

Munson: —PA 5905 WAR 46.1 dWAR 11.9 OPS+ 116

Schang: —-PA 6432 WAR 45.0 dWAR 3.5 OPS+ 117

Lombardi:–PA 6352 WAR 45.9 dWAR 2.9 OPS+ 126

In terms of career length, Simmons is most comparable to Carlton Fisk, the only player listed currently in the COG. Fisk’s career WAR is 18.2 higher than Simmons, and his dWAR is over three times higher.

The trio of Munson, Schang, and Lombardi, in 2/3 of Simmons’ appearances or fewer, all came within 4-5 WAR of his total.

WAR/PA:

COG members

Bench .0086

Carter .0078

Rodriguez: .0067

Fisk .0070

Piazza .0077

Berra .0071

Dickey .0079

Cochrane .0084

Hartnett .0073

Campanella .0071

—————–

Simmons .0052

—————–

Munson .0078

Schang .0070

Lombardi .0072

Freehan .0065

Tenace .0085

Posada .0060

Bresnahan .0076

Porter .0062

Burgess .0066

Sundberg .0059

I know that long careers are worth something, so here are the WARs for the four catchers with 9000+ PAs, three in the COG:

Carter 70.1

Rodriguez 68.7

Fisk 68.5

Simmons 50.1

If Simmons came even close to the other COG catchers, I wouldn’t be making this argument, but his stats are so vastly below what the others have put up—and in truth they’re not as good by quite a bit as a number of non-COG players with shorter careers—that I have to protest.

Long careers are worth a lot. Here are some actual numbers on Simmons: in the 10 seasons from 1971 thru 1980 his OPS+ ranged from 114 to 148. After a down year in 1981, he came back with two more big years in 1982-83, delivering OPS+es of 112 and 126. In 82 & 83 Simmons drove in a combined 205 runs!! Keep in mind we’re talking 1971 to 1983 here; not 1994 to 2018. For the entire 12 seasons mentioned above Simmons averaged 92.3 RBI’s per year, AS A CATCHER!! In the seasons from 71-80, plus 82, Simmons averaged 134 games a year behind the plate. He also averaged 11 games per season at other positions, mainly first base and outfield. Nearly all of the above seasons were in the NL. It wasn’t until 1983 with Milwaukee that he logged significant playing time as a DH. SIMMONS WAS A GREAT HITTING CATCHER, WHO DESERVES OUR SERIOUS CONSIDERATION. Thanks. Bruce G.

Long careers are worth a lot. Here are some actual numbers on Simmons: in the 10 seasons from 1971 thru 1980 his OPS+ ranged from 114 to 148. After a down year in 1981, he came back with two more big years in 1982-83, delivering OPS+es of 112 and 126. In 82 & 83 Simmons drove in a combined 205 runs!! Keep in mind we’re talking 1971 to 1983 here; not 1994 to 2018. For the entire 12 seasons mentioned above Simmons averaged 92.3 RBI’s per year, AS A CATCHER!! In the seasons from 71-80, plus 82, Simmons averaged 134 games a year behind the plate. He also averaged 11 games per season at other positions, mainly first base and outfield. Nearly all of the above seasons were in the NL. It wasn’t until 1983 with Milwaukee that he logged significant playing time as a DH. Thanks. Bruce G.

Sorry that second entry occurred. I’m writing from the middle of the Pacific Ocean and the internet service is spotty. Again, my apologies. Bruce

Bruce, I think RBIs are really tricky to work with. You are right to pick RBIs as a promising element for advocacy, But in his big RBI years with St. Louis and Milwaukee, Simmons generally batted clean-up, behind Lou Brock and Reggie Smith, or Robin Yount and Paul Molitor, and this explains much of his apparent productivity. He did fine as a clean-up hitter, but 100-110 RBI under those conditions is not really outstanding. It’s great to have a catcher able to do that, of course, since teams are willing to accept lower batting productivity to get a solid catcher, but Simmons was not a good defensive catcher (he has negative Rfield, but stays in positive territory because of positional credit as a catcher). His teams were essentially making a different trade-off, accepting modest defensive contributions behind the plate to get a clean-up hitter as catcher.

Munson played in the same period as Simmons. He was considerably better defensively, and when he was placed third or fourth in the batting order in 1975-77, he, like Simmons, produced his three career years of 100+ RBI. Among current CoG members, Gary Carter, another Simmons contemporary, had four 100+ RBI seasons with even better defense than Munson. (Not to mention another Simmons contemporary: Bench.)

Simmons’ career has a lot to recommend it in terms of the CoG, but it also has problems (e.g., a number of unproductive or even below-replacement seasons and a weak defensive profile at a key position). Munson’s career, by contrast, has only the problem of his sudden death: his profile is otherwise considerably stronger than Simmons’. Simmons was a high quality player and a catcher to boot, but I think he’s not clearly over the current CoG threshold and he may not actually merit being the next catcher in.

A few years ago, Richard Chester provided me with career %RDI number (% of baserunners driven in) for 297 players with 6200 PA since 1970. Simmons ranked 21st in number of baserunners in his PA and 28th in number of PA with runners on base, but only 106th in average number of baserunners in those PA. His efficiency in driving in those runners was 19.0%, ranking 45th of those 297. So, I would say, for Simmons, RBI are a useful measuring stick, because he had an unusually high number of opportunities and because he was unusually effective in those opportunities.

Doug, This is a good corrective to my post to Bruce. Richard’s methodology can indeed make RBI a stat that can yield useful information.

The copy of the list I have only provides %RDI, not the ROB (runners on base) counts, so I may not be working from the same information as you, but there are also 297 names with Simmons 45th, so I presume the %RDI info is the same. For reasons I don’t understand, some of the names on the list don’t seem to belong in the post-1970 discussion: Jim Gilliam, Gil Hodges, Luis Aparicio, Norm Cash, Duke Snider, Larry Doby, Tommy Davis, Johnny Callison . . . Some of those players were finished by ’70, others at the ends of their careers. But the list certainly isn’t generally inclusive of players before 1970 (e.g., no Aaron or Mays), and any that slipped in with career cores in the ’60s are disadvantaged by the very low batting stats of that mini-era. Richard might fill us in, but the point I’d make is that there should be fewer than 297 names on the list, and the names that don’t belong will all be below Simmons’, so his relative standing should probably be seen as somewhat lower. (On the other hand, some names are missing: Johnny Bench’s, for example, unless I’m the one who’s missing it as I look.)

But looking at the list as it is, the question becomes how to assess Simmons’ good %RDI rate in terms of the CoG. To start with a point not in Simmons’ favor, one dimension that doesn’t change is that Simmons’ good offense was a trade-off for below average defense. Given that, and mindful that Simmons’ success relied largely on his offense, how well does being in the top, say, 15% of long-term players since 1970 match our CoG expectations? Simmons ranks #45 on the list with his 19%, but there are actually 34 players on the list with a rate of 19% — Richard includes figures to the first decimal, but if we regard that level of distinction as insignificant for this sort of assessment, Simmons can be seen as tied within a group including ##35-68. If we think about position players whose careers began after 1965, we currently have a total of 38 in the Circle. How far does Simmons’ RBI work go in moving him into that list?

On the positive side for Simmons: Munson is not on Richard’s list because he falls short of the PA cutoff. If we use the proxy of WPA and Clutch to compare the two catchers on similar grounds, Simmons does have slightly better numbers (per PA) than Munson in both categories, which aligns with his solid %RDI number. Moreover, the basic “catcher bonus” still applies to Simmons, even if his primary value was on offense: he was playing a defensive role that required special and less common skills, and that took an uncredited toll on his body. I think we’ve probably been giving catchers an implicit bonus of up to 15% or so (looking at Cochrane and Hartnett), just judging by WAR. So when we discuss Simmons’ RBI work “as a catcher,” his %RDI does have more impact on whether he would fit as the next addition to the current 38 post-1970 position players in the Circle.

I created the spreadsheet for %RDI after the end of the 2014 season. I had to use the names that showed up on the PI Batting Split-Finder. When running the PI Split-Finder for careers one cannot select the range of years played. Most of the players on the list had complete careers after 1970 but there were exceptions as you noted above. There were players such as Bench who had missing data and did not show upon the list. I did not count those PA in which the batter received a walk with ROB except for the bases loaded situation.

Richard, I think %RDI is a great contribution and I have referred to your list(s) frequently over the past year and a half.

Bob Eno: Thanks for the kind words. And I am glad somebody sees fit to use that list.The spreadsheet that I created to calculate those stats was the most complex one that I ever worked on.

I’d happily consider Munson, Schang and Lombardi in our discussions and think they do merit further conversation (Joe Torre as well). I see the point you’re making, nsb, and I can’t completely discount it. No, Simmons doesn’t measure up to the likes of Johnny Bench. But neither does Barry Larkin measure up to the standard of Honus Wagner. I don’t think that makes him unworthy of the COG; we’ve got a circle that is big enough to include more than just the slam dunk 130 WAR players. Which makes for good conversation. 🙂

NSB’

FWIW,

oWAR, age 21-30; 66%+ games at catcher. Obviously, I’ve cherry-picked his prime….

1 Johnny Bench 50.1

2 Ted Simmons 45.3

3 Joe Mauer…… 44.8

4 Mike Piazza………..42.9

5 Gary Carter…. 41.6

6 Mickey Cochrane 40.9

7 Munson……… 38.1

8 Yogi Berra….. 36.2

9 Ivan Rodriguez 36.0

10 Bill Dickey…… 35.0

OPS+, ages 21-30, 3000+ PAs, 66%+ games at catcher (1893-2018 – I’ve eliminated Buck Ewing)

1 Mike Piazza 156

2 Buster Posey 135

3 Joe Mauer 135

4 Johnny Bench 132

5 Ted Simmons 131

6 Carlton Fisk 131

7 Yogi Berra 129

8 Ernie Lombardi 129

9 Bill Dickey 129

10 Mickey Cochrane 129

I would have sworn Bench placed higher on thisa list – just behind Piazza.

Ramirez, Simmons, Sutton

Abreu, Coveleski, Irvin

Vote:

Main: Dahlin, Tiant, Wallace

Secondary: Coveleski, Irvin, Smith

Someday I’ll get Dahlen’s name right; at least this time I nailed Coveleski.

Allen, Simmons, Sutton

Coveleski, Randolph, Reuschel

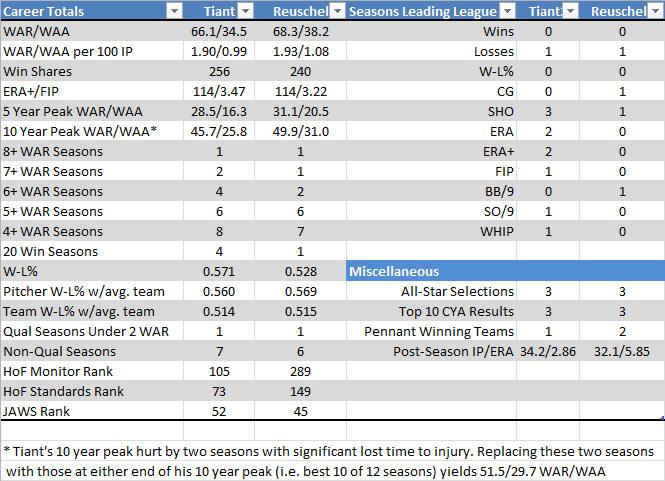

Still amazed by Reuschel’s WAR – I just didn’t see it while it was happening.

No vote from me yet – with a strong new class coming in next year, this might be the last tough vote in awhile so I want to sit with the candidates a bit. (also, I kept changing my mind in the runoff so much that I ended up deciding not to vote at all – I just couldn’t choose a single player, and didn’t want to commit a vote when I might disagree with myself an hour later).

But I’ve been reading this article series this week and thought some here might be interested so I wanted to post it. It’s a pretty interesting look into player forecasting and scouting:

https://www.theringer.com/mlb/2019/3/8/18256355/what-we-learned-from-73000-never-before-seen-mlb-scouting-reports-cincinnati-reds

The scary thing about the class next year is that the BBWAA ain’t electing 4 guys next year. We might have to drag this very good class out for a few years. Could be very interesting.

I only see two fairly obvious COG members in the 75 class, and one or two borderliners that will probably stick on some ballot or in the group of candidates we talk about during the redemption rounds. There are other cool players on the ballot that will get some discussion in remembrance but aren’t really anywhere near COG level.

If the BBWAA is willing to elects 2 of the 4-6 blatantly obvious hall non-PED associated hall candidates, that will be enough to take care of 1975 and then 76 is a down year with only Berkman worthy of even cursory consideration.

Realistically, I think you’re right that 2 is iffy and 3 a very outside shot. Jeter is a shoo-in, and while Schilling, Walker, and Rolen at least should be (if not also Jones and Helton), with 4-5 others that deserve serious consideration for the big hall.

In reality I think Schilling is 50-50 at best and Walker is less than that, and all those other guys have zero chance next year and limited chances ever. I’ll put my expectation at around 1.75: 60% that they elect at least 2 and 15% that they elect 3.

Question #8: Herman Wehmeier, ERA= 4.84

Herm Wehmeier, a name out of the past. Journeyman fourth or fifth starter/swing man for the Reds, Phils, and Cards. We’re often disposed here to talk about ‘luck’ as a negative factor for pitchers with disappointing W-L records incommensurate with high WAR and ERA+. Herm seems just the opposite. In 1948, on a team that finished 64-89, his record was 11-8 despite having an ERA of 5.86, ERA+ of 67, and WAR of -1.1.

To me, poor, misguided non-statistician that I am, these figures make absolutely no sense. The guy is credited with 17% of the team’s wins, only 9% of the team’s losses, and his WAR is -1.1. Can’t see somehow that a replacement-level player could have done better, if as well.

The main potential issue with B-R pitching WAR (per the James/Tango discussions linked in the runoff thread) is that fielding is distributed evenly, even though realistically, what each pitcher experiences from fielders is as varied as the offensive perfomance they experience. That said, if fielders were overperforming in Whemeier’s starts that would mean his WAR was too *high* and should be even more negative. And if they were underperforming, they weren’t positively contributing to wins and that would show up as an even lower ERA+. His FIP was also in line with what you’d expect from a below replacement pitcher.

So the most likely thing is that Herm experienced massive amounts of run support that year, far more than most of his teammates. I would check for that. Ok, a bit of fooling around with the game index, gave me 23 games in which Wehmeier started in 1948 (including no decisions) with an average runs scored by the Reds of 5.13. OTOH, their scoring average for the entire season was only 3.84. That’s a pretty huge differential. All but 2 of Herm’s (or the team’s on his starts) wins come with 5+ runs scored by the Reds. Then there’s one with 4 and one with 3. So he managed only one win with below average run support.

Also, of his starts, only 5 had below average run support, the rest had above average (at least 4 runs).

Compare Johnny Vandermeer, the ace who had a 115 ERA+ that year, but a similar W-L% at 17-14.

OTOH, Vandermeer faced below average run support roughly half the time, in 16 of 33 starts. He was 7-6 in games where the team scored 3 runs or less, and there were 16 of them.

If you want to know how a pitcher can have a positive W-L on a mediocre team with poor general pitching, there’s your answer right there. For whatever reason, they had plenty of offense when he was on the mound but not for everybody.

A different kind of “sequencing” when everything just happen to fall in the right place. Reminds me in the reverse of Anthony Young’s epic losing streak.

I suspect Wehmeier hung around as long as he did because he was considered a “can’t miss” prospect coming up. And, he came up pretty early, partially because of the war but probably also because he was so highly regarded (the Dodgers offered $300,000 for Wehmeier in 1948). His 1945 debut at age 18, the Reds’ youngest player that year, was forgettable (5 ER on 6 hits in 1+ IP), but also notable because he was relieved by the league’s oldest player, 46 year-old Hod Lisenbee, making the final appearance of his career and the last for any player born in the 19th century (he fared no better than Wehmeier, allowing 3 runs on 3 hits and retiring just one batter).

Part of the gaudy record was Wehmeier’s runs support. The Reds scored 5 or more runs in 9 of his 11 wins, including 8 or more runs in 5 of those games. One win came in a rain-shortened 5 innings, and another on the strength of a 6th inning relief appearance in which he faced just one batter. He also was let off the hook several times, getting an ND on four occasions when he allowed 4 or more runs in fewer than 5 IP.

For the 1974 Part 4 election, I’m voting for:

-Manny Ramirez

-Dennis Eckersley

-Andre Dawson

Other top candidates I considered highly (and/or will consider in future rounds):

-Sutton

-Tiant

-Ashburn

-Nettles

-Allen

-Wallace

-Dahlen

-Lyons

Thanks!

For the Secondary Ballot, I’m voting for:

-Todd Helton

-Willie Randolph

-Bobby Abreu

Thanks!

Has anyone tried to answer Dr. Doom’s question above, “Who is the BEST candidate on the ballot right now?”

I can’t really offer much of a statistical argument since this question is getting really difficult, with so many similar career values on the ballot. One way I look at this question is by keeping an eye on Hall of Stats’ rankings as a yardstick, and it is statistics-only (although catchers do get a bonus, and old-time pitchers get a penalty). It is mostly a mix of WAA and bWAR, so it doesn’t include comparative career value statistics at all, but here are the rankings for all players on the primary ballot if anyone is interested:

(this is Hall of Stats’ “among eligible players” ranking)

(note, there are 9 players in the top 132 of the Hall of Stats who are pre-1901 players, so the top 132 players eligible for the Cog go up to 141, and, incidentally, HoS no. 141 is Andre Dawson)

73: Bill Dahlen

74: Bobby Wallace

(91: Kevin Brown!)

93: Rick Reuschel (Secondary ballot)

108: Manny Ramirez

111: Luis Tiant

126: Graig Nettles

128: Ted Lyons

135: Willie Randolph (Secondary ballot)

139: Dennis Eckersely

141: Andre Dawson

151: Richie Ashburn

159: Dick Allen

170: Ted Simmons

175: Don Sutton

Kid, I haven’t responded because Doom, you, and everyone else here knows my answer and all my longwinded arguments. The Hall of Stats seems emphatically to agree.

Bob, due to your years of advocacy, I hereby exempt you from participation in my above question. 🙂

And Hub Kid, thank you for your fory at tackling the question.

Question 5: Roy Oswalt. .668 W-L% thru age 30, .472 W-L% from age 31 and on. Differential of .196 versus .187 for Washburn.

Main Ballot:

Ramirez

Eckersley

Simmons

Secondary Ballot:

Helton

Randolph

Minoso

Just a thought and a plea for Ken Boyer…..

Ramirez and Simmons are getting raked over the coals here for being subpar defenders. How come no love for Boyer? He won five gold gloves and has a total zone RAA of +70 at the hot corner (19th all time). He was athletic enough to have played over 100 games in center field! He won an MVP award and his hitting (while not historic) compares favorably to many others on the ballot.

OPS+

Allen 156

Ramirez 154

——————-

R.Smith 137

Helton 133

Minoso 130

Abreu 128

Irvin 125

———————-

Dawson 119

Simmons 118

H.Matsui 118

Boyer 116

———————–

Ashburn 111

Dahlen 110

Nettles 110

Wallace 105

Randolph 104

———————-

B. Molina 86

I’ve got him above Nettles, who remains on the main ballot. What gives?

Josh, Boyer is not currently getting my vote — though I’ll considering a vote change on the Secondary Ballot by Friday — but I agree with you that he is a highly viable CoG candidate. I wrote an advocacy comment for Boyer during Round 2 a few weeks ago, and I’ll stick by it.

Yes, I read it at the time and liked it. Thanks for reminding me about it. For those who may have missed it, it is well worth a read, but Bob’s main points in favor of Boyer (if I may be so bold as to summarize) were:

1) He has a higher 5 year WAR peak than any candidate on the main ballot.

2) His WAR per qualifying season trails only Dick Allen on the main ballot.

3) He played a transformative role in the way baseball was played at 3rd base, and may have been better remembered for his fielding exploits had his brother Clete and Brooks Robinson not immediately followed him onto the scene (two of the top 4 fielding 3rd basemen of all time).

4) He bests Ron Santo (a COG 3rd basemen) in WAR/PA*500 and is at his level in terms of sustained quality.

I agree he’s a viable candidate. And I think clearly, there’s a critical mass of others here that do as well, otherwise he wouldn’t have hung around on the ballot for so long.

After looking at the lifetime 3B WAR list, It seems to me that the question of whether he deserves enshrinement hinges on the comparison to two 3B ahead of him in the WAR list (nettles and Bell) and one right on his heels (Bando). One of these guys is on the ballot as an option to vote for, and the other two are in redemption discussion hell.

I think to advocate for Boyer, it’s important to say why you’d vote for him over those other three players.

Thanks for the thoughts, Michael. Bob Eno and I had a short conversation in the last voting thread about Boyer versus Nettles and I think we both had Boyer slightly ahead. It seems to me, if you’re willing to admit that Nettles (and Bell) was a better fielder than Boyer, but Boyer was the better hitter, than how much better was either player at their respective strength. For my part, I’ll take Boyer’s superior hitting and slightly worse (but still excellent) defense. But, that is a short, simplistic explanation. I am willing to be convinced otherwise.

As to Bando, I guess I’ve never had him ranked as highly as Boyer. I’d be interested to hear arguments in his favor.

Here are the stats I’d use to compare these guys:

WAR(fWAR)……….…Pk5….Top5….WAR/500PA….OPS+…Career length

61.5 (56.2)……………33.0….33.2……..3.7…………….119……….1.1………..Sal Bando

66.3 (61.7)……………30.0….31.4……..3.3…………….109……….1.4………..Buddy Bell

62.8 (54.7)..………….33.0….34.0……..3.8…….………116……….1.2………..Ken Boyer

68.0 (65.7)……………28.7.…32.2……..3.3…….………110……….1.4………..Graig Nettles

If bWAR is our guide, then Boyer prevails in peak and rate stats, exceeds his closest competition (Bando) in career length, and both Bell and Nettles in OPS+. But these four guys are very closely clustered; fWAR seems them very differently; and I think we’d need to do a much more thorough analysis to rank them with any responsibility. I did try pretty hard with Boyer and Nettles, but there was still not much to choose between them. Outside the stats, Boyer has an additional edge by being a trailblazer in the emergence of third base as a slick-fielding position, but he was so quickly eclipsed by his brother Clete and by Brooks Robinson that this is no longer a part of his reputation.

Concerning Boyer, part of the trouble is that, in his prime he was overshadowed first by Eddie Mathews, really overshadowed at the plate, and Mathews was a good glove, not spectacular. Then Santo came along, and for a couple of years during the overlap Boyer was third best at third base in the NL.

1956 and 1961, off-years for Eddie, Boyer did have a slightly higher WAR, but in his time he was never considered the equal of Mathews, not close. Was that fair? Well, Eddie had an Rbat of 506 and an Rfield of 33, Ken an Rbat of 185 and an Rfield of 73. I’d call it fair.

Somehow Mathews always seems to get left out of the third base discussion and the elite player discussion, even though only Schmidt among third basemen comes out higher on most scales and not by much. In a different era, say Schmidt’s, he might have been better appreciated. Vying against Williams and Musial from the older generation, contemporaries Mays and Mantle, and Aaron and Frank Robinson who appeared close on his heels, his bright light is outshone by too many. Playing up Boyer now without recognizing his greatly inferior overall stature compared to Eddie, though, falsifies the picture, I think.

Well, Boyer is getting played up, because he’s not getting compared to Mathews here. He’s getting compared to other borderline COG candidates. Mathews sailed into the COG and is really just a step below Schmidt, He’s got the second most WAR of anyone who played 3B for 50% of their games, and in fewer seasons and PAs than anybody that’s close. He’s probably the second best 3B of all time (even if you favor others for the #2 spot, you’d have to say it’s a close call), and I don’t think there’s any question he was better than Boyer. The question for Mathews is where he stacks up against the greats of the greats. He had to wait a couple years for COG election only because his birth year was so stacked, with Mays and Mantle ahead of him, but he went in easily ahead of Ernie Banks who was a fairly obvious COG selection, and Boyer who is still sitting on the ballot >50 elections later. Mathews is clearly not the equal of Mays. You could make an argument v. Mantle or Schmidt, but I think he comes out behind them.

But he’s clearly far and away ahead of everyone we’re debating now. And it’s not really relevant to the discussion now, since Eddie has long been enshrined, exactly where he belongs, in the Circle. We’re debating who gets in, and to do that, you just have to be about as good as the worst guy we’ve put in that wasn’t a mistake. You don’t have to be as good as the no-doubters. If you had to be as good as Eddie Mathews to make it, then the circle would have maybe 30-40 guys, and somebody like Mathews wouldn’t be a no-doubter anymore.

Michael,

here are Mathews and Boyer at or near retirement,

1893-1968, 50% of games @ 1B & 3B, WAR.

1 Lou Gehrig 112.4 1923 1939

2 Eddie Mathews 96.6 1952 1968

3 Jimmie Foxx 96.1 1925 1945

4 Johnny Mize 70.9 1936 1953

5 Ken Boyer 63.0 1955 1968

6 Home Run Baker 62.8 1908 1922

7 Hank Greenberg 57.6 1930 1947

8 Bill Terry 54.2 1923 1937

9 George Sisler 54.0 1915 1930

10 Jimmy Collins 53.3 1895 1908

11 Stan Hack 52.6 1932 1947

Quite surprised to see Boyer so high on this list; shocked to see Smiling Stan. Obviously there are a lot of guys in the middle infield as well as OF’ers who would displace this group but, I think we can see by this partial list why Mathews was regarded as an all-time great and why Boyer was so well regarded.

I dunno why Mathews wasn’t the third baseman (pie Traynor) on the all-time team in 1969

“I dunno why Mathews wasn’t the third baseman (pie Traynor) on the all-time team in 1969.” The old sportswriter crew (Lieb & Co.) was still shaping opinion — in those times, the story line that played best was that the postwar newcomers were not at all in the class of the old timers. (It’s how I was indoctrinated as a young fan.)

The reason Boyer stands out despite Mathews was that while Mathews established a new model for the third baseman as slugger (something unseen in the lively ball era) — and was much celebrated for it in his day — Boyer, who arrived only three years later brought both a bat and a very visible glove. Mathews was no slouch as a fielder, but I don’t recall it ever being seen as part of his profile; Boyer introduced the profile of the slick fielding third baseman. If brother Clete and Brooksie hadn’t come along, that reputation would have persisted.

Obviously, overall, no third baseman was in Mathews’ class till Schmidt came along. Unfortunately for Mathews, he lost his matinee idol status along with his hair, and then had to play in the shadow of his even more spectacular teammate, Mr. Aaron.

Two other well-known Eddie Mathews facts:

1. He was the only player to play for the Boston, Milwaukee, and Atlanta Braves.

2. He’ll always be the cover boy from the first-ever issue of Sports Illustrated. For my money, it’s still the best cover they’ve ever published (with an honorable mention to Vince Lombardi being carried off by Jerry Kramer).

Mathews should have been on the all time team — I wonder if it was not a function of BA still being held in high esteem. Traynor’s .320 looks pretty good next to Mathews .271. (And Traynor actually had more 100-RBI seasons too).

main:

Manny Ramirez

Dennis Eckersley

Ted Simmons

secondary;

Andy Pettitte

Minnie Minoso

Hideki Matsui

My vote is below, I promise. But I have to ramble for a bit.

Been wracking my brain on all these candidates. It seems to me that they all have such OBVIOUS weaknesses; again, this is not a surprise; we’re definitely picking guys who belong in the bottom-10 of the COG.

As I said in my earlier post, I’m really trying to start from scratch. I tried doing some of my own calculations. Whenever I do, I keep coming up with the same issue: the fact that, in my opinion, almost all of our pitchers are more qualified than almost all of our hitters. This is an almost inescapable conclusion for me. We have some fantastic hitters, but once you factor in defense, they drop like a rock; we have some defensive wizards, but their hitting isn’t up to snuff. We have one player who was HEAVILY impacted by segregation, but to what extent is unclear (and, it seems to me, becomes borderline at best even with best-case-scenario thinking). We have another who was impacted to a lesser extent by same. We have a catcher whose defensive reputation is all over the place, who becomes a lock if he’s as good as some think he was, but becomes impossible to induct if he’s as bad as his greatest detractors suggest. We have guys who straddle that 19th- and 20th-century border REALLY hard (I DO think I’ve gotten some clarity on which of the two I prefer, though, which is SOMETHING; if anyone’s interested, let me know and I’ll be happy to post about it later). I don’t really know where to go. But with the pitchers? Well, that’s easy: they were really, really good. As I showed in an earlier post, it’s not hard to calculate Don Sutton as being worth 80+ WAR, which makes him a lock. Likewise, the same back-of-the-envelope calculation for Ted Lyons makes him a 70+ WAR guy (I did not realize this until today, by the way). But then, both of them benefit from HUGE numbers of innings with performance coming mostly from above-replacement-but-below-average performance. I’m slowly coming to the conclusion that it’s entirely possible that Rick Reuschel is actually the best player on either ballot – and I was one of the primary driving forces in getting him dumped OFF the main ballot while Luis Tiant lingered on. It’s SO CONFUSING. So I’m going to do my best.

Main Ballot:

Don Sutton: I wound up an accidental advocate for him. Haven’t voted for him before, but it becomes increasingly difficult for me to avoid voting for him. My thought is this: the main thing holding him back is that baseball-reference does not believe that the teams he pitched against were expected to score very many runs. I’m not sure I can balance that against the fact that he posted excellent numbers, and that his ERA and FIP are basically spot-on, which leads me to believe he was just plain effective. He’s nobodies best starter; probably, he’d be the worst starting pitcher in the COG. But someone has to be, and it would seem somewhat fitting for Sutton to be an also-ran, even among greats.

Dick Allen: I’m very, very unsure about this pick. But I do think this: Allen had the best peak of anyone we currently have to choose among. At his best, he was the best. And for me, that’s good enough.

Andre Dawson: I’ve always wavered and waffled on Dawson, always coming to the conclusion that he’s right around the borderline. This vote, I’m choosing to push him over the line. And, frankly, it couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.

I strongly considered one of the 19th-century-I’ll-never-vote-for-him guys – seriously. I almost gave him my last spot, but I’d rather see Dawson in, and I’m not sure he’s any stronger a candidate than the others I considered. Ted Lyons, Ted Simmons, Richie Ashburn, and Manny Ramirez were the others who could’ve gotten that last spot. They could all just as easily be on my ballot as off it. I may yet change this vote; it’s just too hard.

Secondary Ballot:

Rick Reuschel: As I said above, I’m coming to believe that Rick Reuschel may be the best player on either ballot – or, if not the best, he has the performance with the fewest caveats and the easiest case to understand.

Reggie Smith: Like Reuschel, after some weekend research, I actually think Smith might be the best position player on either ballot. That’s a little more difficult to argue than Reuschel, I think, but I’d really like to see Smith in, which I wouldn’t’ve said, even last week. I’m glad I looked into it more. I have him rated as the top offensive player on the secondary ballot, AND he’s the best defender. An easy “yes.”

Monte Irvin: I really don’t know about this one. As some of you may have seen last round, Bob, mosc, and I had a nice little discussion about Irvin and his relative value to the other candidates on the ballot. On the one hand, segregation was – obviously – a travesty. I would like to see it corrected-for as much as we can. Players were robbed of higher salaries and better competition; fans were robbed of seeing the best players in the world compete on the same field at the same time; historians are robbed of making accurate comparisons. To see Irvin get some “extra credit” a la Satchel Paige and get in? That would be fine with me. On the other hand, I have NO DOUBT that Satchel Paige belongs near the top of the COG, so his inclusion is EASY. The question with Irvin is, did segregation prevent him from being a ‘yes,’ or is he really just a borderline guy, even when you adjust for segregation? And worse yet: is he even SHORT of inclusion with an adjustment? I’m not sure, but I think most likely he’s just plain not as good as some of the other guys on the ballot. My inclination here is to say that I will not fight his induction, and may actually support it… but if the group decides he simply wasn’t good enough, that’s fine, too. But after studying the issue more thoroughly, I’m unconvinced by anyone else on the secondary ballot, so it’s just Reuschel and Smith for sure, with a hard maybe on Irvin.

Todd Helton is the only other player on the secondary ballot whom I really considered, on the strength of that peak, which was marvelous. I would have no problem with him getting in, either, but I’m not going to work for it.

I agree we’re really getting down to players with serious holes in their credentials. It’s inevitable as the actual HOF seems to be voting in more players per year than the birth-years we’re going through. I agree with the general gist of your analysis. There are a couple of factors I don’t think you’re fulling considering, but those are just my personal takes on importance:

***

Non-MLB stats: We do have some negro league stats on Irvin… and they are jaw dropping. His NLB slash line is .354/.393/.532/.924 (a lot of parks without outfield walls tended to reduce raw power numbers) and that covers mostly the ripe old age of 20-22. You can say that’s a minor league type level of competition and I wouldn’t completely negate your argument but his minor league line… .375/.509/.683/1.193 over a clearly unnecessarily large sample size of 663 PA is even more comical. The point is we have a couple seasons worth of numbers that weren’t from the major leagues to look at with Irvin and they blow away his competition. Has Jersey City AAA ever seen a slugger like Irvin in ’48? They got quite a look at him. I don’t know what other 36 year old has had to spend 75 games in AA like Irvin did in 1955 but I bet they didn’t OPS 1.069. Plus the stories from the first black players in the late 40s and early 50s MLB were so utterly scary. How these guys managed to play baseball at all was inspiring.

***

MLB inflated stats: Lyons pitched segregated baseball at the height of the negro leagues. He also lead the league in ERA when many of the league’s best were already off to war in 1942. As much as I want to give him the benefit of the doubt for ’43-’45, I feel like we’re missing taking something away for his earlier career, particularly ’41 and ’42. This is also a big knock for me against Dahlen and Wallace. Related, I also adjust downward for the steroid era which hits Reuschel and Ramirez (ha!) as well as Pettitte and Abreu. These cases are all borderline, it doesn’t take much to push somebody off. Pettitte I seem to believe because of his honesty on his actual use and his post season records may well stand forever so there’s some positive swing there to counteract the negative.

***

You’re getting away from peak. Lyons and Sutton are not guys who were ever among the league’s best. They didn’t fall from a peak, they simply stuck around longer than their peers, maintaining what they had for longer. Starting pitchers acrue more replacement level value than position players, not WAA. Eck has more WAA+ than Sutton and Lyons don’t forget. I think when you compare pitchers to hitters, you have to remove some of this replacement value. The hall of bullpen saving need not apply.

I took a comparative approach at some other MiLB slash lines for contestants on this ballot:

.293/.375/.452/.827: Abreu. Certainly not rushed along by his major league line, he seemed to show the normal progression you’d expect from somebody who was ready to star at age 24 but wasn’t ready nearly as early as Irvin

.285/.369/.464/.833: Smith. Roughly a year ahead of Abreu’s pace by age, we see much the same pattern.

.289/.401/.433/.834: Randolph. Arguably a little rushed, at least with the bat, Randolph was still ready to hit MLB pitching at age 22.

.330/.417/.492/.908: Helton. Keeping in mind half of this is in Colorado Springs, Helton was right on pace for productive swinging at age 23 and grew into even more. A true first base bat, but still not a great comp.

.298/.391/.546/.937: Ramirez. Top prospect Ramirez might well be the best comp for Irvin’s early years. Ramirez dominated rookie ball at age 19 with an eye-popping 1.105 OPS and by age 21 was complete with any minor league learn-able lessons. His age 22 line was mostly held back by the ’94 strike, not learning how to hit major league pitching.

.339/.396/.605/1.001: Dawson. Half of that is in Denver, but Dawson needed very little help in his minor league career. A rough cup of coffee at age 21 didn’t slow him down as a productive big leaguer by 22.

So what did this tell me? Unless you think the negro leagues were A-ball, Irvin hit at a younger age than all these guys and none of them put up numbers in AA/AAA at younger ages that were out of line with Irvin’s negro league stats, even at older ages. Aside from their first initial 100 games or so, all of these guys transitioned to the majors with only a small decline from their younger year minor league numbers. Irvin’s age 20-22 stats line up well with a guy who would get called up and hit very well in the majors.

Thanks for those thoughts. Again, I voted for Irvin… I’m just doing so with some, what I think is healthy, skepticism.

One thing: why would Reuschel get dinged for the steroid era? I mean, I understand that he had some very good years in his late 30s, but he had as many bad ones as good ones. I don’t think it’s really THAT unusual an aging pattern, particularly for the guys of that 300-win generation, which Reuschel was a part of – or darn close to – even if he didn’t actually get to 300 wins. It just surprises me that you’d take that stance on him. Out of curiosity, do you also take that stance in regard to Nolan Ryan? Personally, I think you see the effects of steroids most beginning in 1992, and Reuschel was out of the game after 1991. I’m not denying the possibility that he used steroids; it just surprises me to see him labeled as a contemporary of Ramirez and Pettitte and Abreu (with all of whom he overlapped for a combined zero seasons), whereas he overlapped with Reggie Smith and Luis Tiant for over half his career, with Don Sutton for about 80%. He and Simmons were only shifted from one another by 3-4 seasons. Heck, Andre Dawson played WAY more in the “steroid era” than Reuschel. It just strikes me as a surprising identification, so I’m curious why you think of Reuschel so clearly in reference to steroids.

Mosc,

“” I don’t know what other 36 year old has had to spend 75 games in AA like Irvin did in 1955 but I bet they didn’t OPS 1.069.”

Check out the career of Luke Easter….he was pounding the ball into his forties:

https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=easter001lus

mosc, I’m in full agreement with your case for Irvin and there’s no question that players before 1947 were not facing as robust a talent pool as were those after segregation’s effects were significantly attenuated, say, after the late ’50s. But I’m puzzled by the way you apply the latter criterion here. You note, correctly, that Lyons “pitched segregated baseball at the height of the negro leagues.” The reason this is a problem for Lyons is not because he was personally implicated in the policy of segregation, but because the excluded talent pool was so rich in his day. In Dahlen and Wallace’s time the policy was every bit as repugnant, but, again, they were not personally implicated, and the evidence I’m aware of is that although African-Americans had formed some barnstorming teams that had good records against local white amateur teams, participation levels were not high and the standard of play did not begin to resemble the level of professional white teams until the tail end of Dahlen and Wallace’s careers, and even then among only a few black teams whose stars may have been of MLB caliber. Of course, the apparent paucity of ready African-American talent was largely a product of the way post-Civil War society had closed baseball and many, many other paths of advancement, but unlike the 1940s, baseball’s segregationist policy seems unlikely to have excluded many active greats like Irvin and Paige.

If the penalty for those playing in the segregated era is based on morality, then it would apply to all players equally — the only way not to be complicit in the exclusion of blacks from MLB was not to play MLB. But if it is based on distortions related to the incompleteness of the talent pool, then the “knock” against Dahlen and Wallace would be much smaller than would be the case for players of the segregated 1940s. Of course, you can discount because of segregation any way you wish — you have been our most articulate voice on this issue — but your phrasing does seem to pinpoint one particular assessment rationale for Lyons and then to carry it over to the turn-of-the-century players where it does not fit well.

I also want to note that you seem to suggest that Lyons’ 1941 record was tainted by a depleted wartime talent pool. 1941 was not a war year. Moreover, the depletion of MLB ranks was modest in 1942; eight of the top ten 1941 AL ERA leaders played through 1942; those were among Lyons’ chief competition when he won the ’42 crown. And, in general, most of MLB’s stars played in ’42. Bob Feller and Hank Greenberg were probably the biggest name early enlistments, but even CoG AL stars like Ted Williams, Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, and Joe Gordon played through 1942 (Johnny Mize and Stan Musial are CoG NL examples). In many respects, 1942 is the inverse of 1946, where there was some lingering impact of the War because of players who continued to be absent on active duty. It is the years 1943-45 that create the major problem in assessing MLB quality, and Lyons’ absence was one of those reasons.

Doom, you’re right. It looks like I have the years wrong on my mental image of Rick Reuschel by nearly a decade. The only real knock on him is his lack of a continuous peak, with stress on the continuous. He had a monster season in 1977 and I doubt his 85-87 success in Pittsburg was overlapped much with the roids era as I somehow remember. The ’85 pirates lost 100 games with a lack of power (ISO .100 flat) and pitching (other than Reuschel) so you’re right, we shouldn’t have any qualms attributing rebuilding his career to anything other than himself. Bonds and Bonilla didn’t show up until a little later (though they were all full-time players on the ’87 team). I guess I do like Reuschel better than the other starters on the list.

Luke Easter is a name I didn’t know. It’s a shame because it looks like another guy with loads of talent that never got to play but I guess his negro league career was just not long enough to garner the attention of the others. No pre-war baseball history seems to hurt his case as an all-time great but he certainly hit as well as most greats did at his age. Clearly not the fastest guy, I guess he’s hurt by the first base issue we’ve documented elsewhere. Irvin was certainly a more complete player. From an MLB perspective he’s somewhat similar to Irvin and does also make a nice yardstick for comparing AAA to MLB (which he shows as quite a chasm). His negro league stats line up pretty well with his MLB stats so perhaps that’s more evidence of the negro leagues being something more like quad-A in the 40s. That would also speak well for Irvin’s success there at a very young age.

Bob Eno (epm), I don’t know what to make of the worlds Lyons spans. I think of the peak of segregated baseball as like 1920-1942. Cool Pap Bell was 1922-1946, something like that. Lyons is nearly a perfect mirror 1923-1946. They could have been top rivals, instead they never faced each other at the major league level.

I voted for Lyons last round… mostly over Ramirez but that’s a different matter. I think his candidacy is tough because he has to deal with the segregation impact, the war impact (he pitched during the early war), and how to project his missed time due to service based on 42 innings in 1946 and some 1942 success against an already depleting league. I don’t know. Like everyone else we’re considering, flawed but still very good at baseball.

mosc, I was agreeing with you on the segregation issue as it applies to Lyons. My disagreement concerned Dahlen and Wallace. There are no Cool Papa Bells or Satchel Paiges that they did not face. I think Rube Foster is the peak of the competition they were spared, and we don’t have much of a basis to assess Foster as a pitcher; his fame is as an executive.

And, as I noted, the impact of the War on Lyons pitching in 1942 was minimal (in ’41 none at all); the league was not in any sense “depleted,” though if you want to call the absence of one high-profile fellow pitcher as “depleting,” then yes, Lyons won his ERA crown without Feller being present, and his ERA did not include the dangers posed by Hank Greenberg (or Cecil Travis, for that matter). These same factors “depleted” MLB for years afterwards as young players like Willie Mays served their two years and the AL’s foremost hitter volunteered to spend his seasons in Korea.I simply think it’s an error to place 1942 in a class with 1943-45.

By the way, I have not voted for Lyons this round, so far, at least. I see Lyons and Tiant as comparable in pitching and have gone back to Luis for this vote, though if Lyons seems to gain ground by Friday I may switch.

Bob, I can’t speak for mosc, but my skepticism about 19th century players has more to do with overall league quality than that they were not facing specific, known likely MLB star/HOF level performers like CPB/SP etc.

It’s just a lot easier to stand out from average or replacement level, when that level is lower because don’t have a fully professionalized league yet. By the 20s, things are starting to get much more professional, and the standard of an average and replacement player is getting better, but… That’s also exactly when the impact of segregation starts to become more apparent and obvious, as you have a ton of players in the Negro Leagues with known major league level skills that aren’t allowed to play.

There was a guy who did a study of standard deviation in results to determine overall league quality over the years, but I can only find references to it. That’s the kind of thing I’m talking about. The idea is that when a league is weaker, the difference between the best and weakest vs. the average is greater, which makes it easier (and less impressive) to rack up lots of WAA and WAR than in stronger leagues.

So WAA and WAR, as awesome as they are, clearly bias us toward standouts from times when leagues were weaker.

Consider the top players by hall rating, which is basically WAR/WAA based. I looked at all players with a 250+ Hall rating and marked what decades they played in. Then I looked at each decade (with all late 19th C as one), from 19th C through the 2000s to see how many such players were active in each decade.

And here’s the list.

1880-1899: 2

1900-1909: 6

1910-1919: 9

1920-1929: 7

1930-1939: 5

1940-1949: 2

1950-1959: 4

1960-1969: 4

1970-1979: 2

1980-1989: 2

1990-1999: 2

2000-2010: 2

There were a total of 15 players on this list — only 4 of whose careers began post integration.

Given how much professional baseball was being played in 1900-1930 vs. 1950-2010, does it really seem realistic that only *4* of the top 15 players started their careers after 1947?

Does it really seem realistic to you that there were 4 times as many of these super greats on the field in 1910-1919 as at any time since the early 1960s? 3 times as many in 1900-1909? And as many in the 19th century? Even though there were 50% more players in the 90s then in the 1910s who pitched 10 IP or had 20 PAs? And 60% more in the 2000s?

That doesn’t seem realistic to me at all. I look at this, and it seems pretty obvious to me that it was easier to stand out in pre-integration ball and that includes the deadball era and pre-deadball era, so we should probably not give those guys quite the same level of credit as we give newer players who accumulate similar WAR/WAA levels.

At the top that means I think blasphemous things like that Babe Ruth might not be the greatest player of all time. I think Cobb, Speaker, Wagner and Hornsby were probably not better than Schmidt, Morgan, Ripken and Henderson. Among pitchers, not just Roger Clemens, but plausibly Seaver, Maddux and Johnson are better than Cy Young and Walter Johnson. And I seriously mean that in terms of how they compared to their era, not absolute ability. I mean in terms of how many standard deviations they were above the average of their time.

And here’s the thing, this effect filters down to COG borderline level too. If it was easier to stand out in WAR/WAA, that means a higher percentage of guys in 1900-1930 accumulated in the 60-75 WAR range that puts you in our borderline sights. Personally, I think we should be pulling from roughly the same percentile of players in every era. This is why I’m skeptical of Dahlen and Wallace, and *also* Lyons, and why I think some of the golden era and deadball inductees are by *far* our weakest COG members. We’ve already inducted players from those eras out of proportion relative to newer ones, and I think the big reason is the WAR/WAA bias toward weaker leagues.

I’m this is clearer than my previous responses in this regard.

And this is not at all about integration, it’s about league strength — though segregation clearly was a contributed by making MLB much weaker than it could have been in the 20s-40s.

Michael, I think I understand your argument, and I recall your making it before in abbreviated form (when I used it to argue that standouts from the PED era would be similarly suspect because of the way ordinary non-PED users were operating at a comparatively non-competitive level).

When you write, “it was easier to stand out in pre-integration ball and that includes the deadball era and pre-deadball era,” I think it is not at all as clear as you intend. (I assume from the arc of your larger argument you mean more than simply that there was a growing pool of talent excluded by segregation.) I think what you’re saying is that the talents required to be outstanding were rarer in those eras than in later ones, and therefore the outstanding players stood out more easily — but the reason such talent was rarer was because it was harder to acquire. There was less opportunity to benefit from trainer-teachers; the path to the Majors was more hit and miss; the skills in question were ones that were in the process of discovery and exploitation by their initial exemplars. What you call “professionalism” of the leagues seems to me the dispersal of training opportunities, development of scouting/development paths for players, and opportunities to learn the skills that had become routine because of the performative discoveries of pioneering players. It is not “easier” to stand out in the earlier eras; the early stars were much more self-made players, and that’s hard. But, yes, the opportunities to discover routes to surpass the common player were more readily available in the earlier eras, and talent was therefore less balanced.

I don’t see this as in any way a matter of professionalism; I see it as a normal process in the development of any specialized endeavor over time. I’d guess there are many, many physicists with the genius of Einstein or Bohr today, but the opportunities for paradigm-busting breakthroughs in post-Newtonian physics are less readily available because the earlier guys exhausted some of them — the field is far more professionalized and it’s harder to stand out. I don’t think that takes anything away from Einstein and Bohr.

I’ll go back to the particularly illustrative example of Bobby Wallace and his innovation of the infielder’s throw. That can only be invented once and it was invented by Wallace — it’s at least as brilliant as, and far more fundamental than the choreography Brooks Robinson developed for third base play, on which his Hall and Circle cases rest. You could say that Wallace had it easy because he came early, before someone else patented that innovation, but coming up with the idea, putting it into practice, and performing outstanding fielding with a new and unfamiliar skill was not easy: it was very hard.

Professionalism in the sense of a commitment to perfecting skills in playing the game, on both personal and team levels, rather than simply exercising the skills you have, becomes a dominant mode only after 1890, with the conceptualization of so-called “scientific baseball,” and from that point on everything is a continuum. Of course the talent level rises, and as the game expands in popularity and its ambitions more players are attracted into or sought out in order to expand the pool. But each step is built on the improvements exemplified by the outstanding players of the step before. Apart from the period of initial integration, there is no line separating the eras, and to penalize the earlier players — whether Bill Dahlen or Babe Ruth — because their exceptional talents were expressed in an era less professionalized than the next is to exclude them from the only opportunities for greatness open to them.

And when it comes to uneven distribution over time, consider the era Lyons played in. When it comes to pitchers whose careers were anchored in the initial lively ball era (that is, 1920-1942), there are exactly four (Vance, Grove, Hubbell, and Ferrell), and one is in on a hybrid case. Compare that to pitchers spanning the “second dead-ball era” through the mid-1980s (with careers centered in 1963 to, say, 1985): we have twice as many: nine — and seven others (almost 20% of all CoG pitchers) beginning their careers within the five season span of 1984-88. Is it reasonable to believe that pitching talent just dried up with the initial home run era, or that pitchers with a normal talent distribution faced an unusually tough challenge in figuring out how to pitch in an entirely new game context, with minimal understanding of its physical toll, without wrecking their arms (as Ferrell did). If it’s the latter, then does it make sense only to penalize those pitchers for segregation during NLB’s heyday without considering whether they might not deserve a combat bonus on other grounds?

Only 17 CoG pitchers began their careers before segregation ended, from Cy Young in 1890 to Warren Spahn in 1942. We have 24 pitchers whose careers begin in the period 1948 (Roberts) to 1995 (Rivera). Even taking expansion into account, I don’t think we have failed to balance our selections more favorably than the Hall rating you have cited in your example.

Michael, reading your breakdown of league strength yesterday made me chew on a few things, both in terms of your premise and the specific applications of your analysis. I hope you’ll indulge me as I engage further with this.

First, it touches on a point that I’ve often wondered, whether WAR has the same ‘standard deviation’ effect as, say, batting average. I think I’ve mentioned before (well, maybe like a few years ago) that I use in the stats class I teach the example of batting average over time to teach standard deviation – basically the point is that the statistical reason no one hits .400 anymore is that the standard deviation of batting averages is smaller than it was in the early days, but the average is similar over time. And the likely underlying reason is that the overall player level is higher, both on the hitting and pitching side. So Altuve might be the same amount of standard deviations above average as someone like Wagner over 100 years ago, but it’s harder to get consistent hits if the overall pitcher level is great, and it’s harder to get a huge raw average advantage over other hitters if the level is so tight ie. standard deviation is smaller. That is basically what you’re saying about player WAR, yes? I have idly wondered if WAR had some kind of corrective effect that lessened this kind of distortion, but haven’t been fanatical enough to plunge through the ‘WAR explained’ pages and really dig in. If you do turn up a link to that standard deviation study, or if anyone else has better knowledge/info, spill it here! I’d be interested in learning more.

But I will say, your analysis of the top 15 players of all time according to hall rating seems to me to not be an effective way to make the point that we should discount the achievements of early players on the margins of the CoG. Firstly, why use hall rating – derivative of WAR as it is – instead of just straight up WAR? But secondly, although I agree that the top of the WAR list is heavily weighted towards early players relative to league size, I also think that is to be expected more than a skewing of marginal candidates. From a statistical standpoint, you have more to gain in raw numbers if you’re three standard deviations above the mean than two or one – so if indeed there was more spread in WAR in early days, it would make sense that it would accumulate more at the top. (eg if SD was 4 in 1900 and 3 in 2000 then a 3 SD-above replacement player would have 12 WAR vs 9 (gain of 3) vs a 1 SD-above player having 4 vs 3 (gain of 1). So that spread would benefit the most talented players more, and would be more diluted moving down the all time leaderboard. As well, I’d imagine those at the very top would be able to take advantage not only by having monster years, but by having more chances to tack on WAR at the end of a career, due to being a proven brand and therefore being a safer choice even at diminished capacity than an unproven replacement. This would allow the all time greats to compile at the end of a career. I feel like both of these things would benefit the top end more than the still-very-good-but-marginal CoG candidate.

To your central point:

“And here’s the thing, this effect filters down to COG borderline level too. If it was easier to stand out in WAR/WAA, that means a higher percentage of guys in 1900-1930 accumulated in the 60-75 WAR range that puts you in our borderline sights. Personally, I think we should be pulling from roughly the same percentile of players in every era. This is why I’m skeptical of Dahlen and Wallace, and *also* Lyons, and why I think some of the golden era and deadball inductees are by *far* our weakest COG members. We’ve already inducted players from those eras out of proportion relative to newer ones, and I think the big reason is the WAR/WAA bias toward weaker leagues.”