You may have read about MLB’s decision to officially recognize several Negro Leagues as major leagues for the 1920 to 1948 seasons. So, now the debate begins about interpreting the statistics for those players, teams and seasons.

More after the jump.

Probably the most complete source of Negro League statistics can be found at seamheads.com, including WAR metrics derived from the basic stats. Over at FiveThirtyEight.com, those WAR metrics were used in a snappy little article as the principal basis of comparison between Negro League players and those who played in what were formerly the only major leagues. I commend the article (which includes interactive stats presented with impressive and insightful graphics) to your attention. If you’re like me and know very little about the Negro Leagues, it’s a great way to be introduced to some of their star players.

Thanks to Bob Eno for suggesting this post, and for bringing the FiveThirtyEight article to my attention.

Thanks to Doug for the shout out (and for alerting me to the post).

I think I’ll have pushed up a field of daisies before sabermetrics gets its arms around integrating Negro League stats with MLB’s, but I’m sure the effort will be increasingly interesting as initial attempts to set parameters become more nuanced through competing analyses. It’s a project so much more constructive than, say, trying to work on comparability measures in light of PEDs. I wonder if a subgroup of sabermetricians will make a specialty of this project and give the rest of us more tools to work with.

Now that MLB has made this merger of stats official policy, it could ultimately have impact on Circle of Greats discussions. HHS contributors like mosc have led discussion on the need to discount the records of MLB players pre-1947 (and for the transition period after) vs. post-integration baseball; perhaps the seamheads.com database provides some initial glimpse into figuring out what that would mean for individual careers.

Had there been a more “enthusiastic” reception by major league teams to integration, there might be a reasonable body of data to work with in determining how to normalize negro league and major league stats, using the statistics of players with careers straddling that period. Sadly, the slow pace of integration by many major league teams really leaves us with relatively few such examples, making the task of normalization all the more difficult.

Doug,

Normalization is an impossibility. Stats are sketchy….rosters were thin. Even if we all agreed that Satchel Paige was the greatest of all time regardless of skin pigmentation, from a statistical perspective, are his “normalized” numbers (W-L, ERA, ERA+, SO/BB, etc….) more like Grove, Feller, Johnson, Spahn, Seaver, or Maddux?

Maybe the more universal good of righting a historic wrong is more important than trying to make fine gradations on stats.

MLB and corporate America are in the same boat and (IMO) merely looking to avoid boycotts and cancel culture. I seriously doubt either’s sincerity in any of this recent “onboarding”

I’m not really sure what Manfred’s intent here was, but there’s no doubt in my mind that segregation was a moral wrong. Personally, I’d be more focussed on correcting it going forward than trying to create an equivalence in the past through gestures.

Mike L

I’m sure that as individual US citizens we all agree that segregation is morally wrong, however, I have reservations about corporate America and MLB being concerned about anything beyond the bottom line. Maybe I’m naive (or half-blind) but I believe the majority of segregation nowadays in the US suburbs and urban areas is due to monetary/economic differences and not flat-out racism. (Sorry, I can’t call them inequities).

Specifically, I was talking about segregation in baseball and not housing. As to the rest of it, I’d repeat what I said above, which is that gestures about the past are just that. Sports is a business, but it’s also a niche business which markets its past as a core part of its DNA–places like the Hall of Fame are examples. MLB is making a business decision as much as a “moral” one to do this.

Bob, would you be concerned that suggesting a “correction” rubric might actually support an adverse inference–try too hard to normalize, and the entire project looks too synthetic and diminishes all?

Hi Mike – Well, first off, I hadn’t meant to argue that integrating the stats was a good thing, just that it was going to happen and that I was sure it would be interesting to see how the process is handled by people with skills in baseball history and stats. Paul says above that normalization is an impossibility, but I think what he meant might have been that it can’t be done well. I don’t have any doubt that there will be multiple competing models for normalization. I expect that ones more complete in considering the changing historical details outside the stats will tend to be more convincing than purely formulaic approaches, and just the perception of “better normalization” will persuade people to continue looking for the “best.” I think Paul’s correct: the best will fall far short of being compelling, but I’d guess that in a decade that simply won’t matter to people as much as continuing to work on improved models.

As for over-correction: when I was a regular participant in HHS I was concerned that we had already encountered a massive and unexamined correction rubric when we debated pre-1947 CoG candidates, and some of them lost critical votes because they played during MLB’s segregated era because of it. Obviously, none of those candidates was a superstar in the Cobb/Mathewson mode, and the point that a correction was needed was absolutely valid, but the correction was intuitive, not based on data, and applied uniformly, regardless of the fact that segregation may have lowered the quality of MLB play to different degrees during different eras, depending on how many talented Black players there actually were to be excluded. There was no way to think through whether we had begun to rule out players with strong WARs at the appropriate cutoff point, both in terms of their WAR and in terms of the quantity and quality of existing competition that segregation spared them from facing.

It’s hard to imagine that the Seamheads data, even if improved, is going to allow for precise formulas for discounting MLB stats during the period they cover (which is itself limited), but if normalization formulas begin to compete, CoG arguments about whether, say, Ted Lyons belongs in or out, can go beyond a data-free judgment, which, it seemed to me, had begun to draw a line at a fairly arbitrary place.

(Just in case anyone had forgotten how long-winded I am . . .)

Since Bob Eno has made a brief reappearance, I’ll chime in, too.

I’ve been dreading the raising of this topic here ever since its appearance on the national scene. Why? I don’t think anyone can honestly claim to be able to interpret the stats available at Seamheads 1) in any way approaching an impartial manner as far as comparing is concerned; 2) in any way that can possibly allow for the irregularities of scheduling, season length, availability of reliable box scores or any box scores at all; 3) in any way that accounts for the fluctuations of roster players and the impact of such on the quality of play.

Here’s just one additional quibble—two pronged—concerning a specific soon to be famous statistic: Josh Gibson’s .441 BA in 1943. First quibble: It was achieved playing in”Multiple leagues.” Second and more relevant quibble:

G 78…PA 342…AB 281…H 124…BA .441.

This line has been touted as a new standard. But what about this line:

G 87…PA 384…AB 319…H 143…BA .448? (Rogers Hornsby in Jun-Jul-Aug 1924)

Or this one:

G 60…PA 276…AB 242…H 111…BA .459? (George Brett in Jun-Jul-Aug 1980)

I doubt there is a way to reconcile the problems inherent in coming to a realistic assessment of the issue, in any event, and I dread the inevitability that attempts to do so lie in the future.

It’s been a long time since we were on the same string, nsb. I was dismayed when you announced you didn’t plan to continue posting comments, and your comment here illustrates why: as always, your points are all good.

But one of your valid points is that while we can see the difficulties of integrating these incommensurable stats, it’s inevitable that attempts to do so will be coming our way. As I wrote in response to Mike’s comment, I think that after a while we’ll start to become interested in how clumsy initial attempts are superseded by increasingly nuanced analyses, ones that take examples such as the ones you present as challenges to be solved by combinations of historical research–ones that more fully illuminate contexts of play–new ways to formulate existing data that may yield restricted ranges where comparisons are more valid, and analyses of how such more reliable areas of comparison could be extrapolated to arrive at more universal measures of value.

Like you, I can’t really picture how this will happen, and Doug’s response to my initial comment highlights how history has cut off the easiest road to take. But I’m sure people will try, that a few will be really good at it, and that their work will foreclose the option of giving up.

I find this to be a fascinating and complicated topic as well, and I’m compelled to respond to the thoughts you’ve laid out here nsb (no offense taken if you limit your comeback to one comment and respond no further, was nice to read your thoughts).

I see two strains of critique in what you’re saying – first, the ‘it’s not the band I hate, it’s their fans’ critique of the integration of these statistics and the effect it will have on arguments. I, too, dislike the possibility that someone will interpret statistics with too much simplicity and lack of context. I’m fascinated by WAR and discussions around it – the development of that stat is a double edged sword, in that it mostly confirms the eye test of who we thought was good before it existed and also shines a spotlight on players whose parts were not as flashy as the WAR total attached to their sum, which I think adds a lot of value to baseball discussion. But on the other hand, having a catch-all comparative stat is a crutch for many, which can lead to some lazy analysis in player evaluation. I have had to remind myself of this in my own analysis, and have tried to interact with that stat as a way to draw my attention to the elements behind it, to give them a closer look, and to couch a player’s stats in the totality of who that player and person was.

So, on that front, I am a) somewhat worried about being annoyed by people interpreting these new stats without context, and b) excited that their acceptance will open new and interesting doors through which we can explore great players and games and seasons that tell a story about baseball history, in a way that hasn’t yet been told.

The other strain of critique I see is: if records coming from these stats are accepted, it would cheapen the meaning of major league records. On that front, I have a diverging opinion.

Definitely, Josh Gibson got a .441 batting average in a number of games that is a small sample size, and is not a standardized season against easily measurable competition. Putting aside the reasons that it was not possible for that to happen (for now; I’ll pick it up in a few paragraphs), I’m interested in exploring what makes Hugh Duffy’s mark of .440 in 1894 – the current Major League record – more reliable and sanctified than Gibson’s .441. No doubt it happened in just over 1.5 times as many games as Gibson (125 of them), and it happened against a stable crop of National League teams (well, relatively – the NL in the 1890s had its own volatility to be sure). That is what I can muster in defense of this record. But, like… Hugh Duffy? I think that Hornsby and Brett were both far better players than Duffy, as was Gibson. Brett got unlucky enough to come at a later era where the standard deviation of player quality was so much tighter that it was impossible to hit above .400 over the course of a season due to the higher average quality of pitching (and hitting), and Hornsby was unlucky enough to be just enough later than 1894 that the league had professionalized to the point where it was pretty tough to reach .440. Gibson was luckier in the standard deviation respect, but unluckier with regards to things that had much greater consequence to his opportunities in baseball and beyond. I like records and stats, and am used to being able to depend on numbers, so it’s weird to see leaderboards change decades after the fact. But defending Hugh Duffy’s batting average record is too much of a slippery slope for me to make it my hill to die on.

When I look at other rate stats, I’m faced with similar ambivalence. OBP, SLG, OPS are all owned by Barry Lamar Bonds in the 2000s, ERA and ERA+ by Tim Keefe in 1880, WAR (which is kinda a hybrid rate and counting stat) is currently Ol Hoss Radbourn… these make the issues with Gibson seem less absolute to me, with regards to how they affect single season records.

And when considering the greater context, that just throws more complications onto it. I have never heard anyone here say anything other than the that segregation in baseball was unambigously awful and morally wrong. So… why is it right that the stats from those games not be recognized? This is a sincere question, not a rhetorical one. I am curious what the reasons one would have for this might be. The argument I see is that it might lead to some people talking about a record as if it occurred outside the context of a small sample size and a league with poorly kept records. But I think – mostly – people look at leaderboards with Duffy and Radbourn and Keefe and Bonds with the appropriate contextualization, and so I feel like on the whole people will be able to do that with this record as well. So I don’t really find it a compelling argument, personally.

Yeah, for sure Gibson’s or Paige’s or Charleston’s stats are going to be limited by what is available in the newspaper archives and what people have recorded, and the setup of ‘league’ play was far less standardized than the white major leagues. That was, if not intentional on the part of any one person, by design of the system. As a result, the top white ballplayers of that era benefit greatly in their counting stats against inferior competition than if everyone was allowed to play, compared with those who were forced to play elsewhere against inferior competition than if everyone was allowed to play. So in the grand scheme of things, I feel like due to the limited nature of stats from games, nobody who played the bulk of their career in the Negro Leagues is going to come close to any counting stat record, and if there are a few rate stats that favour the small and unstable sample size from which they were drawn, that is a very small concession from white baseball, and a more than appropriate constant reminder of the reasons why that is a record. Josh Gibson almost certainly would not have batted .441 in MLB, but why should the burden of that continue to fall on him rather than the institution and system that everyone agrees was unjust? It seems to me a benefit to baseball as a whole to have that mark stand out as a record, as a reminder of why it’s a record.

Two thought experiments I am interested in that I believe might have some relevance to how people approach this topic:

1) Who do you consider as having the single season home run record? And why would you defend that number as the record?

2) If someone had achieved a league record for batting average in the 2020 season, would you argue that the season should be thrown out of the major league records? Would you have argued that it should remain, but should be contextualized by an asterisk or some other formal marker? Or something else? Why?

And how do you think these situations differ from the one we are discussing re: Gibson, if they do? I’m genuinely interested in hearing and respect everyone’s opinion even if I have a different one.

I dropped back in just in case any of my earlier comments had generated a reply that I ought to acknowledge, and although there were none, I’ve been treated to one of the most thoughtful and provocative posts I’ve ever seen on HHS.

I think what bells is doing is suggesting that when we play with statistics, we’re capable of elevating our level of play and, in fact, routinely do so. The function of simple stats, like leader boards, isn’t the end of play: they’re something we play with when we add the high heat of interpretation, which is really what makes HHS interesting.

I don’t think we need an asterisk to know that one will always hover beside Bonds’s home run numbers, and no discussion of his accomplishments will ever be free of it. Advanced stats try to incorporate as many of those asterisks as possible, but they are ultimately speculative and there are also non-quantifiable asterisks they’re forced to exclude (PEDs being an example). But we can handle them, well or poorly, through knowledge of historical contexts, interpretation, and argument, even when there is, in principle, no way to adjudicate two strong but conflicting arguments.

So, thinking about it in light of the issues bells raises, when I first looked at the Negro League stats, I had the sort of reaction that Paul E. and nsb had. In nsb’s terms, I thought, “I knew this was coming but it makes my heart sink to see it,” and, like Paul, I thought, “These can’t be normalized.”

But really what I was thinking was that there was no way I was capable of elevating my level of play to work with those stats. My second thought was the equivalent of, “I don’t have to elevate my level of play that far (and, after all, I’m not even very good playing with ordinary stats), I just have to wait till others who are capable of elevating the level of play do it for a while; they’ll work things out to the point where new tools let people like me participate.”

And, after all, there’s a fundamental flaw in not engaging in this work. We know beyond doubt that there were Negro League players whose play should be reflected on the leader boards–that without them the MLB leader boards don’t mean what they appear to mean: a ranking of GOATs. They are all asterisked as they stand. We’ve been content to let that be because figuring out how to rectify it seemed too hard. It is too hard, but even the initial attempts will yield results that have less profound asterisks than what we have now, and they’ll keep getting better.

bells said this better and with illuminating specifics. Terrific post, bells!

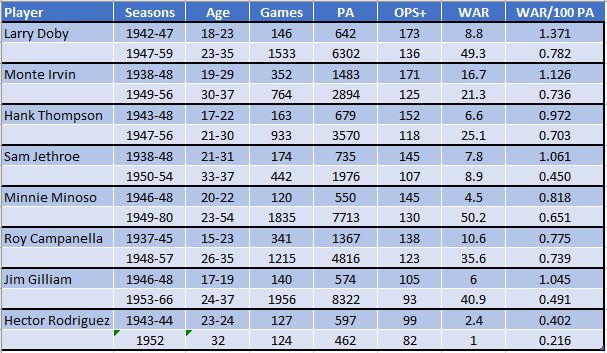

Under the heading of For What It’s Worth, these are the only position players I could find with 100 MLB games and 100 Negro League games up to 1948. Only two of the eight players had much more than a major league season’s worth of games in the Negro Leagues.

Doug, that table reminds me of how old I am getting. Striking to see Jim Gilliam, who I saw play in the mid 1960’s when the Dodgers were constantly in the World Series or on Game of the Week, was a Negro League player in 1946-48.

Gilliam’s stat line for 1946-48 is instructive, with 105 OPS+ yielding 6 WAR in fewer than 600 PA. He must have been a hell of a defender, or (more likely) there was a huge drop-off between average and replacement level players.

Thinned out rosters after WWII was over?

By way of comparison, Randy Johnson (2.9 WAR, 1982-84) has the most career WAR with less than 600 PA and 105 OPS+ or lower. For single seasons, Mark Belanger (6.5 WAR, 1976) and Lance Johnson (6.1 WAR, 1993) have the most WAR with the same criteria, and 15 other players have 5 WAR or more in such a season. But, only one of those (Willie Randolph, 1976) was under 25 when he did it, whereas Gilliam was a teenager.

Some random factoids on these eight players.

Doby – first player (1952) to lead his league in SO and Runs, with 100+ of each

Irvin – last NL player (1951) to make post-season debut with 4 hits in a World Series game

Thompson – last NL player (1950) with two IPHR in a game

Jethroe – only modern era player with 100 R and 35 SB in each of first two seasons

Minoso – last player (1954) to lead his league in TB with fewer than both 20 HR and 30 doubles

Campanella – first catcher with multiple seasons of 30 HR, 100 RBI and 150 OPS+ (only Piazza has done so since)

Gilliam – last player (1953) to lead NL in triples in debut season

Rodriguez – oldest AL rookie (age 32) with 100 games at 3B

Curious that the Giants and Dodgers were leaders in integration, but the other New York club was a laggard.

It appears that Yankees’ GM, George Weiss, was the main reason they were slow to integrate. Yankees’ owners Dan Topping and Del Webb let him run the club while they remained in the background. Weiss had a cold-hearted personality. Curiously Topping also owned a team of the same name in the All-America Football Conference from 1946-1949 and he had no qualms about African-American Buddy Young being on the team.

During Weiss’ 13 full years as the Yankees’ general manager from October 1947 to October 1960, the team won ten AL pennants and seven more World Series titles, compiling a regular-season record of 1,243–756 (.622 W-L %). Maybe he figured. “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”? I dunno

Buddy Young could fly 🙂

Doug,

Is this a lack of statistical information or did these guys really only play 40 games per season in the Negro Leagues? If the latter, they must have played a ton of ‘exhibition’ games or their skill sets couldn’t have improved much.

Re Gilliam, by “debut” season, I imagine you don’t necessarily mean “rookie” year. Richie Allen led the NL in triples with 13 in 1964 – his ‘rookie’ year. He had 24 PA’s in 1963…?

Yes, I meant first season, not rookie year.

As to Negro league seasons, Seamheads says their database is built from the ground up, so all of their season totals are based on contemporary box scores and game accounts. None of their totals are based on season totals that might be published elsewhere. So, presumably, those totals (on Seamheads) will increase as time and resources permit.

That said, I really don’t know how many games Negro league teams typically played; I would imagine most games were on weekends to accommodate players on visiting teams who had, or wanted to have, other day jobs (which I would guess would be most players).

For those who may be interested, I have updated a post from 5 years ago on batteries with 200 game starts together. You can find the revised article here.

Not on your list is Dazzy Vance/Hank DeBerry with 246 starts together. Vance started 349 games so the percentage is 70.5%. Check me out.

Thanks, I will check it out.

DeBerry’s 1926 season is notable. His .383 SLG that year is the highest without a HR of any player scoring in less than 15% of 40+ TOB (w/o ROE).

You got it exactly right, Richard. 246 starts.

But, it wasn’t 70.5%. For the seasons they were active, Vance started only 275 games. So, DeBerry was his catcher in 89.5% of Vance’s starts, the biggest number of the group, And, Vance was DeBerry’s pitcher in 48.6% of DeBerry’s starts. That is the ultimate personal catcher.

My spreadsheet shows 37920 starting pitcher/starting catcher combinations, AL, NL and FL from 1901-2019.

So, that was the only one I missed?

37919/37920= 99.997%, not bad at all. Actually 97920, due to missing data, is a fraction of 1% on the low side.