This post is for voting and discussion in the 140th round of balloting for the Circle of Greats (COG). This is the last of three rounds of balloting adds to the list of candidates eligible to receive your votes those players born in 1979. Rules and lists are after the jump.

The new group of 1979-born players, in order to join the eligible list, must, as usual, have played at least 10 seasons in the major leagues or generated at least 20 Wins Above Replacement (“WAR”, as calculated by baseball-reference.com, and for this purpose meaning 20 total WAR for everyday players and 20 pitching WAR for pitchers). This group of 1979-born candidates, comprising those with R-Z surnames, joins the eligible holdovers from previous rounds to comprise the full list of players eligible to appear on your ballots.

In addition to voting for COG election among players on the main ballot, there will be also be voting for elevation to the main ballot among players on the secondary ballot. For the main ballot election, voters must select three and only three eligible players, with the one player appearing on the most ballots cast in the round inducted into the Circle of Greats. For the secondary ballot election, voters may select up to three eligible players, with the one player appearing on the most ballots cast elevated to the main ballot for the next COG election round. In the case of ties, a runoff election round will be held for COG election, while a tie-breaking process will be followed to determine the secondary ballot winner.

Players who fail to win either ballot but appear on half or more of the ballots that are cast win four added future rounds of ballot eligibility. Players who appear on 25% or more of the ballots cast, but less than 50%, earn two added future rounds of ballot eligibility. One additional round of eligibility is earned by any player who appears on at least 10% of the ballots cast or, for the main ballot only, any player finishing in the top 9 (including ties) in ballot appearances. Holdover candidates on the main ballot who exhaust their eligibility will drop to the secondary ballot for the next COG election round, as will first time main ballot candidates who attract one or more votes but do not earn additional main ballot eligibility. Secondary ballot candidates who exhaust their eligibility will drop from that ballot, but will become eligible for possible reinstatement in a future Redemption round election.

All voting for this round closes at 11:59 PM EST Sunday, February 25th, while changes to previously cast ballots are allowed until 11:59 PM EST Friday, February 23rd.

If you’d like to follow the vote tally, and/or check to make sure I’ve recorded your vote correctly, you can see my ballot-counting spreadsheet for this round here: COG 1979 Part 3 Vote Tally. I’ll be updating the spreadsheet periodically with the latest votes. Initially, there is a row in the spreadsheet for every voter who has cast a ballot in any of the past rounds, but new voters are entirely welcome — new voters will be added to the spreadsheet as their ballots are submitted. Also in the spreadsheet is a column for each of the holdover candidates; additional player columns from the new born-in-1979 group will be added to the spreadsheet as votes are cast for them.

Choose your three players, for both the main and secondary ballots, from the lists below of eligible players. The current holdovers are listed in order of the number of future rounds (including this one) through which they are assured eligibility, and alphabetically when the future eligibility number is the same. The 1979 birth-year players are listed below in order of the number of seasons each played in the majors, and alphabetically among players with the same number of seasons played.

Holdovers:

| MAIN BALLOT | ELIGIBILITY | SECONDARY BALLOT | ELIGIBILITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dick Allen | 9 rounds | Billy Williams | 5 rounds |

| Vladimir Guerrero | 6 rounds | Bobby Abreu | 4 rounds |

| David Ortiz | 4 rounds | Ken Boyer | 4 rounds |

| Gary Sheffield | 3 rounds | Richie Ashburn | 2 rounds |

| Luis Tiant | 3 rounds | Stan Coveleski | 2 rounds |

| Bobby Wallace | 3 rounds | Andre Dawson | 2 rounds |

| Ted Lyons | 2 rounds | Don Drysdale | 2 rounds |

| Willie Randolph | 2 rounds | Andruw Jones | 2 rounds |

| Scott Rolen | 2 rounds | Monte Irvin | 2 rounds |

| Todd Helton | this round ONLY | Don Sutton | 2 rounds |

| Minnie Minoso | this round ONLY | Reggie Smith | this round ONLY |

| Ted Simmons | this round ONLY | ||

| Chase Utley | this round ONLY |

Everyday Players (born in 1979, R-Z surname, ten or more seasons played in the major leagues or at least 20 WAR):

Juan Uribe

Jayson Werth

Ramón Santiago

Carlos Ruiz

Josh Willingham

Kevin Youkilis

Pitchers (born in 1979, R-Z surname, ten or more seasons played in the major leagues or at least 20 WAR):

Rafael Soriano

Chris Young

Johan Santana

Wandy Rodríguez

Brad Ziegler

Juan Rincón

Brandon Webb

As is our custom, here are quiz questions for each of the new players on the ballot.

1. Juan Uribe played over 15 post-season games at both SS and 3B. Which other player has done the same? (Manny Machado)

2. Jayson Werth posted 1.361 OPS for the Phillies in the 2008 World Series. Which Phillie outfielder posted a higher OPS in a single World Series (min. 15 PA)? (Lenny Dykstra, 1993)

3. Ramón Santiago’s 59 OPS+ in 2003 is tied with several players for the lowest mark by a Tiger in a qualified season (modern definition). Which of those players recorded the lowest career OPS+ among All-Stars with 5000+ PA careers? (Ed Brinkman)

4. Carlos Ruiz teamed with Cole Hamels to form the most durable battery in Phillies history, with 207 regular season starts together. Whose franchise record did Ruiz and Hamels break? (Pete Alexander/Bill Killefer, 191 starts)

5. Josh Willingham recorded 5 qualified seasons in his career, all of them with 20 HR, 25 doubles, 50 walks and 10 HBP, and is the only player to post such seasons for four different franchises. Which player recorded the most such seasons in a career? (Carlos Delgado, 1998-2007)

6. Kevin Youkilis recorded consecutive 400+ PA seasons (2009-10) slashing .300/.400/.500 for Boston. Which player recorded the longest streak of such seasons by a Red Sox first baseman? (Mo Vaughn, 1996-98)

7. Rafael Soriano is one of seven pitchers to record a 40 save season for three different franchises. Who was the first pitcher to do this? (Jeff Reardon, 1991)

8. Chris Young is one of eight Padre pitchers to record consecutive seasons with 30 starts and 3 WAR. Which two of those pitchers accomplished this feat in the same seasons? (Bruce Hurst/Ed Whitson, 1989-90)

9. Johan Santana is the only pitcher with three consecutive seasons (2004-06) leading his league in WHIP, ERA+ and SO/9. Which pitcher recorded the most seasons leading his league in all three of those categories? (Pedro Martinez, 5 seasons)

10. Brad Ziegler is the only pitcher with top 10 career ranks in ERA, ERA+ and HR/9, among retired relievers with 500+ game careers. Ziegler’s 390 ERA+ in 2008 is the best in any 50+ IP debut season. Which pitcher has the top ERA+ in a 50+ IP rookie season? (Rob Murphy, 1986)

11. Wandy Rodríguez recorded a 37 point improvement in his ERA+ from his first three seasons to his next three campaigns, the fourth largest such increase among starting pitchers with 300+ IP in both periods and with ERA+ under 90 in the first. Which of those pitchers recorded the largest such ERA+ improvement? (Jake Arrieta, 73 points)

12. Juan Rincón recorded four straight 70+ IP seasons (2003-06) for Minnesota. Which pitcher recorded the only longer streak of such seasons by a Twins reliever? (Al Worthington, 1964-68)

13. Brandon Webb posted a qualified 125 ERA+ in each of his first six seasons. Which other modern era pitcher did the same? (Mordecai Brown, 1903-10)

And, a couple of unanswered quiz questions from last week’s post.

14. Dan Johnson posted 7 consecutive seasons (2008-15) of 40 or fewer games, playing first base in all of them. Which player has the only longer streak of such seasons? (Russ Morman, 8 consecutive seasons 1988-91, 1994-97)

15. Jon Garland was a CG winner in his first post-season game, allowing 2 runs on 4 hits. Who is the last pitcher to allow more than 2 runs in a CG win in his post-season debut? (Gaylord Perry, 1971 NLCS)

I propose that after this round, we have a 2nd Chance round. A ballot where anyone who has ever stayed for more than one round on the main or secondary ballots is given a chance to get back into the discussion.

Just in the last two weeks we have lost Berkman and Nettles.

Perhaps the system is perfect as it is, and the guys who have fallen off are right where they should be.

But as we are not as active as we used to be, it would give us something to do, while we still have the momentum of this year’s COG voting…

Yes, we could do that. Would like to keep the Secondary ballot to 15 or fewer players, so we do have room to add a few names.

I’ve been thinking that perhaps we should give Holdover players demoted to the Secondary ballot at least two seasons of eligibility on that ballot, rather than the current one. Basically, give them some credit for making it onto the Primary ballot, and more opportunity to get back there. Any thoughts on that?

Johan certainly has a case for the COG, even with 51.7 WAR.

Averaged 7.1 WAR over his 5 year peak.

23rd in WAR7adj, tied with Spahn and Vance

(Top 7 seasons, stat maxes out seasons at 250 IP, to neutralize the 19th century innings monsters).

Only 16 pitchers have more top 5 CY votes.

In his peak from 2004-2008, he was arguably the greatest pitcher in the world, as that half decade was at the tail end of the careers of Clemens, R Johnson, Schilling, and Pedro.

Here is the bottom of the WAR list for our COG Starting Pitchers:

57.2 Mordecai Brown (58.3 incl offense)

53.5 Edward Ford (57.0)

53.1 Sanford Koufax (48.9)

51.1 Johan Santana (51.7)

48.8 Wesley Ferrell (60.1)

47.0 Leroy Paige (47.0)

On Santana:

A quick glance at his career and stats makes him appear superficially similar to Koufax: Not as erratic early on, breakout season as a starter at age 25, performing exceptionally for seven years to Sandy’’s six, career truncated by injury. Lots of strikeouts, excellent FIP and WHIP.

He was a better pitcher in his early twenties than Koufax was, but went out with his career in somewhat of a decline, whereas Koufax retired at his peak.

The fact that he spent just one year in the HOF ballot sweepstakes strikes me as an absurdity, even given the relative shortness of his career, which is not to say that he is necessarily Hall of Fame worthy.

Despite all that, it’s hard to consider the two as really similar pitchers. A subject I don’t recall ever being addressed years ago, even though Koufax wasn’t the COG shoo-in one might have expected, was that his Dodger Stadium stats are unreal: in 86 games, all but one as a starter, his ERA was 1.37. His away ERAs during those five years were 3.53, 2.31, 2,93, 2.72, and 1.96. All the noise made by the detractors of Whitey Ford because he was a lefty in Yankee Stadium—career Home/Road ERAs, 2.58/2,94—seems a little overblown given Koufax’s domination at the LA venue. As for Santana’s ERA splits, they aren’t far off from Ford’s, 3.04/3.39, although he pitched for two teams and in four stadiums as a Met.

Another huge difference one has to consider is that Koufax in his maturity played in an era of pitching dominance. Santana had no such luck. To counterbalance that, however, Koufax started every four days in his prime and was expected to go deep into the game if not to complete it. Santana started every five days and seldom went past the seventh inning, often not past the sixth, even when he was ahead, thanks to pitch count theory.

Does this ambiguity indicate that that Santana might be a superior COG candidate to Lyons or Tiant or at least of equal consideration?

The problem, despite the supposed bullet-proof reliability of modern statistical approaches like WAR and ERA+, is that baseball players are or were living, breathing individuals, not robots off an assembly line, and they each played in situations and environments unique to themselves. Lyons did remarkable things late in his career; Tiant reinvented himself after nearly dropping from sight; for five years Santana shone like a nova in the Minnesota sky. Does that relatively brief brightness equal or better the duller but more prolonged illuminations of the other two? Do his 2025 innings match the 3486 of Tiant or best the 4161 of Lyons in terms of quality? And what about ambient circumstances, such as the fact that Lyons played most of his career for teams with losing records, some of them abysmal? WAR, I believe, is supposed to have that issue all figured out, no ambient circumstances need apply, but I don’t think that’s a realistic assessment. It’s an assessment made by people who have a great deal of experience with numbers, but who probably have never played team sports like baseball much, if at all.

Santana’s uniqueness makes him interesting enough to look at seriously at least.

Wonderful analysis, nsb, as usual. It’s good to see you and Voomo going at in-depth analysis and advocacy, which is what made CoG voting strings so interesting.

Santana definitely requires you to think whether “greatness” is best measured by peak value or cumulative career value.

Adam Darowski’s Hall of Stats uses a methodology to distinguish these two components of greatness, and then combines the two into a single score. In Santana’s case, that score is 108 (where 100 = HoF-worthy), with 64% of the score resulting from peak performance. Sandy Koufax scores 102, with 54% resulting from peak performance.

Adam announced at the end of December that he will no longer be updating the Hall of Stats database. The above link is a database archive current to the end of the 2022 season.

# 4) Robin Roberts/Stan Lopata ? (Carlton didn’t like pitching to Boone and preferred McCarver – I just don’t think McCarver played enough with the Phillies)

Here’s what I came up with:

Carlton/Boone 146 games

Roberts/Lopata 136 games

Roberts/Seminick 126 games

It’s none of those.

How about Lonborg/Boone, 155 games?

Not them.

Pete Alexander and Bill Killefer 1911-1917? (and then some more with the Cubs)

Well done, Paul. You can read more about Alexander and Killefer in my post about 200 game batteries, now updated to show Wainwright and Molina as the most prolific battery of the modern era.

In unloading Alexander and Killefer to the Cubs, the Phillies were evidently following the example of the other Philadelphia team in trading away their best players after winning a championship, albeit two seasons removed. In exchange for those two, the Phils got immortals Pickles Dilhoefer and Mike Prendergast. They got one season of league average pitching from the latter, and all of five games from the former before packaging him with Milt Stock and Dixie Davis for three players. Stock was just entering his prime and gave the Cardinals 5 solid seasons at 3rd base, and Davis provided the Browns with 6 seasons of slightly above league average pitching. The only value for the Phillies from the three players they received was when one (Doug Baird) was traded to the Cardinals for Lee Meadows who would give the Phillies three seasons of 110 ERA+ pitching.

The Phillies threw away Jenkins and Sandberg. And, their hands were sort of forced when they dealt Allen and Rolen to the Cards….

Doug: I came up with 199 games for Alexander/Killefer.

These are the games I found on B-R.

I did more research and then realized that 199 games is in error and the answer is what you found. I created a spreadsheet that identifies starting batteries but something is awry.

I found 149 games for Carlton/McCarver

Tuna,

All with the Phillies? or some STL?

Only with the Phils.

Yes, as Doug mentioned, I only looked at their time together with the Phillies.

#2) Lenny “Nails” Dykstra in 1993 (1.413)

For #7 I got Jeff Reardon who did it while on the Red Sox in1991

Reardon is correct, recording 40 save seasons with the Expos, Twins and Red Sox. In his last season in Boston (1992), Reardon passed Rollie Fingers for the career saves record. The next season, Lee Smith passed Reardon.

Answer to #12 is Al Worthington with 5 straight seasons.1964-1968.

Worthington, who celebrated his 95th birthday last week, posted those seasons aged 35-39. For his career, Worthington recorded 8 seasons with 75+ IP in relief, including two (1957-58) in which he also logged 60+ IP as a starter.

#10: Jonathan Papelbon

You would certainly think Papelbon’s 517 ERA+ would have to be the best. But there’s another rookie season even better.

Finally found it: Rob Murphy in 1986.

#9: Pedro Martinez with five? Walter Johnson is the only other pitcher I have found with even three such seasons.

Pedro is correct. I think the totals are:

5 – Pedro

3 – Santana, Walter Johnson

2 – Vance, Seaver, Randy Johnson

1 – Waddell, Alexander, Grove, Newhouser, Koufax, Kershaw, Dutch Leonard, Hippo Vaughn, Harry Brecheen, Mike Scott

#6) Mo Vaughn 1996-98 (with a 152 OPS+ to boot)

Vaughn is correct.

Which contemporary of Vaughn bested his feat as a first baseman, with 5 such consecutive seasons including, like Vaughn, 150 OPS+ and 35+ HR each year?

Frank Thomas?

Thomas posted those seasons from 1993 to 1997, thus including two short seasons (one that was really short) in which he still managed to swat 35+ dingers.

Frank Thoams was doing a Ted Williams imitation for a while there. Interesting that both 1995 league MVP’s, Vaughn and Larkin, had better seasons in 1996 and didn’t get a single first place vote for MVP between them

Nothing against Vaughn. He had a fine season in ’95, but had no business beating out Thomas and, especially, Albert Belle for MVP.

Thomas was the 2-time defending MVP and, since his numbers were down from ’94 when he just plain unconscious, I can sort of see why voters would shy away from him. But, Belle? 103 XBH, 377 TB, only 50 double/50 HR season ever, and all in a short season, and he was even almost league average defensively (-1 Rfld). So, maybe he was a bit of a jerk, but is that a reason to jerk him around in the MVP vote! Hope not, but I suspect his personality certainly influenced more than a few voters.

In 1995, Jayson Stark (who’s actually a real nice guy and fan of the game) wrote sort of a “Nah-Nah” article about Albert’s “pretty numbers” and his failure to treat people (i.e. Sportswriters/The Voters) in a humane fashion and the apparent consequences.

Supposedly, Belle was very intelligent but was either on a steroid cycle or just had a loose screw…..”but, hey, I’m no doctor”. He had a few years putting up incredible numbers with the Tribe – and at least one with CWS as well

#5) Anthony Rizzo with six (?)

Not Rizzo.

How about Frank Robinson?

Not Robinson.

Hint is that the player you’re looking for was a contemporary of Willingham, playing against him in over 40 games. In those head-to-head tilts, Willingham had the edge over the career leader in HR, 2B and BB.

I was surprised that someone had more than Robinson’s seven. But Carlos Delgado had far more, with ten consecutive seasons.

Delgado is correct.

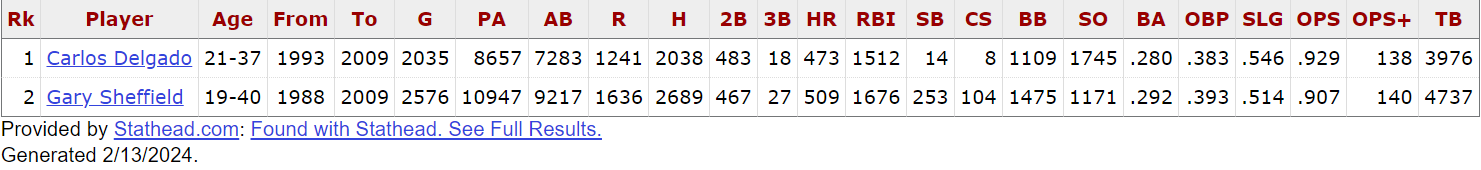

Certainly some similarities between Delgado and his 2009 Mets teammate Gary Sheffield. Both defensively challenged sluggers, they put up similar career rate stats and power numbers (stolen bases are a notable and significant difference in Sheffield’s favor):

They also had very similar peak WAR for 5 years (26.1/25.9, Delgado first) and 10 years (41.8/41.1). But, Sheffield logged about ⅓ more career WAR with about 25% more games, starting his career earlier and finishing later. Here are their PA and WAR:

Thru age 24 – Delgado: 823/0.4, Sheffield: 2419/7.6

Age 35+ – Delgado: 1405/2.1, Sheffield: 2912/11.8

Answer to #1: Manny Machado

Doug mentioned Adam Darowski’s Hall of Stats rankings in a great discussion thread on Johann Santana above, with arguments from Voomo and nsb. Adam (who posted here a few times, as I recall) evaluates players on the basis of a formula weighing peak measures against cumulative statistics, arriving at a single number, as Doug mentions. For context of scale, Ruth is at the top with 399. Six players break 300; 25 more break 200; 36 more break 150. Anyone with a score of 100 or more is in Adam’s “Hall of Stats” and has a ranking. There are 242 members. (The CoG is more exclusive, with 140 current members.)

Here are Adam’s ratings for all the players on the holdover ballot, plus Johann:

Wallace 146 (Rank: #76 all time)

Rolen 143

Utley 135

Tiant 128

Randolph 125

Lyons 124 (Rank: #141 all time — with 141 = the size of the CoG after this round)

Helton 121

Allen 116

Sheffield 116

Simmons 113

Guerrero 112

Minoso 111

Santana 108 (Rank: #200 all time)

Ortiz 95

Last round I voted for Wallace, Lyons, and Rolen, with the first two based on a concern that they would fall by the wayside because of distance in history, rather than merit, and Rolen based on WAR (although these three are indeed the top three in WAR on our list too). This time I’m going to add in reflection on Adam’s figures too before voting, along with thought of Doug’s very good discussion of Tiant last round.

And I’d urge every one to read nsb’s discussion of Santana (and Koufax, etc.) because of his very nuanced view of how it’s important not to ignore the contexts of the specific skills of these players and the eras they played in. It’s what makes CoG voting a complex pleasure–and difficult.

Bob:

One of the unfortunate results of baseball fandom turning blindly to interpretive statistics as the ultimate source of judgment—an awkward beginning, but let it stand—one of those results is that reasoned discussion and arguable disagreement are stifled. Don’t have to look at the details of a player’s career, don’t have to judge him critically, don’t need to know his biography or his teams’ histories during his playing career, don’t need even to know the difference among eras, dead ball, live ball, steroid, and all the others. Just need to know WAR.

Somewhere in the works of Thomas Wolfe there’s a vignette about an old crippled Confederate Civil War veteran who silences all discussion about the conflict by pointing to the site of his wound and saying “Look ye thar!” I’m not saying —or maybe I am—that Baseball Reference, FanGraphs, et al try to do the same thing concerning the vast intriguing, complicated subject of Baseball, but my impression is that because of their efforts to quantify overall performance into one number, far too many casual followers of the game have no interest in the specifics that used to fuel the reasoned discussion and arguable disagreement mentioned above.

In extra innings when the game was on the line Mickey Mantle batted .361 with an OPS of 1.305. Don Drysdale’s W/L percentage against teams that finished above .500 was .495. His teammate Sandy Koufax’s was .651. Ron Santo played his entire career without allowing it ever to be known that he suffered from diabetes. Hoyt Wilhelm’s knuckler resulted in at least 271 passed balls. Mariano Rivera’s battery mates allowed 14 in about 55% as many innings.

Each of these facts has meaning. Each bears upon how we assess or ought to assess the value of the players to which they are attached. They aren’t just trivia, factoids to amuse.

So—yes, more discussion, less quick judgment in the COG voting would be welcome.

Can you re-write that line about Mariano? I don’t understand..

I think nsb’s point is that, great as Wilhelm’s knuckler was, it had an enormous downside (so to speak) in terms of generating PBs that affected game outcomes, whereas Rivera’s cutter did not.

I remember that the Orioles provided Wilhelm’s catcher, Gus Triandos, with a hugely oversize mitt at one point. The goal wasn’t to catch the knuckler, just to block it.

Great stat on Drysdale vs. Koufax. Fans of Brooklyn–even once they started playing home games away–were well aware of this contrast.

Got it. It was a comparison to Wilhelm.

Voomo:

Wilhelm’s passed ball numbers, according to observers during his career (although admittedly, I have no source for this observation except my own aged memory) were understated, but even given the data as is, Rivera’s battery mates allowed a mere10.9 percent as many. I just picked Rivera for comparison because he’s regarded as the premier reliever of all-time by numerous informed observers. Gossage may be a better match. In 1800 innings he suffered 17 passed balls compared to 271 in 2250 for Wilhelm or 9.4 percent.

All three were relief pitchers (although Wilhelm and Gossage each spent one season as a starter).The point, of course is that relievers spend much of their time on the mound with runners on base. Their job is to prevent those runners from advancing. Passed balls allow runners to advance. Wilhelm’s percentage of inherited runners who scored was .35, Rivera’s .29, Gossage’s .33, Reardon .30, Hoffman .20, Smith .28.

Wilhelm recorded an abnormally high number of wild pitches too, probably owing to the knuckler. The knuckler took away, but it also gave.

Great comment. Couldn’t have said it better myself.

For the unanswered question 14 of the prior posting I came up with Gaylord Perry in game 1 of the 1971 NLCS as the Giants defeated the Pirates 5-4.

#3 above sounds an awful lot like Eddie Brinkman at 65 OPS+ (also, he had a 59 OPS+ TWICE with the Tigers in qualified seasons). But, just a guess, as I couldn’t recollect any hitters in Tigers’ history that bad…..

Brinkman is correct. His 65 career OPS+ is the lowest among all players with 5000+ PA careers who were ever selected to an All-Star team. That mark is lower even than Alfredo Griffin (67 OPS+) whose only All-Star appearance resulted from being plucked from the stands (literally) as an emergency replacement for Alan Trammell, who was injured in pre-game warmups for the 1984 game (Trammell didn’t return to the Tiger lineup until the end of July; they were still 13-5 without him, en route to their first pennant and WS title in 39 years).

#8) Bruce Hurst & Ed Whitson in 1989 , 1990.

Whitson led the NL in pitching WAR (7.0) in 1990 while going 14-9…. he was no match for Doug Drabek at 22-6 and garnered ZERO votes let alone any first-place votes

Hurst had a nice career, with 34 WAR and ten straight seasons with double-digit wins. Will always remember his 1986 World Series for which, if not for Buckner’s famous miscue, he might well have been named MVP, pitching 17 innings (the first 15 scoreless) to win games 1 and 5. Instead, he comes back on short rest in game 7 and stakes the Red Sox to a 3-0 lead after 5 innings. But, he was left in the game one inning too long, and the Mets completed their improbable comeback.

I’m sure you all know this but it’s amazing enough to bear repeating.

Hurst was the first left-handed Red Sox pitcher to win a world series game since Babe Ruth.

And an anagram of his name is:

B Ruth Curse

Never heard that one – Thanks!!

Vote:

Minnie Minoso

Willie Randolph

Johan Santana

Vote:

Secondary

Ashburn

Covlelski

Andruw Jones

Andruw Jones had an 11 year peak in which he averaged

157 Games

33 HR

100 RBI

5.5 WAR

22 rField

Arguably the greatest defensive CF ever.

For the 1979 – Part 3 election, I’m voting for:

-Vladimir Guerrero

-Todd Helton

-Willie Randolph

Other top candidates I considered highly (and/or will consider in future rounds):

-Rolen

-Utley

-Tiant

-Allen

-Wallace

-Lyons

-Sheffield

Quick Note: Should Brandon Webb have been listed as one of the new candidates for this selection? I would not be voting for him, but it looks like he had a 33.0 WAR.

Thanks!

You’re absolutely right, Opal. Brandon should be on the list. Sorry I missed him.

I’m guessing Webb would not have been the winner of the round but, since he arguably could have attracted a vote with that WAR total, I’ll keep him on the ballot for our next round.

For the Secondary Ballot, I’m voting for:

-Don Sutton

-Andre Dawson

-Andruw Jones

Thanks!

For reasons discussed above, I’m going to vote the Modified-Historical Party ticket:

Bobby Wallace

Ted Lyons

Luis Tiant

nsb has been calling for nuance in CoG decisions, and I’m going to be singlemindedly focused on nuance in presenting another iteration of The Case For Bobby Wallace.

1) My nuanced case for Wallace’s stats: Among eligible candidates he’s at the top of the WAR chart (76.4 — better than half the CoG membership) and the top candidate according to The Hall of Stats (see above).

2) My nuanced case for Wallace within his era: a pretty-good-pitcher-turned-virtuoso-shortstop (and above-average-batter), Wallace is the man who invented the modern shortstop scoop-and-throw, a highly nuanced motion. Wallace is the font of virtuoso shortstopism, whose image we see replicated in every routine 6-3 out.

3) My nuanced case for Wallace in history: He has (and I know this because I am making it up) the all-time highest Achievement/Recognition Ratio (ARR). This is a highly nuanced stat. Barney Dreyfuss said in 1911, “The best player in the American League, the only man I would get if I could, plays on a tail-end team, and few people pay any attention to him. I mean Bobby Wallace of St. Louis. I wish I had him.” At that time, Wallace’s ARR was already, as Dreyfuss clearly realized, an MLB-leading 54.6. But, as you know, lifetime ARR shifts even long after the lifetime ends, and Wallace’s ARR is now approaching 8-digit range, #1 on the B-R charts for players with more than 100 PA. There are of course, players with 50 or 60 PA whose ARR is infinite, because no one even remembers how to spell their names, if they actually had names (for example, Scott of the 1884 Baltimore Monumentals, whose last name is unknown, or whose first name is unknown, who hit a home run, and who some researchers believe was probably John Doe or his grandfather in witness protection).

Wallace has been spinning in the candidate circles of limbo or lower for years and years, his WAR steady, his ARR growing, and the time has come to lift him from those circles to the Great One, the CoG, where all nuance fades into the simple unity of The Elect. There may Wagner and Appling, Reese, Jeter, and Smith all scoop down in homage to the Paradigm of their Position and throw up their arms in welcome.

And also I’m stickin’ with Lyons, and Doug’s case for Luis last round earned him my vote.

Bob,

Quite nuanced, indeed.

I have to belive that “Scott” of the 1884 B’more Monumentals refers to a surname. The “Scott” moniker as a first name really has only caught hold in the last 60 years or so. Beam me up….

Paul, I’m sure you’ll recall that the 1871 Rockford Forest Cities were managed by the 24 year-old Scott Hastings, said to be the inventor of catcher hand signals. Hastings was still playing professionally as late as 1887 and could easily have been the Monumental Scott of 1884, especially if he’d shaved his prominent moustache in order to play in the Union Association incognito.

This is certainly a topic worthy of further research. Since Hastings’s first name was officially Winfield (the things we do to children!) I have to acknowledge a lapse in not considering the possibility that “Scott” was neither a first nor last name. (And had he been listed merely as “Winfield” I imagine many of us would have been egregiously misled.)

Interesting that Dreyfuss made the remark in 1911. As the Pirates owner, he presumably had not seen much of Wallace’s play since his NL days, which had ended ten years earlier. I suppose since his man Wagner was still going strong at 37, he assumed the same of Wallace, who was the same age.

Main Ballot;

Vladimir Guerrero

David Ortiz

Minnie Minoso

Secondary Ballot:

Bobby Abreu

Ken Boyer

I sort of forgot about this site for a while. I’m happy to see the COG is still going.

Main Ballot: Ortiz, Sheffield, Santana

Secondary: Sutton

Welcome back Chris.

On the subject of reducing everything to one statistic, here is a stat I created called PaWaa (Plate Appearances per Win Above Average).

It another way of looking at WAR,but Ive also broken it down in to PaWaa2000, PaWaa5000, PaWaa7000, PaWaa8000, PaWaa9000, PaWaa10000, and PaWaa11000…

…as a way of looking at players in the first xxxx# of PA in their career. This is to give perspective to careers like Albert Pujols, whose perceived greatness was diminished by longevity.

This list is probably not complete. And I just updated it for the first time since 2015, without going through Every one of the great players from this decade…

PaWaa – Career – Minimum 2000 PA

84.4 … (10622) Babe Ruth

97.2 … (9480) Rogers Hornsby

102.1 … (12606) Barry Bonds

102.5 … (6521) Mike Trout***

104.0 … (9788) Ted Williams

113.5 … (12496) Willie Mays

118.5 … (5404) Jose Ramirez***

122.2 … (3619) Aaron Judge***

124.0 … (5757) Mookie Betts***

123.1 … (9663) Lou Gehrig

125.7 … (9907) Mickey Mantle

127.7 … (11748) Honus Wagner

128.5 … (13084) Ty Cobb

135.8 … (11992) Tris Speaker

137.3 … (10062) Mike Schmidt

138.9 … (2084) Red Ruffing

140.5 … (7673) Joe DiMaggio

141.3 … (5695) Joe Jackson

147.3 … (5804) Jackie Robinson

150.7 … (13941) Hank Aaron

153.8 … (9676) Jimmie Foxx

155.8 … (12717) Stan Musial

160.7 … (11348) Melvin Ott

161.1 … (12207) Alex Rod

163.3 … (7722) Arky Vaughan

164.5 … (7370) Johnny Mize

164.8 … (6097) Hank Greenberg

166.4 … (7024) Lou Boudreau

166.6 … (8030) Larry Walker

172.4 … (10100) Eddie Mathews

176.2 … (6537) Joe Gordon

176.8 … (2033) Yordan***

179.3 … (11329) Joe Morgan

179.8 … (10211) Roberto Clemente

181.5 … (11742) Frank Robinson

182.1 … (9431) Jeff Bagwell

186.5 … (8674) Johnny Bench

187.5 … (3375) Juan Soto***

188.4 … (10740) Wade Boggs

189.4 … (8220) Bobby Grich

190.0 … (6443) Nolan Arenado***

192.2 … (7863) Chase Utley

194.5 … (13346) Rickey Henderson

209.7 … (11596) Al Kaline

212.1 … (6874) Manny Machado***

214.6 … (9057) Barry Larkin

215.9 … (13041) Albert Pujols

216.9 … (7745) Mike Piazza

223.6 … (7065) Bill Dickey

225.9 … (8674) Edgar Martinez

226.6 … (9019) Gary Carter

229.3 … (10550) Rod Carew

230.7 … (11625) George Brett

232.7 … (8237) Duke Snider

233.2 … (9376) Alan Trammell

234.5 … (9967) Lou Whitaker

241.8 … (9235) Kenny Lofton

242.6 … (12883) Cal Ripken

243.1 … (11304) Ken Griffey

243.6 … (9282) Ryne Sandberg

246.3 … (8840) Joe Cronin

247.1 … (10254) Luke Appling

247.2 … (6454) Bryce Harper***

247.3 … (8359) Yogi Berra

256.0 … (9397) Ron Santo

257.0 … (10075) Frank Thomas

259.1 … (10778) Ozzie Smith

262.9 … (8098) Fred Freeman***

280.4 … (13992) Carl Yaz

280.7 … (9853) Carlton Fisk

281.1 … (10232) Tony Gwynn

287.8 … (7712) Minnie Minoso

289.8 … (8143) Joe Medwick

296.0 … (10359) Tim Raines

297.5 … (11782) Brooks Robinson

298.7 … (9470) Pee Wee Reese

306.7 … (4815) Roy Campanella

318.8 … (9692) Willie McCovey

322.0 …(10400) Roberto Alomar

324.4 … (11418) Reggie Jackson

328.0 … (12167) Paul Molitor

331.0 … (12249) Robin Yount

350.0 … (9833) Harmon Killebrew

364.7 … (10394) Ernie Banks

413.2 … (12602) Derek Jeter

435.7 … (12504) Craig Biggio

474.8 …(12817) Eddie Murray

521.4 …(12358) Dave! Winfield

555.6 … (15890) Pete Rose

PaWaa 2000

74.3 … Babe Ruth

104.5 … Mike Trout

105.9 … Joe Jackson

109.1 … Stan Musial

111.6 … Ted Williams

113.2 … Willie McCovey

116.2 … Rogers Hornsby

113.7 … Willie Mays

127.3 … Kenny Lofton

127.6 … Lou Gehrig

133.4 … Red Ruffing

135.4 … Aaron Judge

135.6 … Bobby Grich

136.1 … Cal Ripken

137.0 … Johnny Mize

137.4 … Mookie

137.5 … Mike Schmidt

139.5 … Albert Pujols

142.5 … Mike Piazza

143.4 … Wade Boggs

146.5 … Alex Rod

147.5 … Jimmie Foxx

154.4 … Chase Utley

155.5 … Carlton Fisk (took him 7 years)

157.1 … Tris Speaker

158.7 … Rickey Henderson

159.5 … Frank Thomas

164.0 … Arky Vaughan

164.3 … Mickey Mantle

164.4 … Eddie Mathews

171.3 … Joe DiMaggio

173.7 … Johnny Bench

176.8 … Yordan

178.0 … Barry Bonds

178.3 … Edgar Martinez

178.9 … Juan Soto

179.5 … Mel Ott

183.3 … Craig Biggio

186.4 … Willie McCovey

188.4 … Manny Machado

189.1 … Frank Robinson

189.4 … Hank Greenberg

192.0 … Ken Griffey

199.3 … Jackie Robinson

200.5 … Joe Gordon

202.0 … Al Kaline

206.5 … Reggie Jackson

210.9 … Ty Cobb

210.9 … Barry Larkin

212.9 … Nolan Arenado

214.2 … Ernie Banks

215.1 … Honus Wagner

219.8 … Jeff Bagwell

233.1 … Gary Carter

235.6 … Larry Walker

237.3 … Jose Ramirez

238.2 … Hank Aaron

239.1 … Tony Gwynn

241.1 … George Brett

249.9 … Lou Boudreau

252.0 … Ryne Sandberg

255.6 … Derek Jeter

258.9 … Joe Morgan

288.7 … Rod Carew

289.4 … Paul Molitor

291.7 … Yogi Berra

292.2 … Tim Raines

300.6 … Lou Whitaker

365.9 … Duke Snider

433.6 … Pee Wee Reese

451.1 … Carl Yaz

508.6 … Alan Trammell

614.8 … Ozzie Smith

1117.2 . Pete Rose

3368 . Brooks Robinson

Negative … Roberto Clemente

Negative … Ron Santo

Negative … Robin Yount

PaWaa 5000

77.6 … Babe Ruth

93.8 … Ted Williams

96.0 … Mike Trout

97.9 … Rogers Hornsby

103.0 … Mickey Mantle

108.5 … Ty Cobb

109.8 … Willie Mays

111.8 … Barry Bonds

116.5 … Stan Musial

116.8 … Albert Pujols

117.6 … Lou Gehrig

118.5 … Jose Ramirez

118.7 … Tris Speaker

120.8 … Jimmie Foxx

121.1 … Mike Schmidt

121.8 … Wade Boggs

126.1 … Honus Wagner

128.0 … Ken Griffey

128.8 … Alex Rod

129.8 … Chase Utley

130.9 … Joe DiMaggio

133.7 … Johnny Mize

136.4 … Rickey Henderson

138.1 … Arky Vaughan

140.8 … Jackie Robinson

141.0 … George Brett

142.5 … Hank Aaron

143.8 … Joe Jackson

147.1 … Mike Piazza

148.3 … Ernie Banks

148.3 … Jeff Bagwell

148.9 … Eddie Mathews

154.6 … Mel Ott

155.5 … Frank Thomas

157.4 … Bobby Grich

158.4 … Johnny Bench

159.5 … Gary Carter

159.7 … Kenny Lofton

160.5 … Frank Robinson

161.8 … Hank Greenberg

162.8 … Lou Boudreau

164.8 … Reggie Jackson

165.2 … Joe Gordon

168.9 … Carl Yaz

169.4 … Larry Walker

172.7 … Barry Larkin

174.8 … Al Kaline

176.7 … Duke Snider

176.8 … Cal Ripken

178.3 … Edgar Martinez

184.0 … Carlton Fisk

186.4 … Willie McCovey

188.1 … Nolan Arenado

189.2 … Joe Morgan

195.4 … Tim Raines

196.3 … Rod Carew

197.0 … Ron Santo

210.1 … Willie McCovey

210.5 … Manny Machado

221.7 … Yogi Berra

240.8 … Lou Whitaker

243.0 … Derek Jeter

243.2 … Tony Gwynn

252.7 … Alan Trammell

255.4 … Pee Wee Reese

256.0 … Paul Molitor

262.9 … Robin Yount

266.9 … Craig Biggio

298.5 … Ryne Sandberg

324.0 … Ozzie Smith

333.3 … Brooks Robinson

349.2 … Pete Rose

468.8 … Roberto Clemente

PaWaa 7000

77.1 … Babe Ruth

94.0 … Rogers Hornsby

97.0 … Ted Williams

102.5 … Mike Trout

104.2 … Ty Cobb

105.6 … Mickey Mantle

106.8 … Willie Mays

107.9 … Honus Wagner

108.1 … Barry Bonds

111.2 … Albert Pujols

117.1 … Stan Musial

117.3 … Lou Gehrig

117.6 … Mike Schmidt

124.5 … Rickey Henderson

125.3 … Tris Speaker

125.4 … Alex Rod

135.2 … Joe DiMaggio

135.3 … Jimmie Foxx

135.4 … Hank Aaron

136.4 … Wade Boggs

139.6 … Joe Morgan

142.4 … Ken Griffey

143.4 … Mel Ott

145.7 … George Brett

150.6 … Eddie Mathews

151.9 … Cal Ripken

153.5 … Arky Vaughan

155.3 … Jeff Bagwell

157.8 … Johnny Mize

157.9 … Frank Robinson

160.0 … Larry Walker

160.8 … Gary Carter

161.3 … Johnny Bench

165.3 … Barry Larkin

166.0 … Lou Boudreau

166.3 … Bobby Grich

168.9 … Carl Yaz

174.9 … Rod Carew

177.8 … Al Kaline

179.5 … Reggie Jackson

185.3 … Edgar Martinez

193.2 … Frank Thomas

197.3 … Duke Snider

198.8 … Mike Piazza

199.6 … Kenny Lofton

203.0 … Ron Santo

203.6 … Ernie Banks

208.9 … Alan Trammell

210.1 … Willie McCovey

214.3 … Craig Biggio

217.2 … Carlton Fisk

220.7 … Yogi Berra

227.8 … Ryne Sandberg

231.5 … Tony Gwynn

233.6 … Tim Raines

236.2 … Eddie Murray

237.4 … Minnie Minoso

240.9 … Joe Cronin

244.0 … Brooks Robinson

245.6 … Robin Yount

246.1 … Paul Molitor

248.0 … Lou Whitaker

254.4 … Harmon Killebrew

254.6 … Pee Wee Reese

255.1 … Ozzie Smith

264.5 … Joe Medwick

271.5 … Roberto Clemente

274.4 … Derek Jeter

287.0 … Roberto Alomar

288.6 … Dave Winfield

295.6 … Luke Appling

302.4 … Pete Rose

PaWaa 8000

79.1 … Babe Ruth

93.7 … Rogers Hornsby

96.1 … Ted Wiliams

101.5 … Willie Mays

103.9 … Ty Cobb

108.6 … Mickey Mantle

109.2 … Barry Bonds

109.2 … Honus Wagner

115.4 … Lou Gehrig

121.0 … Stan Musial

121.5 … Albert Pujols

123.4 … Mike Schmidt

124.7 … Tris Speaker

128.7 … Rickey Henderson

132.4 … Alex Rod

133.4 … Jimmie Foxx

133.8 … Hank Aaron

141.7 … Joe Morgan

142.5 … Mel Ott

148.3 … Eddie Mathews

155.0 … Wade Boggs

156.3 … George Brett

157.2 … Ken Griffey

161.6 … Cal Ripken

161.9 … Frank Robinson

164.3 … Johnny Bench

164.8 … Jeff Bagwell

166.6 … Larry Walker

175.4 … Barry Larkin

175.9 … Al Kaline

178.4 … Carl Yaz

184.4 … Bobby Grich

187.7 … Reggie Jackson

190.7 … Rod Carew

197.9 … Gary Carter

199.6 … Edgar Martinez

201.9 … Alan Trammell

212.3 … Kenny Lofton

213.0 … Roberto Clemente

213.3 … Ryne Sandberg

216.2 … Ron Santo

219.3 … Duke Snider

219.6 … Frank Thomas

224.1 … Willie McCovey

225.3 … Tim Raines

231.1 … Craig Biggio

232.9 … Lou Whitaker

233.0 … Yogi Berra

240.1 … Ozzie Smith

241.1 … Tony Gwynn

245.5 … Luke Appling

246.6 … Paul Molitor

246.8 … Joe Cronin

250.5 … Eddie Murray

251.2 … Pee Wee Reese

251.5 … Brooks Robinson

257.1 … Roberto Alomar

257.2 … Robin Yount

257.6 … Ernie Banks

264.0 … Carlton Fisk

264.8 … Pete Rose

268.7 … Derek Jeter

270.8 … Harmon Killebrew

282.1 … Joe Medwick

314.6 … Dave Winfield

PaWaa 9000

79.4 … Babe Ruth

94.9 … Rogers Hornsby

97.0 … Ted Williams

98.3 … Willie Mays

109.2 … Honus Wagner

110.3 … Ty Cobb

110.7 … Barry Bonds

115.7 … Mickey Mantle

116.4 … Lou Gehrig

123.4 … Tris Speaker

123.9 … Stan Musial

126.1 … Mike Schmidt

128.9 … Alex Rod

131.2 … Hank Aaron

132.0 … Rickey Henderson

134.5 … Albert Pujols

140.6 … Jimmie Foxx

151.5 … Mel Ott

156.0 … Eddie Mathews

157.7 … Wade Boggs

158.0 … Frank Robinson

158.8 … Joe Morgan

170.0 … George Brett

171.5 … Ken Griffey

173.9 … Cal Ripken

173.9 … Al Kaline

179.7 … Jeff Bagwell

187.6 … Carl Yaz

192.6 … Roberto Clemente

195.9 … Rod Carew

207.0 … Reggie Jackson

212.7 … Alan Trammell

214.6 … Barry Larkin

225.6 … Ron Santo

226.6 … Gary Carter

227.4 … Ryne Sandberg

229.1 … Frank Thomas

230.1 … Lou Whitaker

232.5 … Ozzie Smith

241.4 … Roberto Alomar

241.8 … Luke Appling

241.8 … Kenny Lofton

247.8 … Paul Molitor

250.8 … Carlton Fisk

252.2 … Tony Gwynn

252.9 … Brooks Robinson

253.6 … Willie McCovey

255.9 … Tim Raines

263.3 … Robin Yount

266.3 … Pete Rose

268.4 … Eddie Murray

269.2 … Pee Wee Reese

272.8 … Craig Biggio

275.1 … Ernie Banks

293.0 … Harmon Killebrew

294.3 … Derek Jeter

342.4 … Dave Winfield

PaWaa 10,000

82.0 … Babe Ruth

101.6 … Willie Mays

106.0 … Barry Bonds

112.4 … Honus Wagner

112.7 … Ty Cobb

115.7 … Mickey Mantle (9907)

125.5 … Tris Speaker

129.3 … Stan Musial

132.4 … Hank Aaron

136.6 … Alex Rod

137.3 … Mike Schmidt

137.9 … Rickey Henderson

156.5 … Mel Ott

165.3 … Frank Robinson

168.4 … Joe Morgan

169.0 … Wade Boggs

171.4 … Eddie Mathews

174.7 … George Brett

180.2 … Al Kaline

183.8 … Roberto Clemente

187.8 … Cal Ripken

198.2 … Carl Yaz

202.9 … Ken Griffey

213.0 … Rod Carew

234.5 … Lou Whitaker (9967)

239.8 … Ozzie Smith

241.3 … Luke Appling

253.2 … Pete Rose

257.0 … Frank Thomas

257.9 … Robin Yount

261.2 … Brooks Robinson

264.2 … Reggie Jackson

269.1 … Paul Molitor

275.7 … Tony Gwynn

279.5 … Derek Jeter

280.7 … Carlton Fisk (9853)

281.7 … Tim Raines

288.8 … Craig Biggio

294.1 … Eddie Murray

303.9 … Roberto Alomar

329.7 … Ernie Banks

357.3 … Dave Winfield

PaWaa 11,000

99.8 … Barry Bonds

106.0 … Willie Mays

119.7 … Honus Wagner

120.1 … Ty Cobb

128.3 … Tris Speaker

133.2 … Hank Aaron

140.1 … Stan Musial

144.0 … Alex Rod

153.6 … Rickey Henderson

155.3 … Mel Ott

172.9 … Joe Morgan

173.0 … Frank Robinson

193.7 … Al Kaline

202.5 … Cal Ripken

208.5 … Carl Yaz

208.6 … George Brett

234.7 … Ken Griffey

264.7 … Brooks Robinson

267.0 … Pete Rose

278.1 … Paul Molitor

297.0 … Robin Yount

300.9 … Reggie Jackson

317.2 … Craig Biggio

332.0 … Derek Jeter

345.3 … Eddie Murray

402.3 … Dave Winfield

PaWaa 12,000

99.8 … Barry Bonds

108.6 … Willie Mays

122.3 … Ty Cobb

134.7 … Hank Aaron

135.8 … Tris Speaker (11992)

147.7 … Stan Musial

170.0 … Rickey Henderson

217.1 … Cal Ripken

230.3 … Carl Yaz

288.3 … Pete Rose

328.0 … Paul Molitor

331.0 … Robin Yount

368.8 … Craig Biggio

369.4 … Derek Jeter

385.7 … Eddie Murray

454.2 … Dave Winfield

PaWaa 13,000

128.5 … Ty Cobb

137.8 … Hank Aaron

189.0 … Rickey Henderson

251.6 … Carl Yaz

327.5 … Pete Rose

PaWaa 14,000

150.7 … Hank Aaron (13941)

280.4 … Carl Yaz (13992)

391.7 … Pete Rose

PaWaa 15,000

478.3 … Pete Rose

Voomo:

A Herculean accomplishment. And the result shows players from all eras sprinkled through the ascending ratings.

If you tried this with pitchers, it would not be so. Owing to the current trend of pulling starters in the sixth inning more or less, the figures skew in their favor dramatically, at least in a simpler formation of pWAR/ IP. Dead ball era pitchers also have an advantage.

In other words, your version for position players is useful as a means to evaluate players across eras, but I think that if you would apply it to pitchers, you would find that dead ball and recent pitchers hold most of the top positions.

This brings me to the point: WAR was originally designed, I think, for batting stats. The pitching and fielding applications came later, and instead of developing new ways of looking at entirely different sets of raw stats that would account for cross-era shifts, the developers adapted the formulas they had.

Bob Eno, will probably disagree.

Of course I disagree! . . . But I need a while to figure out some basis for it. I just hope the reason you expected me to wasn’t because of my comic distortion of your term “nuance” to try to spice up repeating my same old arguments for Bobbly Wallace. We should absolutely go beyond single-stat reductions and look at complexes of skills and contexts. I wasn’t making fun of you, I was making fun of how much I’ve been repeating myself (and to such little effect!).

I was once on top of what WAR crunched but those days are long gone. It seems to me that the specific adaptation to pitching was justified by assessment of the weights given to its various components together with the empirical fact that the pitching/position player numbers lined up pretty well intuitively. But pWAR and bWAR are different things, and we used to make that distinction in CoG discussions–we’d routinely look at separate lists for position players and pitchers when the WAR figures were listed. (When I put Wallace on those lists, I always extracted his pitching years and added an asterisk.)

Within traditional roles, I don’t think there’s really anything that undermines WAR when it comes to cross-era comparisons because all the components are relative to the individual seasons in which they were compiled. WAR measures relative to the context of the season for all seasons, so I can argue that Bobby Wallace is better than Willie Randolph, even though Randolph would objectively make Wallace look like a high schooler if both were 25 today.

But the specific point you make about six-inning starters belongs to a different category–the one that makes WAR so unsuited to relief pitchers. The quantity element of the WAR components does depend on having a common general expectation, and while the PA/bWAR may work for position players, the IP/pWAR/ doesn’t work because of the intensity of pitching and exaggerated effects of ordinary fatigue. Within a single season, this is why pWAR can’t cross the starter/reliever divide, and I think you’re right that it will present a distorted view across eras because starters will have much lower quantity within components and will have elevated quality factors because the parameters of fatigue have changed.

I’m not sure, however, that deadball era starters actually have an advantage in pWAR. I’d want to check it out. As a quick test I did a Matty/Maddux comparison, and found that Mathewson and Maddux–two pitchers who seem fairly comparable, but in radically different eras–have identical IP/pWAR: 5.31. (Snell, btw, comes in very close at 5.22.)

Bob:

Your screed on Wallace had nothing to do with my closing remark. We’d sparred about WAR applications in the long ago past, so I took a preemptive shot, rather than waiting.

PART ONE

Ed Lopat versus Johan Santana: Both were successful playing for good teams. Lopat was successful playing for some bad White Sox teams before going to the Yanks, and Santana was successful for some bad Mets teams after leaving the Twins.

IP 2439—2025

W 166—139

L 112-78

ERA 3.21—3.20

ERA+ 116—136

GS 318—284

CG 164—15

H/9 9.1—7.7

HR/9 0.7—1.0

SO% 8.4—24.1

BB% 6.4—6.9

pWAR/ IP: .0116—.0251

Question: Santana was better, true, but if he was more than twice as good, why doesn’t his W/L record show it? Or could it be that throwing complete games using junkballs and letting the fielders have a little say works well too? If so, then the ideal 81-pitch, 27 strikeout game may not be the only option. What about the 27-pitch, twenty-seven putout game as an alternative ideal?

PART TWO

Here are all the 2000+ IP starters I could find who spent the majority of the careers pitching in the 1950s. I may have overlooked one or two. The figure after each name is pWAR/innings pitched.

R. Roberts .0177

W. Spahn .0176

W. Ford .0169

B. Pierce .0162

N. Garver .0157

J. Antonelli .0157 (1992 IP)

M. Dickson .0152

M. Garcia .0141

F. Lary .0136

H. Haddix .0134

D Newcombe .0134

B.Lemon .0132

B. Friend .0130

C. Simmons .0128

E Wynn .0113

V. Law .0098

L. Burdette .0083

For contrast, here is a list of starters, basically from the 1990s through 2023, some still active, almost all with 2000+ innings. Again, the figure after each name is pWAR/ innings pitched.

Verlander .0245

Kershaw .0284

Scherzer .0265

Greinke .0214

Degrom .0310 (1356 IP and probably not many more, I suspect.)

Hamels .0215

Halladay .0238

Santana .0251

Clemens .0282

Maddox .0209

R. Johnson .0250

P. Martinez .0305

Mussina .0232

Schilling .0247

Brown .0209

Pettitte .0183

Glavine .0167

Moyer .0123

What bunch of losers those earlier guys must have been.

A continuation of the above:

PART THREE

Dead ball circa 1890-1919

C. Young .0225

K. Nichols .0229

C. Mathewson .0209

E. Plank .0195

R. Waddell .0206

J. Mcginnity .0180

A. Joss .0205

M. Brown .0180

E. Walsh .0215

W. Johnson .0258

G. Alexander .0224 (Half dead ball, half live ball)

Live ball circa 1920-1950 notables

U. Shocker .0205

D. Vance .0212

L. Grove .0287

D. Dean .0223 (1967 IP)

H. Brecheen .0217 (1907 IP)

C. Hubbell .0192

H. Newhouser .0201

R Faber .0156

T. Lyons .0161

L. Gomez .0173

B. Feller .0170

R. Ruffing .0127

W. Ferrell .0186

W. Hoyt ,0144

T Bridges .0183

B. Newsom ,0136

M. Harder .0142

B. Grimes .0112

B. Shawkey .0159

H. Pennock .0125

D. Luque .0136

C. Passeau .0160

B. Walters .0150

D. Trout ,0166

M. Cooper .0173 (1841 IP)

F. Fitzsimmons .0104

L. Warneke .0151

Remarks: Shocker, Dean, and Brecheen had short careers, Brecheen’s and Newhouser’s figures are boosted by WWII. Lefty Grove and Dazzy Vance are the only enduring pitchers of the era who best the .0200 mark, and Vance was something of an anomaly.

PART FOUR

The 1960s through the 1980s produced far too many pitchers with 2000+ innings to list them all here, so you’ll have to trust my judgment about inclusions and exclusions. No one who has a really high WAR/ IP rating will be left omitted. There are so few.

Seaver .0222

Koufax .0228

Gibson .0210

Blyleven .0199

Stieb .0195

Reuschel .0192

Jenkins .0183

Tiant .0188

P. Niekro .0179

Drysdale .0178

Marichal .0176

G. Perry .0174

McDowell .0173

Palmer .0171

Gooden .0171

Viola .0166

Carlton .0161

L. Jackson .0161

Bunning .0160

Ryan .0155

Koosman .0148

Pappas .0145

Tanana .0136

John .0135

Blue .0134

Lolich .0132

Sutton .0129

Pascual .0128

Valenzuela .0127

J. Perry .0117

Morris .0114

Hunter .0107

Osteen .0106

Kaat .0100

Reuss .0089

J. Niekro .0080

TO SUM UP

Pitchers with over .0200 WAR/IP:

8 Dead Ball Era plus Alexander

6 Live Ball Era through 1950s

3 Live Ball Era 1960s through 1980s

15 1990s to date

Too much work. Does anyone care? Only if you want to put a big question mark against the credibility of pitching WAR’s ability to compare eras.

Anyway, I’m done. Rip this if you will. I won’t reply.

No rip! This is great work, nsb.

Here’s a first reaction: It appears from this analysis that the reason starter pWAR is distributed unevenly across eras may be, in part, because of shifts in the distribution of activity on the diamond. That is, in certain eras, because of the style of play, pitchers shoulder more of the work, and thus FIP grabs a larger share of the statistical credit.

You essentially made this point in your Lopat/Santana contrast (what a well chosen match-up!). When Lopat spreads the work among fielders it may yield the same number of wins, but the fielders are gobbling up WAR with each play. Santana is keeping it all on his plate.

So I think your argument does indeed effectively challenge mine that pWAR is relative to season contexts and so can be fairly compared between eras. You get the win!

But . . . (of course) . . .there’s a tension in that unfairness too. The 81-strike perfect pitcher exercises near-complete control over the action on the field, while the 27-pitch perfect pitcher surrenders control to both the fielders and to the batters’ batted balls. It’s also fair to have the pWAR follow skill-exercised control.

Here’s another way to look at it. It seems to me that (excluding career-end seasons) Lopat was pretty regularly about .050 ahead of his teams in W-L Pct.–his W-L was mediocre when his ChiSox teams were bad and were good with the Yankees. Santana was well over .100 ahead of his teams when they were mediocre or good. We don’t give much weight to W-L anymore, but I think you can see here the difference in credit when a good pitcher takes on more control.

I’ll look for more time to pursue this further–you’ve crunched more than a century of stats to explore–but, as always, your point and your evidence are very good.

Using Voomo’s formula for the position players on the current ballot, this is what I get:

192.2 Utley (7839)

193.6 Rolen (8518)

222.3 Allen (7315)

262.1 Randolph (9461)

272.5 Minoso (7712 – MLB only; 290.9 [8232] total)

275.2 Wallace (9631)

283.9 Helton (9453)

307.1 Guerrero (9059)

421.0 Sheffield (10947)

499.6 Ortiz (10091)

509.7 Simmons (9685)

I also tried to level the playing field and ran the figures using Utley’s PA total as a base. I looked for the season cutoff closest to 7839 PA and calculated the number:

180.0 Rolen (7919)

192.2 Utley [7839]

216.9 Helton (7764)

222.3 Allen [7315]

225.4 Wallace (7799)

244.6 Guerrero (7826)

250.3 Randolph (7534)

272.5 Minoso [7712]

302.6 Simmons (7444)

333.4 Sheffield (8035)

525.4 Ortiz (8249)

(Sheffield and Ortiz’s figures improved by choosing the higher of two PA figures.)

Question #11: Not sure if he is first, but one of the three pitchers ahead of Rodríguez is Camilo Pascual, whose ERA+ improved 48 points from his first three seasons to his next three (72 to 120).

Not Pascual. Someone much more recent.

Hint is he logged a bit more than half of Pascual’s innings and earned a bit more than half of Pascual’s WAR. Their career IP to WAR ratios are within 2% of each other.

Another pitcher ahead of Rodriguez, but not first, is Bill Swift who went from 86 to 132 for 46 points of improvement.

I had considered this pitcher previously but apparently neglected to check his numbers: Jake Arrieta improved dramatically upon joining the Cubs once the Orioles traded him after 3-1/2 seasons. His ERA+ went from 79 in seasons 1-3 to 152 over the next three campaigns.

Arrieta is correct. His 12-year career broken down into 3 year chunks looks like this:

Year 1-3, 79 ERA+

4-6, 152

7-9, 120

10-12, 77

So, a 30+ point change in ERA+ each time. Likely very few (if any) similar careers.

My vote:

Main: Utley, Tiant, Wallace

Secondary: Ashburn, Dawson, Jones

I was surprised by how high Utley was ranked in Hall of Stats so, since he is on the bubble, will give him some support.

On the secondary, I’ve chosen three excellent centerfielders, two with a career value case, and one based more on peak value. Possibly one of the three belongs in the CoG.

As it stands now, there are 7 players tied for the lead, but with only two votes. Rather than a 7-way runoff, I’m going to extend the election for another week in the hope that we will get a few more voters to weigh in.

Previously cast ballots may now be changed up until this coming Friday. Note also the addition of Brandon Webb to the ballot, whom I had missed in preparing the post. Thanks to Opal for pointing out this omission.

Doug, as the site admin, do you have access to all the emails of folks who have voted over the years?

And if so, it it in integrity to message everybody that we are having an active vote? We dont have a “subscription” option on this site.

I have some Admin rights. but Andy is the ultimate site admin.

I do have access to comments, over 80,000 of them going back to 2012. But no easy way to extract them to strip off the e-mail addresses.

But, I’ll see what I can do.

Wow. Say hi to Andy! It’s been a long time.

Main: Allen, Rolen, Simmons

Secondary: Williams, Coveleski, Reggie Smith

Since we’ve got some extra time, I thought I’d do a version of something I used to do back in the day and list all of our candidates—on both lists—according to a formulation that’s a little different from usual. In this case, for position players, the candidates are listed according to PA/WAR (productivity)—lower numbers better, as in Voomo’s PA/WAA—and their career magnitude, expressed as “Irvins”—that is, their total PAs expressed as a multiple of Monte Irvin’s total PAs, the lowest magnitude on the list (this includes all of his PAs, including his ten Negro League seasons, but because the Negro League stats are very incomplete, those ten years comprise less than 30% of his total PAs).

Here’s the position player list:

PA/WAR…Irvins

110………1.0…Irvin*

121………2.4…Rolen

122………2.2…Utley

125………2.1…Allen

125………2.3…Smith*

132………2.3…Boyer*

133………2.0…Minoso

133………2.7…Wallace

138………2.5…Jones*

144………2.7…Randolph

151………2.8…Ashburn*

153………2.6…Guerrero

153………2.7…Helton

165………3.0…Williams*

166………3.1…Dawson*

167………2.9…Abreu*

181………3.1…Sheffield

182………2.9…Ortiz

193………2.7…Simmons

The asterisks are for Secondary Ballot candidates. I think it’s interesting that there’s really no clear division between members of the two ballots. That goes for straight WAR too. If you set aside Irvin, whose stats are very incomplete so his WAR is artificially low, then the lowest-WAR Secondary candidate (Abreu) has a higher WAR total than five of the primary ballot candidates (in descending order, Guerrero, Allen, Ortiz, Minoso, and Simmons), with Sheff just edging Abreu out. And on the Primary ballot, only three candidates top Drysdale’s WAR: Wallace, Lyons, and Rolen.

Note that Minoso, like Irvin, has Negro League seasons (three, in his case), plus a break as he moved into MLB that took productivity away during his peak period, so, like Irvin, he’s working with a handicap, but still doing ok. For Wallace, I need to note that I removed the PAs for his three pitching years, since we don’t measure pitcher careers in PAs (those years show up below), which works in Wallace’s favor, but I retained his bWAR for those seasons, which was -1.2, which works against him. Wallace also appears with the pitchers below.

Here are the pitchers, with career magnitude expressed in terms of Johans.

IP/WAR…Johans

39………1.0…Santana (newly eligible)

50………1.5…Coveleski*

51………1.7…Drysdale*

53………1.7…Tiant

59………2.1…Lyons

67………0.2…Wallace

79………2.6…Sutton*

You can really see the trade-off between career magnitude and productivity with Johan, and the contrast with Sutton is particularly stark. It’s pretty striking to me that Wallace, who was ordinary enough to be moved to the field, looks ok next to Sutton, who’s in the Hall. If you threw in Wallace’s pWAR with his bWAR and added back in the PAs for his three pitching years, his career length would still be 2.7 Irvins, but his productivity would improve from 133 to 126. (I am, of course, always shilling for Wallace! His productivity/magnitude figures seem to stand out if you look at his total figures.)

I think the most noteworthy thing about looking at candidates this way is how arbitrary our Primary/Secondary ballot distinctions appear. This where we might want to take up nsb’s theme of nuance. Can we state clearly why it would be that, say, we have Drysdale on the secondary list and Tiant on the primary? Or, more obviously, why we have Sheffield, Ortiz, and Simmons on the primary ballot while Irvin, Smith, and Boyer are not—Smith, in fact, is tipping towards oblivion. There must be reasons beyond the stats, and if we could state them, we could assess whether or not they’re valid.

With this in mind, I’m going to cast a Secondary Ballot vote:

Irvin, Jones, Smith

Just to augment your pitcher list to include Brandon Webb, nearly as efficient as Johnan in WAR production.

39………1.0…Santana (newly eligible)

42……..0.7…Webb (newly eligible)

50………1.5…Coveleski*

51………1.7…Drysdale*

53………1.7…Tiant

59………2.1…Lyons

67………0.2…Wallace

79………2.6…Sutton*

Webb accumulated all of his positive WAR through his age 29 season (and all of his WAR, period, before his 30th birthday). He and Santana are two of only 10 modern era pitchers with IP per WAR as low as Webb’s in 1000+ IP through their age 29 seasons.

30…..Pedro

32…..Clemens

33…..Kershaw

35…..Sale

35…..Walter Johnson

36…..Santana

37…..Appier

37…..Seaver

38…..Oswalt

40…..Webb

Seaver and, especially, Johnson stand out as pitchers with low IP per WAR ratios, despite pitching longer into games than the rest of the pitchers on the list.

FWIW, Bill Foster checks in just behind Pedro, with 31 IP per WAR. Foster compiled 39.2 WAR in 1234 IP over ten Negro League seasons (1923-33), completing 108 of his 136 starts.

Thanks, Doug. Didn’t think to add him.

The super-efficient pitchers are top relievers:

23……..0.6…Mariano

33……..0.4…Wagner (not Honus)

One more chance for Wagner with the BBWAA, after two ballots north of 65%, including an ever so close 73.8% this year.

Only two “modern” relievers (i.e. primarily 9th inning only relievers, so careers since ~1990) in the Hall, so Hoffman is obviously the minimum Hall benchmark. He and Wagner had virtually the same WAR, but Hoffman logged 20% more IP and 42% more saves, so definitely has prettier numbers. Still, seems like there ought to be a place for a left-handed closer, who could put up comparable numbers to the best righties, despite a more challenging platoon environment.

While I have some time, I’m going to point out something that Bob Eno, for all his enthusiasm about Bobby Wallace, has somehow not exactly downplayed, but mentioned only in passing. Wallace was a darn good hitter for his era. His 56.8 Batting WAR in the dead ball era is a commendable in ways we may not really grasp now, or not easily. He was anything but a power hitter, and was middling at best at working the pitcher for a walk. Nevertheless he had 6 top-10 finishes in the offensive WAR category and 8 top-10 finishes in RBIs. Hitting in the clutch has been downplayed by the statistical wizards, and RBIs belittled as a function of batting order position, but I at least am still impressed by the fact that he led his own teams in RBIs nine times in an era, at least after 1901, when runs didn’t grow on trees like bananas.

He produced runs when they were scarce, he prevented runs to make them scarcer for his team’s opponents, and he did these things laboring in obscurity for the better part of his career.

He may not stand head and shoulders above the other candidates on this particular ballot, but he’s at least a couple of inches taller. That’s a metaphor, guys.

To your point, for the 16 years he played regularly (1897-1912), Wallace ranked 4th in oWAR, 3rd in WAR and 2nd in dWAR. So, not just a defensive wizard. Here’s the list.

I generally don’t vote, preferring to be a commentator, although I did vote once in order to break a senseless impending tie.

That being said, I would like to vote for Wallace. Problem: the rules require a ballot of three choices, and I don’t have strong positive opinions about anyone else listed. Negative opinions, several: Simmons, Ortiz and all of the first timers except Santana. Sentimentally, I’d love to vote for Minoso, but I can’t see him as being any better than his contemporary Larry Doby, who isn’t even on the secondary ballot. I would vote for Ashburn, Irvin, or Smith, but they’re not on the primary ballot. Thus, against my principles, a strategic vote:

Primary ballot:

Wallace

Allen

Rolen

Secondary ballot:

Ashburn

Irvin

Smith

I remember that previous departure from form, nsb, and I appreciate the vote for Wallace.

I hadn’t registered that Doby was now absent. I’d like to propose a particular form of a Redemption Round that would apply to him.

B-Ref has now incorporated Negro League stats with MLB ones (I don’t know how Stathead and FanGraphs handle this, cause my stat nerd days are over). The Negro League stats don’t represent full value because the records are only partial, but that may be ok because we don’t have clear measures of quality for Negro Leagues either. When we initially assessed players like Irvin, Minoso, and Doby, their stats were MLB-only and the case for them relied in part on the valid but very general argument that we weren’t seeing their full career accomplishments. Now their figures for WAR, etc., have changed. Doby’s WAR, for example, has risen from 49.2 to 56.8–still probably an underestimate, but you can now see how Doby belongs on the candidate list straight out. His WAR is higher than Ortiz or Simmons (and Minoso’s), and his PA/WAR matches Rolen’s.

So perhaps a round to reexamine the leading transitional Negro League/MLB players is in order.

Looking at this question when the Negro League stats first started showing up on B-R, I was surprised how few transitional players there really were who had any appreciable amount of WAR in both the Negro leagues and the major leagues. Perhaps those WAR totals have fleshed out a bit more for the former, but I expect it will still be a pretty short list.

Yeah, after doing a check I see you’re right. Some guys I thought might do well didn’t have the MLB minimum for the Circle, and the Negro League WAR numbers are partial enough that they can only supplement a case. Paige and Campanella benefit a lot, but they’re already in. Irvin and Doby are the only ones I found where the numbers really make a difference for a qualifying player. Jim Gilliam might have, but his Negro League records are too fragmentary. (Maybe Hank Thompson.)

Anyway, Doby’s case for redemption is still strengthened by the new numbers.

Is #13 Clay Kershaw? He had a non-qualified season to start his career of 98 ERA+ and then reeled off seven in a row at a 162 clip

It looks like it’s Mordecai Brown.

My mistake. I took “modern era” to be post-deadball (1920-present) – as opposed to 1900-present.

Brown is correct. He extended that streak beginning his career to 8 straight qualified seasons (1903-10) with 125 ERA+.

One more quiz question on the board, concerning Dan Johnson. Not surprised it’s the last question, since this player’s career was so inconsequential it seems a miracle he lasted 10 seasons, especially since the last six were in his 30s.

Johnson’s counting stats are underwhelming, as would be expected from a career of fewer than 500 games and 1500 AB. But he does seem to have had a few valuable skills, with a career 13% walk rate and 4% (of AB) homer rate, the latter translating into a blast every week to 10 days if he were playing everyday. He also struck out less than a lot of players from the recent past, with a 15% (of PA) whiff rate. Johnson also had a propensity for delivering sac flies, one of only 9 retired players with SF numbering more than 1.5% of AB in a 1000+ PA career. Altogether, works out to a 99 OPS+, so maybe the question should be not how he lasted so long, but, rather, why he played so little?

Ralph Houk spent 7 consecutive seasons with the Yankees with fewer than 30 games played and he had 6 consecutive seasons with fewer than 10 games played.

Funny, the first guy I checked was Charlie Silvera. Charlie got some WS $$ 1949-1953

During Silvera’s tenure with the Yankees (1948-1956) his career BA was .291. The only AL catcher with a higher BA with at least 400 plate appearances was Yogi with .294.

For the record, the answer to question 14 is Russ Morman, with 8 straight seasons of 40 or fewer games, including one or more at 1B. Morman played from 1986 to 1997, for the White Sox, Royals and Marlins.

15 years at AAA. Over 5,000 PA. .302 / .376 / .495 / .871

Morman must have wondered what coulda been had he been given the chance.

He was blocked in Chicago by a rapidly declining Greg Walker, blocked in KC by the tail end of Brett, then continued to mash at AAA, but even the expansion Marlins didnt see investing time into a mid-30s journeyman…

Main: Wallace, Randolph, Santana.

Secondary: Ashburn, Coveleski, Irvin.

It looks to me as though Wallace has entered the Circle and we’ve likely completed our work with regard to the Deadball Era.

Perhaps we’re through.

There are still a few players from the dead ball era that could perhaps be considered in our next redemption round. See the lists below:

Everyday players

Pitchers

Half a dozen guys on those lists with as much argument as most of our current group.

I agree, Voomo. I somehow had a comment deleted just now, but the gist was that although there are viable candidates on Doug’s list, the nature of the conversation here has changed. It used to be that the old-time players came to our attention in the context of their birth-year pool. Wallace came up when HHS was focused, round after round, on late 19th century / early 20th century players, so Wallace’s career had context.

And conversation was much more detailed then. I went back to look at the 1873 round when Wallace appeared, that was in 2015. You were first to comment on him, and the reply from one poster was, “Despite my best efforts, I can’t get too excited about Wallace. Basically, I can’t see where all that WAR is coming from. I’m going wait to vote, but I think I’m going to move on from Wallace.” But Doug began advocating for Wallace as a viable candidate and as the conversation went on and on, Wallace’s credentials kept coming under examination (along with others’) — by the end that skeptic wound up voting for Wallace! (Who was that, now? Someone with the ridiculous handle e pluribus munu. . . . Wonder what became of him.)

Wallace gained more rounds by staying in the conversation while the obvious deadball stars moved into the Circle, but then he began to lose ground (like Luis). I’m pretty sure Wallace would have disappeared amidst the light discussion of recent rounds if I hadn’t made a complete pest of myself pushing him forward until four old-timers here shoved him across the finish line. To get a deadball era star in the running from a standing start now would take an even bigger pest, and I’m not sure anyone can outdo me in that category.

I’m kind of lukewarm about the prospect of an additional number of, at best, borderline names on the COG candidate role. Fred Clarke is actually a superior candidate to any we now have, according to YT, but otherwise . . . ?

In its inception, the COG was supposed to be more selective than the HOF. That’s one point. A well-known weaker one—but I’m mentioning it anyway—is that the HOF has done a miserable job in its selection, which irks the heck out of me.

This is no solution, but I’m going to name the players currently in neither Circle nor Hall whom I think belong in Cooperstown, at least, whether they pass the COG test or not, and I invite anyone else to make their own suggestions.

Sherry Magee

Wally Schang

Urban Shocker

Ken Boyer

Dick Allen

Luis Tiant

Reggie Smith

Dwight Evans

Keith Hernandez

Thurman Munson

Rick Reuschel

Interestingly enough, the careers of the last seven overlap. What does that say about the blindness of the baseball writers to the players of the 1970s and 1980s?

To respond to your last question, nsb, and granting your premise that all of these players deserve to be in the Hall (which is reasonable), I wonder whether a contributing reason is the growth in the overall size of the player pool. In 1960 there were 16 teams; by 1978 there were 28. That’s a pretty sudden increase of ~75% in the number of regulars playing. I think Hall judgments are, in practice, about both absolute and relative quality, and the relative elements kept many BBWAA voters from expanding their ballots towards the full ten available slots. It’s only recently (in the 30-team era) that we’ve had frequent years with 3-4 inductees, and the players you list have long been off the ballot.

Bob,