My previous post on the 1893 adoption of the 60 foot 6 inch pitching distance focused on the impact to pitchers. This follow-up post looks at batters and how their offensive stats were affected by the longer pitching distance. More after the jump.

To briefly recap, the 1892 season, the first with a new 12-team National League, saw teams score at a rate of 5.1 runs per game. The next year, the first with the new pitching distance, offense ballooned to 6.6 runs per game, then 7.7 R/G in 1894 and back to 6.6 R/G in 1895. From that point, runs drifted lower, returning to close to 1892 levels by 1898.

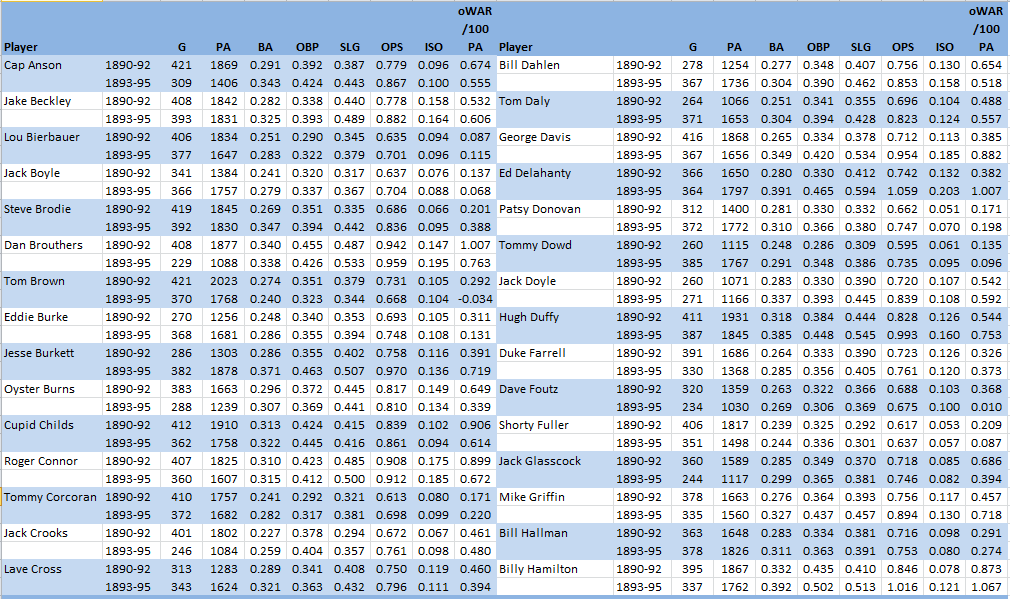

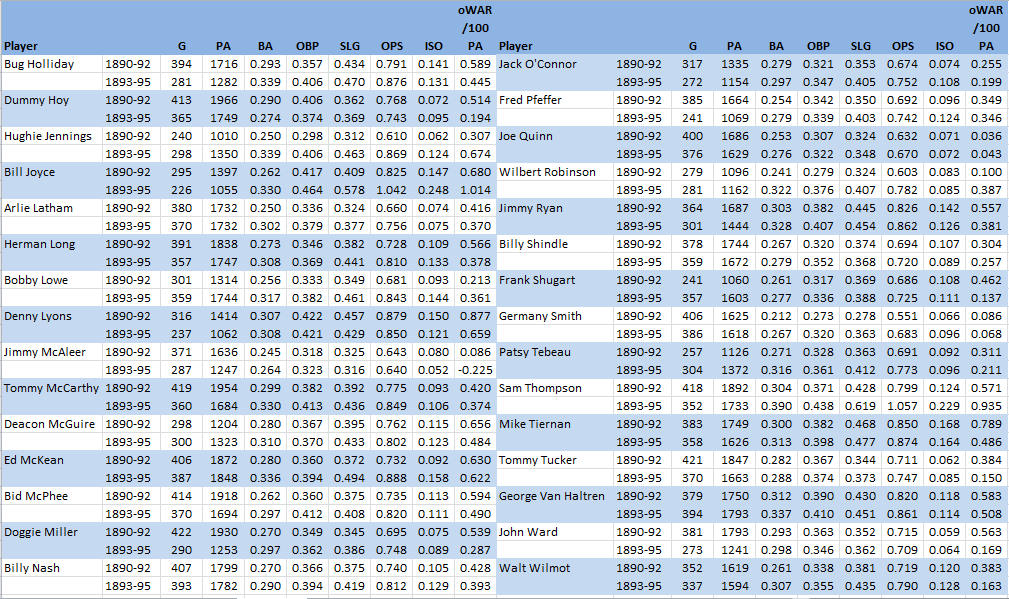

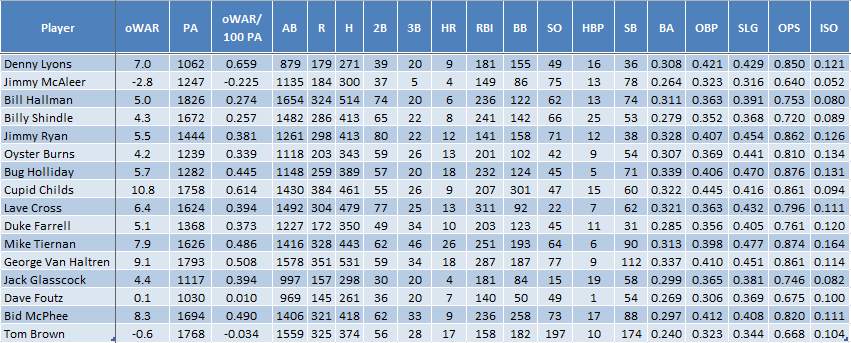

For this analysis, I’ll be looking at the 1893-95 seasons in comparison to the preceding years, using a study group composed of the 60 batters with 1000 PA from 1890 to 1892, and also from 1893 to 1895. Here are those players, listed alphabetically, with their rate stats for those two periods.

So, just about all of these players posted better results in the second period, with 57 of 60 posting a better BA, 51 a better OBP, 55 better slugging and 53 a better OPS. Fully 49 of the 60 players were better in BA, OBP and SLG. But, it’s a different story for the context adjusted oWAR measure, with barely a third of the players (21 of 60) posting a better result in the 1893-95 period.

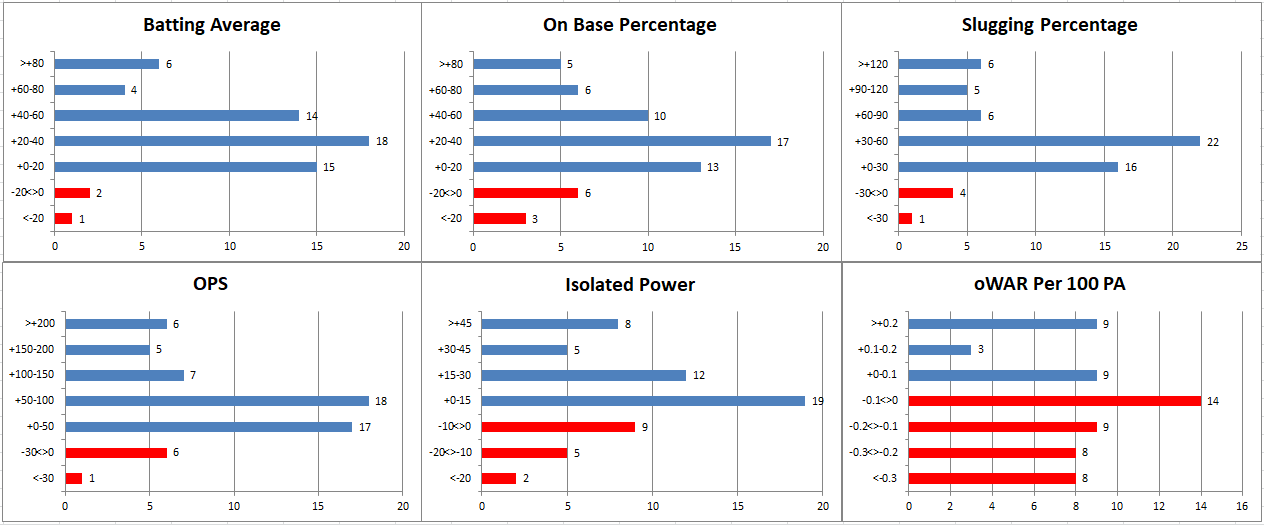

The charts below will give you an idea of the magnitude of those improvements.

A bit more than half of the players saw their BA improve by up to 40 points, and another 40% improved by more than 40 points. Similar story for OBP with half improving by up to 40 points and a third by more than 40 points. Almost two-thirds saw their slugging increase by up to 60 points with more than a quarter improving by more than that. All of that added up to an OPS increase of 100 points or more for 30% of the players, and by 50 points or more for another 30%. Improvements in ISO were more “isolated” with almost 60% seeing either a decline or no more than 15 point jump. But, a different story for WAR, with almost two thirds seeing a drop in their oWAR per 100 PA, including 40% who saw a drop of 0.1 or more (or more than 0.5 oWAR for a full season).

A bit more than half of the players saw their BA improve by up to 40 points, and another 40% improved by more than 40 points. Similar story for OBP with half improving by up to 40 points and a third by more than 40 points. Almost two-thirds saw their slugging increase by up to 60 points with more than a quarter improving by more than that. All of that added up to an OPS increase of 100 points or more for 30% of the players, and by 50 points or more for another 30%. Improvements in ISO were more “isolated” with almost 60% seeing either a decline or no more than 15 point jump. But, a different story for WAR, with almost two thirds seeing a drop in their oWAR per 100 PA, including 40% who saw a drop of 0.1 or more (or more than 0.5 oWAR for a full season).

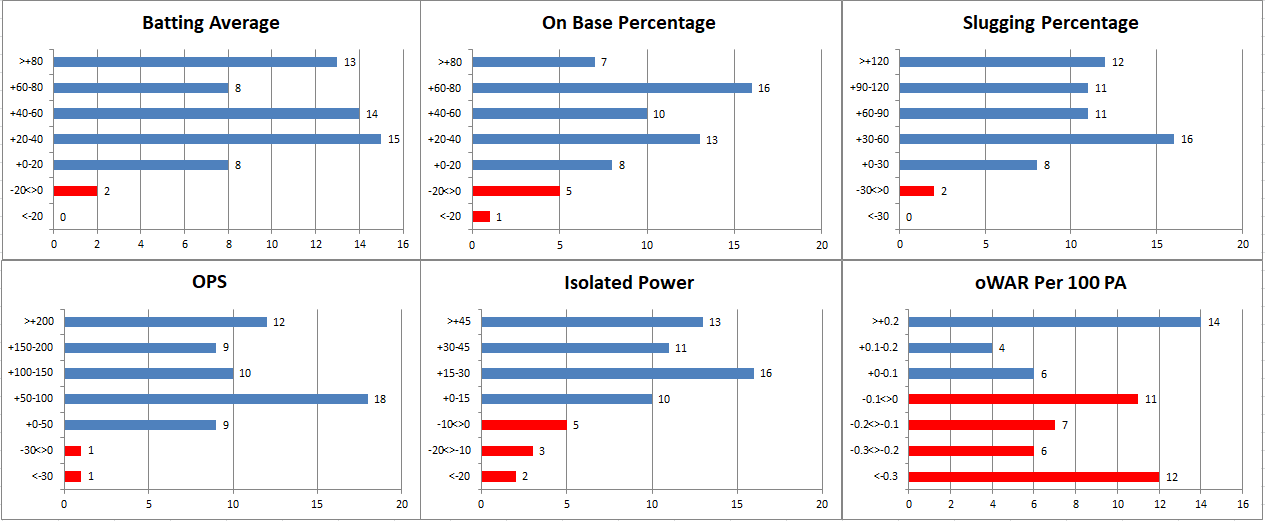

Some will have already surmised that there were more differences between these two periods than just the pitching distance. Indeed, each of the three seasons in the 1890-92 period was quite unique, with three leagues and 25 teams in 1890, two leagues and 17 teams in 1891 and one league and 12 teams in 1892. With those contractions, one would presume that the level of competition was a good deal stiffer in each succeeding season. So, to provide a more apples-to-apples comparison, here is what the same charts look like comparing the 1893-95 period to just the 1892 season for our 60 study players.

All of our study players saw action in 1892, with 50 compiling 500+ PA, 56 over 400, and only one below 300 (Dave Foutz at 234 PA). As the above charts illustrate, the 1893-95 improvements previously seen were even more pronounced when compared to the more modest totals posted in a stronger 1892 NL. Improvements in WAR, though, were only a bit better with just 40% recording a higher oWAR per 100 PA in the 1893-95 period.

All of our study players saw action in 1892, with 50 compiling 500+ PA, 56 over 400, and only one below 300 (Dave Foutz at 234 PA). As the above charts illustrate, the 1893-95 improvements previously seen were even more pronounced when compared to the more modest totals posted in a stronger 1892 NL. Improvements in WAR, though, were only a bit better with just 40% recording a higher oWAR per 100 PA in the 1893-95 period.

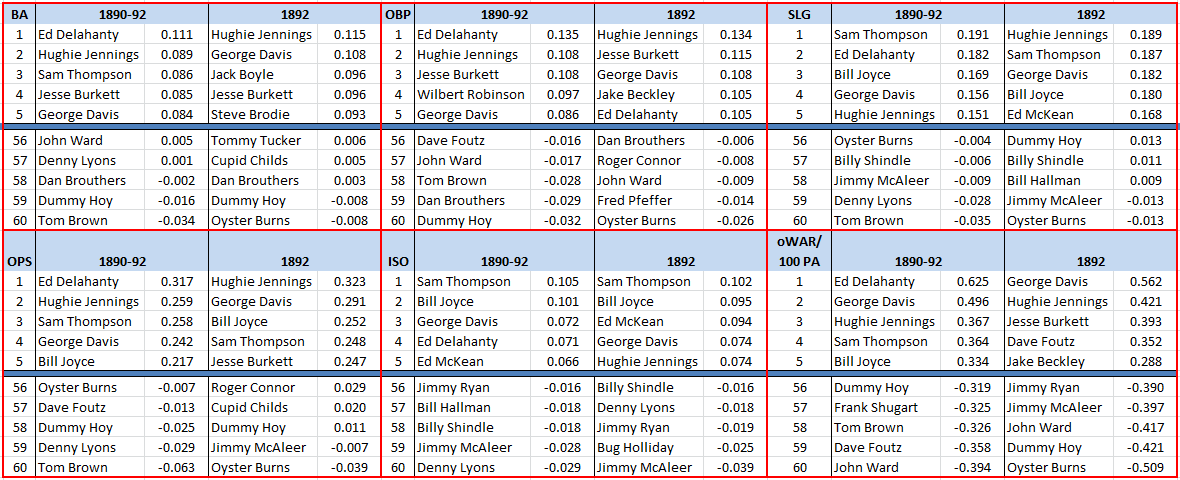

To give you an idea of the degree of improvement by the leading players, here are the top and bottom five of the 60 study players in improvement in each of these 6 metrics, comparing the 1893-95 period to 1890-92 and to 1892 alone.

- Sam Thompson, Ed Delahanty and Billy Hamilton led the offensive powerhouse Phillies who scored over 1000 runs (in a 130 game season) each year from 1893 to 1895. Alas, the Phillies didn’t have the same prowess on the mound and could finish no better than third.

- Thompson recorded three qualified seasons with 1.25 RBI per game, two with the Phils and one for the 1888 Detroit Wolverines; no other player since 1876 has even one such campaign.

- Delahanty recorded a .400/.500/.600 season in 1895, one of only four such qualified campaigns since 1876.

- Hamilton’s 198 runs scored in 1894 is the all-time record as are his four seasons with 100 or more steals. Hamilton twice posted triple figures in runs, walks and steals; Rickey Henderson, with three such seasons, is the only other player to do so even once.

- Hughie Jennings was the star shortstop on the Orioles teams that claimed three successive pennants from 1894 to 1896. Among his talents was getting plunked, leading the league in HBP five straight seasons, including 3 times with more HBP than walks.

- George Davis and Honus Wagner, both shortstops, share the record total of 16 seasons with 20 doubles and 20 stolen bases. Davis likely would have reached those marks a 17th time in 1903, but lost that season when ruled ineligible to play for “jumping” back to his old Giants team.

- Bill Joyce was possibly the most feared slugger of this period, drawing 284 walks from 1894 to 1896 (second to Billy Hamilton) while leading the NL with 47 round-trippers, many of them tape measure jobs. Joyce, who sat out the 1893 season in a contract dispute, totaled 31 WAR from 1890 to 1898, the most in a career of fewer than 10 seasons.

- Jesse Burkett‘s 240 hits in a 130 game season in 1896 was the record total until surpassed by Ty Cobb in 1911. No player in the modern era has matched Burkett’s 1.8 hits per game in a qualified season (or even in a season of just 50 PA).

- Ed McKean was Mr. Consistency for the Spiders, recording 258 to 284 total bases, 45 to 50 walks and 118 to 125 OPS+ each season from 1893 to 1896. McKean, Jack Glasscock and Germany Smith are the only players with 1500 games at shortstop before the modern era.

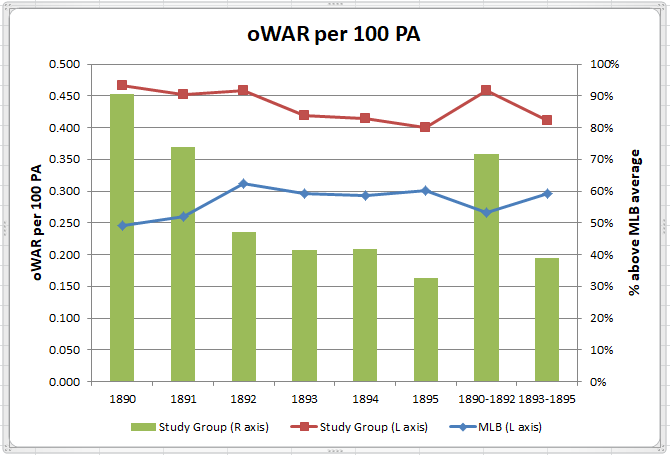

So, that is our study group. But, how representative is it of the majors as a whole? Here is our oWAR measurement for the study group and for MLB for this period. As expected, our study players who consistently commanded regular playing time performed well above the average major league player. As our study players aged (by 1895, more than one-third were aged 31 or older, and more than 20% were 35 and above), that gap narrowed from just above 70% better than the MLB average for 1890-92 to slightly below 40% better for 1893-95. Most of that narrowing, though, occurred not when the study players were oldest, but early in the study period, in 1891 and 1892. As noted above, those two seasons saw significant contraction in MLB teams, the effect of which is illustrated in the next chart.

As expected, our study players who consistently commanded regular playing time performed well above the average major league player. As our study players aged (by 1895, more than one-third were aged 31 or older, and more than 20% were 35 and above), that gap narrowed from just above 70% better than the MLB average for 1890-92 to slightly below 40% better for 1893-95. Most of that narrowing, though, occurred not when the study players were oldest, but early in the study period, in 1891 and 1892. As noted above, those two seasons saw significant contraction in MLB teams, the effect of which is illustrated in the next chart.

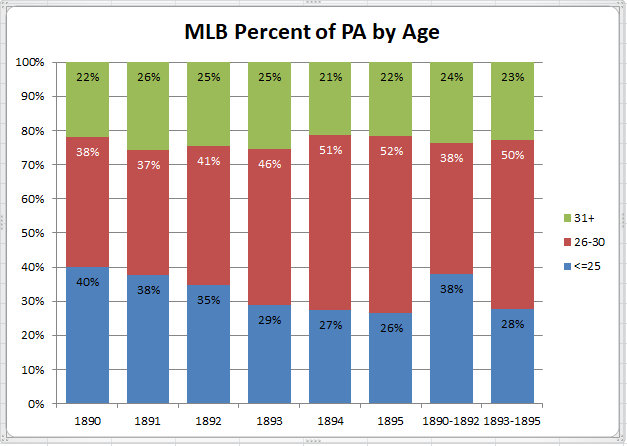

To fill those extra roster spots in 1890 and 1891, teams were turning to younger players, with those aged 25 or under actually getting more playing time than the age 26-30 group that is normally the “sweet spot” for the highest level of player performance. By 1893-95, the playing time for the under-25’s had declined by one-third from 1890-91 levels, while the 26-30 group had increased by about the same amount. The next chart illustrates how that reallocation of playing time was reflected in performance.

To fill those extra roster spots in 1890 and 1891, teams were turning to younger players, with those aged 25 or under actually getting more playing time than the age 26-30 group that is normally the “sweet spot” for the highest level of player performance. By 1893-95, the playing time for the under-25’s had declined by one-third from 1890-91 levels, while the 26-30 group had increased by about the same amount. The next chart illustrates how that reallocation of playing time was reflected in performance.

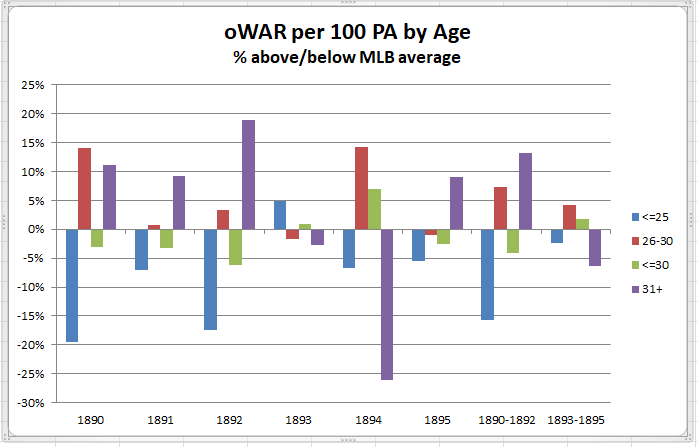

Note the large deviations in oWAR relative to the MLB average that are seen for 1890-92, with the under-25 group having the worst results and driving down the MLB average oWAR, paradoxically resulting in the age 31+ group performing above that average. With a more normal age distribution in 1893-95, the variance in oWAR between these age bands shrinks considerably (indicating a more uniform level of major league performance), with the age 31+ group now the weakest in performance as would normally be expected.

Note the large deviations in oWAR relative to the MLB average that are seen for 1890-92, with the under-25 group having the worst results and driving down the MLB average oWAR, paradoxically resulting in the age 31+ group performing above that average. With a more normal age distribution in 1893-95, the variance in oWAR between these age bands shrinks considerably (indicating a more uniform level of major league performance), with the age 31+ group now the weakest in performance as would normally be expected.

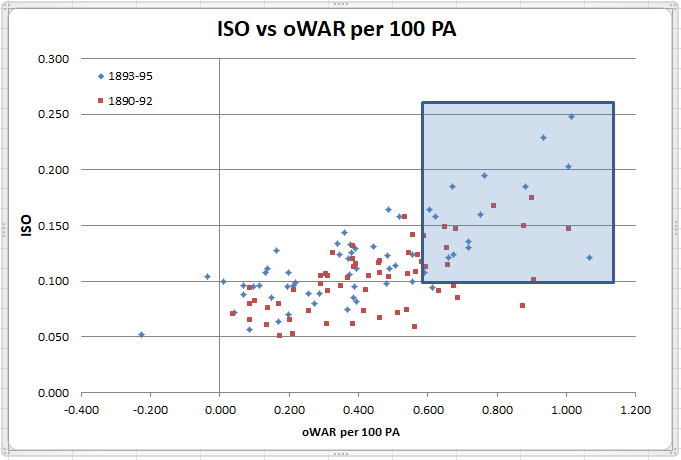

So, which hitters adapted best to the new pitching distance? The chart below of our study group players suggests that batters who were willing to go deep more often benefited their teams the most. The top results of 0.6+ oWAR per 100 PA (about 3+ oWAR for a full season) mostly belong to those recording at least 100 points of isolated power, There were 15 study players in this sweet spot for 1893-95 compared to just 10 for 1890-92. Note also that the top 6 ISO results for 1893-95 all surpass the leading result for 1890-92. Looking at ISO change from 1890-92 to 1893-95 shows this same relationship.

The top results of 0.6+ oWAR per 100 PA (about 3+ oWAR for a full season) mostly belong to those recording at least 100 points of isolated power, There were 15 study players in this sweet spot for 1893-95 compared to just 10 for 1890-92. Note also that the top 6 ISO results for 1893-95 all surpass the leading result for 1890-92. Looking at ISO change from 1890-92 to 1893-95 shows this same relationship.

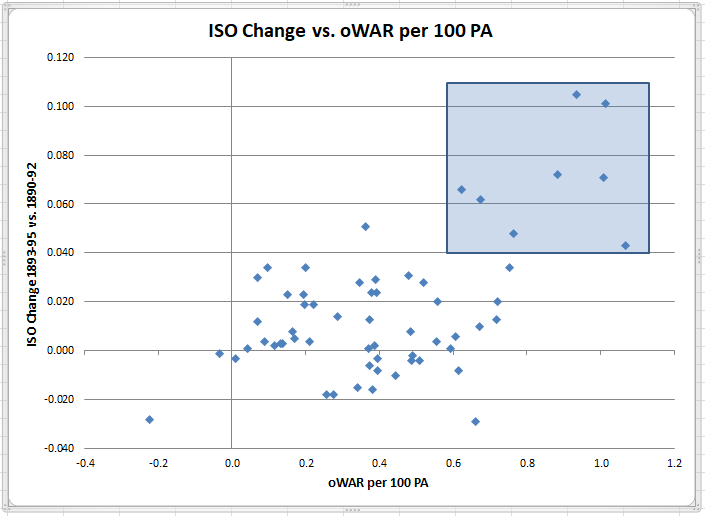

The above chart shows that increasing ISO, regardless of its starting point, generally results in more positive WAR, with the same 0.6 oWAR per 100 PA “sweet spot” corresponding to a 40 point ISO rise.

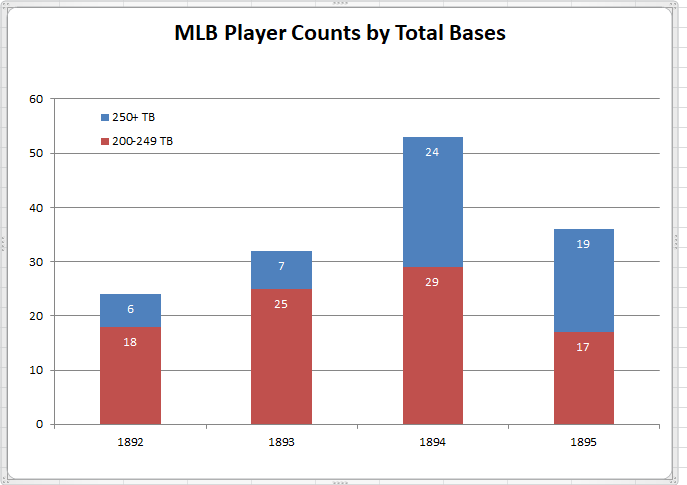

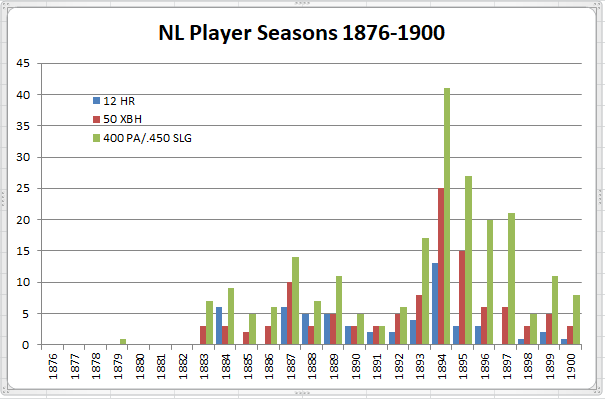

This increase in power was not seen only in our study group, as shown in the chart below of the number of MLB players in the 12 team NL with 200 or more total bases. The increase in these seasons starting in 1893 would have been more pronounced had the 150 game schedule used in 1892 not been reduced to the 130 games used for the next five seasons (1893-97). Some other indicators of increased power hitting are shown in the chart below.

The increase in these seasons starting in 1893 would have been more pronounced had the 150 game schedule used in 1892 not been reduced to the 130 games used for the next five seasons (1893-97). Some other indicators of increased power hitting are shown in the chart below.

There’s an enormous amount to take in here, Doug. The rise in offensive statistics in 1893-95 is, of course, no surprise, but the drop in oWAR levels among leading regulars is, although age may account for some of it. I’m just beginning to sort through it. Thanks again for all the work and for continuing the discussion on the 19th century.

One comment I think I can contribute concerns you ISO chart. While it makes sense that there would be a correlation between high ISO and oWAR, I’m not sure we can conclude that, “batters who were willing to go deep more often benefited their teams the most.” High ISO indicates extra-base hits, rather than long balls, and we’d need to know more about rates of fly outs to conclude that hitting long in 1893-95 was more productive than the norm. It also looks to me that there is a close correlation between the scatter patterns of 1890-92 and 1893-95 on that chart, and that if you indexed ISO against a median for each year, the patterns might be more or less the same.

I agree that the relationship between ISO and WAR is strong, and holds both before and after the change in pitching distance. To make my point clearer, I’ve added a chart showing a similar relationship between ISO change and WAR; that is, regardless of what ISO was before the pitching change, increasing ISO after that change correlates with increased oWAR.

I’ve also added another chart showing additional power-related metrics that spiked up in the first years after the pitching change.

Uff da! More data. It’s going to take a while to figure out how to work with all these themes. I’m especially interested in looking in more detail to see how different age cohorts and types of players at the 1892/93 border handled the changes.

One further comment in the interim: It may make more sense to work with OPS+, rather than oWAR, since oWAR (like dWAR, but unlike OPS+) embeds positional adjustments, which vary from year to year, usually just by a little, but with the abrupt changes involved here, perhaps by more than usual.

Great data. Wanted to put something out to the esteemed panel. There are considerable number of players who got a substantial boost. But there are also several who didn’t. I’m interested in that cohort. Are there commonalities between that group? Age, size, or anything else? The rising tide didn’t lift all boats. Why not?

Indeed. More than one quarter of the study group (16 players) saw their ISO decline in the latter period. Here are their totals for 1893-95.

– Fourteen of those sixteen saw a rise in all three slash components, but all of them saw a bigger increase in their batting average than in their slugging percentage (obviously)

– Only one of the sixteen showed an increase in oWAR/100 PA in the second period

– Only four of the sixteen slugged .450 or better in the second period, and none slugged .500

– In sum, these guys were hitting more singles (9 of 16 were under 100 XBH over three years) while the league was getting more XBH

I’m working through the list of players to understand better whether performance changes were correlated with age, position, and so forth. That’ll take a while. But in the meantime I did want to note that in talking about the rise in ISO, we are speaking of a very ephemeral phenomenon, one that is really significant only for 1893-97 — which Doug did specify in talking about the R/G rise in his post: I’m not writing this to dispute his analysis.

These are league ISO figures for the 12-team NL, 1892-99, with the % deviation from 1892 added:

1892 .082 —

1893 .100 +21.0%

1894 .126 +52.4%

1895 .104 +25.6%

1896 .097 +17.6%

1897 .094 +14.5%

1898 .076 -7.3%

1899 .084 +1.9%

(Note that the % figures are not year-to-year, but indicate change in ISO from 50′ pitching distance.)

ISO figures will plunge even lower than 1898 in the next decade, winding up 17-20% lower than 1892 for the 1906-09 seasons. These are just the deviations from the 1892 base:

1900 +5.6%

1901 +6.4%

1902 -6.9%

1903 +2.4%

1904 -9.7%

1905 -8.5%

1906 -17.9%

1907 -22.7%

1908 -19.9%

1909 -18.2%

I think what we’re seeing here is a short-term bump in ISO as a result of the 1893 pitching change, which starts to wear away at a relatively uniform rate and then is simply reversed. Superimposed over this is the unusual hitting surge of 1894 that was discussed at length on the last string, and which gives the 1893-95 era a profile that, in my own view, was probably distorted by tinkering with the equipment (much like the case with 2017), perhaps mirrored in the years after 1905. I think we’d do better to treat 1894 as a singleton case, discount the 1895 (vs. 1892) percent figure by about 20%, and see the adjustment of 1893-97 as represented by a series such as this: +21%, -?-, +20%, +18%, +15%. Then we need to explore what happens in 1898 and 1906.

Thanks for the response and nice work. The whole thing could be noise, or it could be something that pitchers later learned to adapt to, erasing whatever short-term advantage hitters might have, or there could be other intervening factors later on. One thing that strikes me as possible is that the cohort that didn’t positively change because for some reason they were unable to physically to take advantage, or perhaps had a “small ball” style of hitting, or even were were disproportionately users of the flat bat. You’d love to see spray charts.

There’s no question that some players with lower oWAR in the later period were simply aging (like Dave Foutz, 35 in ’93, or Jack Glassock, who was 33, or Tom Brown, who was 32). But there are other things to think about. We take OPS as a far better indicator of a player’s contribution than Batting Average, but in the 1890s, BA was the leading standard, and hitters may not have seen themselves sacrificing anything by adding singles in larger numbers, while letting XBH fall where they may. I’d think Lave Cross would be an example of that (this would fall under “small ball style” play, which would come back into fashion before Cross retired in 1907), and his oWAR may also have been affected by his gradual shift over this period from catcher to third base.

It seems to me that oWAR is not an absolute measure, but indicates a player’s share of league productivity. When you’re looking at a four to six-year stretch, there are many reasons a player’s productivity could fall or rise in comparison with other players (which is itself a changing population), independent of rules shifts or the speed with which players spotted and exploited new opportunities they created. I don’t know that there’s any way to analyze this except to start on a case-by-case basis.

I’d have originally thought the lagging cohort would be all punch-and-judy types, singles hitting leadoff guys. And that’s certainly true of, say, Dummy Hoy. But it’s not quite true of a guy like Oyster Burns, who was more of a 19th century power hitter (good number of triples, actually led the NL in homers during the 1890 season when a lot of his competition for black ink was in the Player’s League).

And I’ll never miss a chance to mention that Oyster Burns is the best player to ever play for the mighty Wilmington Quicksteps of the Union Association (2-16 record before folding up shop). Wilmington! It’s a wonder that the Union Association failed to compete with the big boys when it had powerhouse cities like Wilmington and Altoona, PA on board.

(That’s not quite fair to the UA, who also had teams in St. Louis and Boston and Philadelphia and Kansas City and Baltimore and Cincinnati and…well, you get the picture, but seriously – Altoona!)

Altoona makes sense in that it was a railroad hub. Has a minor league team there now.

I mean, it’s not the smallest place to ever have a “major league” team – I believe that honor goes to mighty Keokuk, Iowa – but railroad hub or not, it’s a tough sell as a ‘big league’ town.

Actually, CC, if we’re going to include the National Association, the Rockford Forest Citys of 1871 (starring Cap Anson), played in an Illinois town with a population one-third smaller than Keokuk (11,000 vs. 17,000 in 1870). But Middletown, Connecticut seems to win the prize. When the Mansfields took the field in 1872, featuring future Hall of Famer Orator Jim O’Roarke, they were representing a “city” of under 7000.

I knew about Rockford, but didn’t realize they were that small back then, since they’re currently a much bigger city than Keokuk.

I suppose all these one horse towns having teams is one reason they decided not to count the NA as a “major” league, but the UA had the same issues, and at least the NA lasted five seasons.

Yeah. The UA clearly was not a Major League, in the sense we mean, and it shouldn’t have been classed that way in the Macmillan Encyclopedia, which I believe is the authority other sources follow. The problems with changing that now are that it did have some real major leaguers and it’s tough to change their lifetime stats now, and the quality of all the leagues was diluted in 1884, making the UA less amateurish inn context than it would otherwise seem. For example, is it fair simply to throw out Charlie Sweeney’s 24-7, 165 ERA+ pithing record and his 165 OPS+ batting, when his early season 1884 record in the NL was 17-8/183 ERA+, with 126 OPS+?

I hadn’t mean to send off that last message without adding that the NA’s problems weren’t only ones of quality: if there was a major league in 1871-75, it was obviously the NA. I think the main issue was governance: wild as the game was in the later 1870s and the decade after, it was nothing like the NA, where fixed games and umpire intimidation made everything on the field suspect. The formation of the NL was about changing the business model and monitoring standards. (But in 1901, there were still enough problems that I believe this was one of Ban Johnson’s selling points for starting the AL.)

Well, Altoona was indeed a railroad hub (learn something new every day — check!), but I’m not sure it makes sense. Its population was about 25,000, half the size of Wilmington (which, I think, does make sense, at least as much sense as Toledo, which was in the AA in 1884, or Troy, which was in the NL up till 1882). I doubt there was likely an idea that folks would take in a ballgame while switching trains.

I’ve been trying to figure out Burns’s career, and why he wound up on Doug’s list. He had a bad year in 1893 at age 28, but it’s hard to say that it was the rule change that caused it: he missed quite a few games, and it could have been an injury. He came back strong in 1894, fully competitive in the strange environment that year (126 OPS+), though not the outstanding offensive force he had been when he was in most of his 20s (147 OPS+ ages 22-27). Then he seems suddenly played out by 1895 and left MLB at age 30.

Brooklyn, for which he’d been a regular for seven seasons, seems to have released him after a slow start over just twenty games in ’95 (29 OPS+). But then the Giants picked him up and he did fine over thirty games (112 OPS+). It may be that he was hampered by injury or an ailment early in the season and signed on with the Giants late, having recovered. But the Giants sold him to a Minor League team for $1000 in the off-season — the deal may have been connected with Burns’s desire to manage, since that’s what he did with his new team, Newark, where he was also terrific at the plate in ’96.

There is no SABR bio to explain why Oyster burnt out so suddenly, but many players of his day drank themselves out of a career. Burns, however, went on to manage in the Minors in ’96 and ’98, was an NL umpire throughout 1899, and lived to be 64 — all that doesn’t rule out drink as a cause of his decline, but it doesn’t suggest it either. Burns had regularly filled in as a middle infielder through 1892, but in 1893, he did that only once, and never thereafter. That may suggest an injury in ’93 that hampered his mobility a bit, but his 14 triples in ’94 still indicate fair speed, and he was stealing lots of bases in the Minors in ’96-97.

In any case, Burns is a good example of the complexity you see when you look at individual cases among the 1890-92/1893-95 cohort. Something went wrong, but the ’94 season suggests the causes may have been unrelated to the rule changes of 1893, even though that was not the season for Oyster.

In discussing Oyster Burns, who’s on Doug’s list because his 1893-95 ISO is lower than 1890-92, I should have addressed his ISO pattern specifically:

…………….1890…….1891……1892…..1893……1894……1895

ISO………..180……….132……..138…….142……..146……..084

Obviously, the contrast is not between ’90-2 and ’93-5, it’s between 1890, the year Burns won the HR title with 13 in a three-league talent pool, and 1895, when he said his MLB goodbyes. The middle four years, two on each side of the rule change, are consistent when it comes to ISO, with a modest rise of about 10 points following the rule change.

The top similarity score for Burns is another player on Doug’s list, Denny Lyons, a third baseman. Lyons has these ISO numbers:

…………….1890…….1891……1892…..1893……1894……1895

ISO………..177……….140……..139…….122……..132……..091

Both Burns and Lyons were standouts in their respective, talent-diluted leagues in 1890, Oyster the NL HR king and Lyons the AA OPS leader (heading both OBP and SLG leaderboards). Those years are outlilers for both. Lyons switched leagues in 1892 (going to the NL as the AA folded), and his OPS+ reflects the tougher context:

…………….1890…….1891……1892…..1893……1894……1895

OPS+……..193……….150……..129…….131……..113……..99

Looking at Lyons’ OPS+ numbers, there is no visible impact of the rule change in ’93, although the ISO numbers suggest there may have been one. But by ISO, Lyons more or less recovers to his NL “norm” (1892) in 1894. But in ’94, Lyons was actually playing only half time, and he had a lousy season — he was only quarter-time in ’95. Then he bounces back in ’96, playing full time, with a 121 OPS+; however, his ISO remains pretty low, at .112. 1897 is his swan song: 37 unimpressive games, with an OPS+ of only 89 — but his ISO zooms up to .153. (He follows with some uninspired years in and out of the Minors.)

Like Burns, Lyons has no SABR bio to help us understand the swings in his career, which do indeed come quite close to Oyster’s (the two even died within two months of one another, 30 years after their careers ended). But, as in Burns’ case, it does not appear that the rules changes of 1893 were a major factor on his relative standing among his peers. His ISO does decline a bit in his one full season in the 1893-95 range, but his OPS+ actually rises slightly — his ISO and OPS+ figures are strangely correlated.

Just a question here. With a pitching distance of 50 feet is it possible to have time to swing at a fastball or were the pitchers not pitching as fast as they do now?

Without radar guns, we really only have people’s recollections. You’ve got a link from one generation to the next, but there’s always a problem of guys looking back at their past with rose colored glasses. Player X batted against Walter Johnson as a wet-behind-the-ears teenage busher, then batted against Bob Feller as a grizzled vet, and swears Johnson was faster. Player Y has the same experience, but faced Feller as a rookie and Koufax as a vet. Player Z has the same, but now with Koufax and Ryan.

That being said, there are players who swear Amos Rusie threw just as fast as Walter Johnson. And IIRC that was one of the reasons for the change to 60 feet 6 inches – players didn’t feel safe facing guys like Rusie from only 50 feet away.

Did Rusie throw in the mid to high 90’s? I think it’s at least possible that he did. In other athletic endeavors, we’d never believe that someone from the 1890’s could match a modern player. 21st century sprinters are worlds faster than late 19th century sprinters. Swimmers are faster. Powerlifters lift more. But throwing a baseball isn’t quite as simple as running in a straight line, and we haven’t seen the kind of progression in maximum pitch speed that we have in other athletic achievements. If pitch speed evolved the same way sprinting has, or swimming has, we’d see guys throwing 120 MPH now. But we know that the absolute fastest pitcher now (Aroldis Chapman) isn’t that much faster than someone like Nolan Ryan – he’s faster, but only be a few MPH. And Aroldis is a freak – he’s the absolute fastest pitcher on the planet.

Average fastball velocity has undoubtedly been going up steadily (though again, at some point it will level off – perhaps it already has. We’re not going to ever have a league where everybody is Aroldis Chapman) – today you’ve got multiple guys, sometimes more than one per team, who can touch 98+ MPH. For most of baseball history, there was probably only one or two guys in the league at a time that fast, if any at all. With some exceptions, a guy that can’t at least throw in the high 80’s is going to get laughed out of even a minor league tryout. I believe lots of guys in the 19th century and the early 20th century probably succeeded with what we’d now considered batting practice fastballs.

But I think there’s a good chance that someone like Rusie was throwing in the mid 90’s.

No way Rusie was throwing in the 90s consistently AND averaging 500 innings a year (as he did from 1890 to 1894). Also, he threw a lot of pitches, leading 5 times in both strikeouts and walks, incl. both in the same season 4 times.

I don’t know, Doug. Rusie was pitching 500 innings a year only when the pitcher’s box was in place. We really don’t know what sort of demand on the arm was involved with the shorter distance (an effective difference of about 5 feet). In ’93 and ’94 his IP fell to 482 and 444, and were in the 300s his last three seasons.

While Rusie led the NL in Ks and BBs, his total rates per 9IP were actually much lower than was the case for Feller and Ryan when they were pitching well over 300 innings. For example, in 1893-94 Rusie had about 8 K+BB/9IP; compare Feller 1946, with a 12.1 average over 370 IP, or Ryan in 1973-74, averaging 15.2/9IP over 330 IP.

I believe it’s generally accepted that power pitchers in early baseball paced themselves much more moderately than pitchers in the HR era. Rusie may have thrown his fastest on a somewhat lower percentage of pitches than later fireballers, but I really don’t see a bar to believing he regularly threw fastballs in the 90s.

As for Richard’s question, a batter who sees a 100 mph fastball today has 0.412 seconds to react. A batter who saw a 90 mph fastball with the effective pitching distance at 55.5′ (the push-off point for a pitcher prior to 1893) had 0.420 seconds. So allowing that peak fastball pitchers may be about 10 mph faster now than they were prior to 1893, batter reaction time would have been about the same.

I decided to run my own numbers. By observing photos of pitchers delivering a pitch it can be observed that the long stride they take indicates that the distance from the point of release of the ball from the pitcher’s hand to the plate is about 5 feet closer than from the rubber, giving a total distance of 55.5 feet to the plate. 30 mph = 44 fps so a 100 mph pitch travels at (100/30)*(44) = 147 fps. The reaction time is 55.5/147 = .378 seconds. Doug mentioned in a prior post that the distance prior to 1893 was 50 feet. Assuming the pitchers then also took a long stride, the actual distance traveled by the ball was 45 feet. A 90 mph pitch travels at 132 fps and the reaction time would be 45/132 = .341 seconds. Is a time difference of .037 seconds significant?

Richard, prior to 1893, pitchers delivered from within a “box,” the front line of which was 50 feet from home. Their front foot could not cross that line. Moreover, their rear foot could not cross a line drawn 55.5′ from home. That 55’6″ is the equivalent of the pitching rubber being at 60’6″, and therefore the difference in distance between 1892 pitching and today’s was five feet, not the 10.5 feet you’re calculating.

I was calculating from 60’6″ for contemporary 100 mph pitches, but your calculation of 0.378 seconds is surely more precise. For a 90 mph pitch in 1892, the time would be 50.5/132= 0.383.

epm: Thanks for the update.

Those calculations can probably give us an upper bound on Rusie’s velocity – we know he was hard to hit, but not impossible, so he couldn’t have been throwing, say, 100 MPH. Of course, we’d have likely come to that conclusion anyway, but the reaction time numbers give us something like complete certainty.

As to Doug’s point, I think looking at some of the figures epm gave, Rusie probably wasn’t throwing that many more pitches than Feller or Ryan. I doubt we’ll ever know his average velocity – what was he throwing on pitch 150? – but if Feller threw 98 MPH in the 1930’s over 370 innings while walking or striking out half the county, I don’t see it as improbable that Rusie threw 95 MPH (at his max) in the 1890’s over 480 IP while only walking and striking out the village instead of the county.

I saw online John Thorn wrote about the box and the fact that the change in 1893 was really a change of 5 feet, not 10.5. He also posited that from the hitter’s perspective, Rusie from the 1892 distance may have seemed like the fastest pitcher ever. Given epm’s calculations, that seems correct – if Rusie was even at 92 or 93 MPH, he’d have looked slightly faster than Chapman does to a modern batter. And if the average batter was used to seeing stuff in the mid 80’s, you could understand why people might exaggerate and claim Rusie was just as fast as Feller. (There’s also the fact that the human eye just isn’t quite capable of telling the difference between 92 MPH and 98 MPH – if we see them right in a row, we can tell one is faster from context, but remove the context and the eye simply isn’t that precise.)

Doug’s posts on the 1892/93 transition are, I believe, in response to my hope that HHS would begin digging deeper into 19th century baseball, perhaps looking towards a new CoG wing on that basis. Few, if any, of us know much about the 19th century, and it’s hard to be interested without familiarity. One of the most exciting things I recall about baseball is buying the 1969 Macmillan Encyclopedia and discovering that the 19th century was there in rich detail – a whole world of baseball to explore that had been practically invisible to me before (although my Dad had a habit of calling out “Slide, Kelly, slide!” when we’d go to games).

In this comment, what I’d like to do is explore some individual players: the nine shortstops who are part of Doug’s “study group,” and my purpose is both to see how these players fit the general theme of Doug’s “birth of the power hitter” take on 1893-95, and simply to bring them into the conversation as players of the “modern,” post-1893 game. I wrote about some of these guys during the CoG discussion, as a way of contextualizing arguments for Bill Dahlen and Bobby Wallace, but here I’m focusing on their careers more generally, though focusing on the 1890s and excluding the decade of 1900-10, when Dahlen and Wallace were still exemplary figures.

For each player, I’ve started with figures for career WAR, how old they were in 1893, and their career span, indicated by when they first exceed rookie quotas and when they last have that level of play — some of these guys were on their way out, which is why they decline after ’93; others were just starting up, which is why ’93 on looks so much stronger than before, but most cases are more complicated than that.

Tommy Corcoran (WAR: 20.6; age in 1893: 24; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1890/1907)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….68…….93…..…71………82……88…….73

ISO… .083… .121… .042….. .081…. .132… .080

Corcoran was one of the premier shortstops of the 1890s, mostly for Brooklyn and Cincinnati: a weak hitter (79 OPS+, 1890-99 [ages 21-30]) with excellent defense (74 Rfield in 1890-99). His OPS+ bounces around: 1892 (71), 1893-95 (82: 82/88/73); ISO bounces even more: 1891 (.121), 1892 (.042), 1893-95 (.099: .081/.132/.080). Corcoran is an example of Doug’s point about ISO increasing with the 18983 movement of the pitcher. However, note that Corcoran’s sixty percent ISO jump in ’94 yielded just an 8% bump in OPS+, reflecting the league-wide ISO burst of 26% over 1893. Still, Corcoran’s figure put him over the league ISO (which was the case also in 1897-98, when his OPS+ was 79). Despite declining OPS+, Corcoran remained a defensive whiz and a fixture in Brooklyn and then Cincinnati until fading out after a poor 1906 season, age 37.

Bill Dahlen (WAR: 75.4; age in 1893: 23; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1891/1909)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….–……111…….139…….118..…138…….79

ISO… —-….. .129….. .131..… .151…. .207… .116

We’ve said a lot about Dahlen in CoG discussions, so I’ll let these numbers speak for themselves. Dahlen followed these seasons with high ISO numbers in ’96-7 (.200/.188), but never returned to that level: his highest over the following eleven full seasons was .112, and his career number was .110. His OPS+ for 1896-98 was 137, approximately matching his figures in 1892 and 1894 (very different hitting contexts), and then 98 for the remainder of his career. Dahlen is one of only four regular shortstops to play for a NL pennant winner in the 1890s, which he did in 1899, his first year with the Brooklyn Superbas.

Shorty Fuller (WAR: 7.1; age in 1893: 25; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1888/1895)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…97.……58…..….74………66..…..74…..….53

ISO…. .057…. .059… .043… .063… .074…. .037

Shorty’s career was short (only 207 games fall outside the range here), and the reason is not mysterious: he couldn’t hit, and lasted seven full seasons only because he was a good fielder. He moved from the AA Browns to the NL Giants in ’92, and it’s interesting that his OPS+ actually improved in the tougher environment, although not to the level he’d reached in the talent-thin 1890 season. His OPS+ declines in ’93-’95, from 76 to 64, but only because of the outlier ‘92/’95 seasons at the two ends. (His three-year oWAR/100PA falls more dramatically from .209 to .087, likely a disparity caused by switching the comparison from average to replacement value, and actually understated a bit because the positional component for SS is figured in.) After his weak 1895 season, he started ’96 terribly (OPS+ 29 in 18 games) and was out of the league at age 28 (with a short period in the Minors after).

Jack Glasscock (WAR: 62.0; age in 1893: 35; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1879/1895)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…147….…86…..100…….113…….73…….75

ISO…. .104…. .065… .081..… .092… .081… .057

Glasscock’s prime was in the 1880s, topping out in the talent-thin 1890 season. He was a terrific defensive shortstop – perhaps the greatest of the 19th century – but by the time of the 1893 rule change in his age 35 season, Glasscock was about at the end of his string, and a hand injury in 1891 had reduced his effectiveness. He played only 87 games in ’94 and 43 in his final season the following year. It’s hard to judge whether the bump in 1893 was due to the rule change, or due to a trade to Pittsburgh after one season with St. Louis and about forty percent of ‘93: Glasscock’s before/after-trade figures for OPS+ during the ’93 season are 96/124, and for ISO .067/.109. (Glasscock was used to trades: he played on nine different teams in a seventeen season career.) He’s on Doug’s list of players whose ISO declined after 1893, but in Glasscock’s case, this is surely explained chiefly by aging.

Hughie Jennings (WAR: 42.3; age in 1893: 24; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1891/1902)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….–……110………71…..…26..…..110……143

ISO… —-….. .083..… .051…. .042….. .144….. .127

Jennings fits no pattern whatsoever. He was young when the rule change occurred (age 24), and the 1893 season obviously provided him no bump at all – he had only 154 PA, split between two teams. Then the Louisville Colonels gave up on him, and he became a sparkplug of the great Oriole pennant winners of the mid-1890s. His OPS+ for ’96-’98 was 149 (he batted .401 in 1896, but his OPS+ is almost the same all three years), yet his ISO drops to .097 – walks and 143 HBP in three years are probably the chief reasons. After that, at age 30, Jennings was pretty much an average player, mostly part-time; hie fielding excellence goes away too. Perhaps he was focusing on getting his law degree so that he could yell Ee-yah! in the coaching box and manage the Tigers to pennants ten years later. The 1893 pivot seems irrelevant to Jennings’ profile: he had just over 1000 unimpressive PA before it, and his delayed turnaround seems to have been due to maturing on a terrific team, with a manager he respected in Ned Hanlon. (He replaced McGraw at shortstop, Mugsy moving over to third, and I’ve read accounts that claim that McGraw had a huge influence on Jennings.)

Herman Long (WAR: 37.1; age in 1893: 27; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1889/1903)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….89…..120……106…..…96..…..101……101

ISO… .104… .125….. .098…. .094…. .181….. .130

Jennings was the SS on three pennant winner: the Orioles of ’94-’96; Herman Long bookended that by being the SS on five pennant winners, the Beaneaters of ’91-’93 and ’97-’98. Long is known as an early power hitter: he hit 12 HRs in a season twice, once leading the league (when he retired in 1904, I’d guess his 91 career HRs were a record for shortstops, though I’m not sure). He obviously used ISO power to take advantage of the 1894 hitting surge, but he never exceeded .130 ISO again; he did, however, consistently deliver about 40 XBH per season for the remainder of the decade, while managing only a 98 OPS+ for 1896-99.

Ed McKean (WAR: 38.7; age in 1893: 29; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1887/1899)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…144….109…..…93……119…….118…..125

ISO…. .121… .091… .064…. .163….. .152… .158

McKean was an indifferent defensive SS for the Cleveland Spiders, and we can assume, I think that his value was recognized as laying in his hitting. He conforms perfectly to Doug’s model of a player who responded to the 1893 rules change by going (successfully) for power. His XBH totals for ’90-92 were 36/31/24, and for ’93-’96 they were 57/53/57/48 (all full-time seasons for McKean – his career winds down and then winds up in ’99, even though he was mercifully moved from the Spiders to the St.L Perfectos by the syndicate owners of the two teams). McKean was already in his age 29 season when the pitching distance was changed, and his ability to adjust and exploit the new context seems impressive to me. If he’d been strong defensively and had a little longer career, I think he’d be in the Hall, but his Rfield was -48, and that’s not what you needed at short at a time when fielding miscues and unearned runs were so large a part of the game.

Frank Shugart (WAR: 4.8; age in 1893: 26; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1890/1901)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….47……118…..105..……85..…..89…….82

ISO…. .142… .138… .085..… .075… .144… .110

These years are almost all of Shugart’s MLB career: 1890 was his debut, in the Players League (the year before, he’d been in the Elmira Hottentots outfield). He reappeared in 1897 for 40 games, and then again in 1901 for a more or less full season swan song (he was banned from MLB for punching an umpire severely enough that he was arrested – he was playing for the White Sox in Ban Johnson’s new league . . . bad move); he was active in the Minors in between, and after. He seems to have been a difficult character, and he bounced around a lot in his brief career: eight seasons, six teams. Shugart wasn’t an outstanding fielder, and played quite a bit of outfield as well. His oWAR values reflect this: in 1893, with an OPS+ of 85, Shugart earned 1.1 oWAR; in 1894, he earned only 0.3 oWAR despite having a higher OPS+. The reason seems to be that in ’93 he played two-thirds of his games at SS, while in ’94 he played almost all his games in the outfield.

Germany Smith (WAR: 21.6; age in 1893: 34; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1884/1898)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…43…..…51…..…94……..61..…..66…….87

ISO…. .040…. .059… .097… .084… .112…. .093

Smith was a slick fielder and a slack hitter, but since he was a SS, the former was what determined the success of his career, which lasted fifteen seasons, despite an overall OPS+ of just 75. Smith was one of only four 1890s shortstops to play for an NL pennant winner, which he did in 1890 with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms – look at his OPS+ and ISO figures, and the perceived impact at the time of having a high-Rfield SS (well, of having a slick fielding shortstop) is clear (although Smith, who had moved from the ‘Grooms from the AA to the NL after the 1889 season, was dealt to the Reds – where his fielding numbers get better and better – after the 1890 pennant race). Smith’s record concerning the change in pitching distance was counterintuitive. He had an exceptionally good year in 1892, boosted by 8 HR (twice his next highest total), but when the pitcher was moved back, Smith reverted to form: both his OPS and his ISO fall (that’s OPS, not OPS+). In ’94, he rides the hitting wave in ISO, but doesn’t really change his status relative to league norms: his ISO numbers in ’93-’95 go from 16 points below league average, to 14, to 11. It’s 1896 where Smith seems to have his best year in that regard: his ISO of .105 is eight points above the league – unfortunately, his overall hitting does not match that, and his OPS+ actually declines slightly. After that, he’s done, and out of the Majors after 1898.

……………………

These are the nine regular shortstops who appear in Doug’s study group for the transition from closer to further pitching distance in 1893. Other important shortstops of the 1890s either debuted later than 1892, so they don’t fulfill Doug’s criterion for 1000 PA in the 1890-92 period, for example, Bobby Wallace, who was a rookie in 1894, or they moved to shortstop later, like George Davis, who moved his game up several levels from 1893 on, but initially as a third baseman, not playing at short much till 1896. (Bones Ely is a special case: he debuts in 1884, but doesn’t stick until a decade later, and then becomes a major figure.)

I don’t know whether there’s a real pattern to observe here – shortstop isn’t the position where you’d expect to see the most typical figures for hitting. But I’m thinking of moving on to other positions if I have the energy and anyone seems interested, and perhaps a pattern confirming or complicating Doug’s overall picture will emerge.

Highest OBP with at least 50 SB, since 1901:

.486 / 96 … Cobb

.467 / 83 … Cobb

.467 / 51 … Cobb

.467 / 51 … Sisler

.466 / 67 … Joe Morgan

.464 / 52 … Speaker

.456 / 65 … Cobb

.456 / 61 … Cobb

.452 / 58 … Collins

.452 / 68 … Cobb

.450 / 63 … Collins

Cobb did that in 6 consecutive years.

______

Since 1893:

.547 / 73 … John McGraw

.521 / 100 . Billy Hamilton

.490 / 97 … Billy Hamilton

.486 / 96 … Cobb

.480 / 54 … Billy Hamilton

.478 / 83 … Billy Hamilton

.472 / 70 … Jennings

.469 / 87 … Joe Kelley

Mike L wondered what types of traits characterized the 16 hitters on Doug’s list of those whose ISO declined in 1893-95, over 1890-92. I’ve gone through the list to see what may have cause that decline in the face of a league power surge after the 1893 rules changes. I’m not sure there’s really any dominant pattern, but here’s a closer look at individual cases.

Tom Brown (Position: O; WAR: 16.5; age in 1893: 32; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1882/1897)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…104…..146….…78….….77………80….…63

ISO.… .116… .148… .058..… .083…. .142… .086

Brown, a Liverpudlian, was a long-time itinerant outfielder, whose peak years were actually in the mid-1880s: his OPS+ for his first five seasons (1882-86, but all in the AA) was 135, but he ended up with a career number of 100. He was a low-average, high strikeout player, who had moderate power for his era and very good speed. His best black-ink year was his age 30 season, 1891, when he led the dying American Association in runs, hits, triples, TB, SB, and strikeouts (he was a league leader in Ks five of six seasons starting the 1890s). Brown is a terrific measuring rod for the quality gap between the AA and NL, since he bounced back and forth between them until the AA died, with one year out for the Players league. In the pre-1893 years, Brown played ages 21-25 and 30 in the AA, with a 138 OPS+, and ages 26-28 and 31 in the NL, with an OPS+ of just about 80. Looking at Brown’s performance over the 1892-93 divide, his OPS+ shows no big fluctuation due to the change (his 1890-92 average is puffed up by the context of the PL and AA in ’90-1). His ISO bounces around (there is the same distortion caused by ’90-1), but seems completely uncorrelated with his overall offensive value – the big jump in ’94 exceeds the league’s, but his other batting stats remained static, falling behind in relative terms. (In career terms, Brown’s ISO was simply lower in the NL, .086, than in the AA, .108, and PL .116.) Interestingly, Brown’s ’96-97 performance improved (ages 35-36), his OPS+ rising to 97, due to much higher BA, but his ISO was a bit lower, at .079.

Oyster Burns (Position: O; WAR: 26.1; age in 1893: 28; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1884/1895)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…138….128……159……102……126…….80

ISO… .180… .132…. .138.… .142.…. .146.… .084

Having posted on Burns higher up on this string, I’ll just note again that his ISO “decline” is clearly a product of his outlier years in the talent-thinned 1890 NL on the one hand, and his age-30 MLB swan song in ’95. If we focus on 1891-94, his ISO rises slightly, while his OPS+ suggests an overall decline, relative to the league.

Cupid Childs (Position: 2B; WAR: 44.3; age in 1893: 25; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1890/1901)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…180…..122……150……132….123…….91

ISO… .136… .093.… .081..… .099…. .106… .075

“Cupid” sounds pretty quaint, but it may be better than Clarence Lemuel, which his parents preferred. The figures here are skewed by Childs’ great rookie season, which was with the Syracuse Stars in the talent-thin 1890 AA. Childs moved to the NL Spiders the following season, where he stayed for most of his career, and if we look at his hitting in that more stable environment, he stays consistent (his ’95 season was just an off-year, influenced by a contract dispute that kept him out of the lineup for a while: he bounced back in ’96, and then traces a normal, gradual decline as he ages). Childs’ strategy was lots of singles and lots and lots of walks. His XBH totals from ’91-94 are 35/28/32/35, so the pitching distance change seems to have left him pretty much as he was in terms of power, but his BA rises steadily: .281/.317/.326/.353 (after his off year in ’95, when it was .288, it rebounded to .355 – he was a good hitter, not just an 1894 hitter). Childs really was a terrific player (his Rfield isn’t outstanding, but he had a good contemporary reputation as a fielder), and his short career was probably due to the effects of malaria, which he contracted in 1899 at age 31. Still, Childs’ hitting declines after his age 29 season, and I suspect that this is pretty typical for 19th century players. We’re used to the Bill James idea of age 27 as the peak, but in the 1890s, I think it was more often a bit earlier, with strong seasons after age 30 relatively rare (Cap Anson & Co. notwithstanding).

Lave Cross (Position: C/3B; WAR: 47.2; age in 1893: 27; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1887/1907)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….99…..133……108….…94…..…132…….76

ISO… .131… .157.… .087.… .099.…. .138… .093

Cross was one of those players who leaped on the 1894 hitting boom. His BA of .387 was seventy points higher than any of his other 19th century seasons (his average was .292 over 1887-1900, OPS+ 97). Then, at ages 35-36, he took advantage of another favorable hitting environment, the new AL, to have consecutive seasons of .328 and .342, with identical OPS+ numbers (122). Cross bounced around a lot over his twenty-one year career, usually bouncing back to Philadelphia: he played for Philadelphia teams in four different leagues (AA, PL, AA again, NL, AL). He is – or should be – famous as the player-manager of the early-season 1899 Cleveland Spiders (later the Outcasts), leading them to an 8-30 record before moving over to the sister St.L. team and leaving poor Joe Quinn to take over for the 12-104 remainder. Cross was a regular infielder from 1894 on, ultimately settling in a Third, but he started as a catcher, and spent most of his time there through 1893, though some seasons he played more in the outfield (he was a strong fielder at all positions). This would undoubtedly influence his oWAR ratings, inflating them in his early years, relative to his later ones, though in the ‘90s, the positional adjustment for catcher was only twice the value it was for Third (now it’s 4.5 times). Cross’s ISO spike in 1894 was a product of 51 XBH, but if we look at his profile through the 1890s, his ISO was otherwise not dramatically changed. The reason he seems, despite 1894, to have lost ISO around the 1893 pitching switch is because of his relatively high output in 1891-92, when he was playing, first, for the Players League Philadelphia Athletics, and then for the Philadelphia Athletics in the dying AA. Those seasons were outliers, and if we look at all of 1893-95, his .111 ISO is well above his norm.

Duke Farrell (Position: C; WAR: 23.1; age in 1893: 26; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1888/1904)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….98…..144…..…77……..96….…89….….102

ISO… .113… .171.… .099.… .100…. .146… .119

Farrell was a durable catcher who could handle other positions credibly as well: in 1892, for example, he was an average-fielding regular third baseman, returning behind the plate thereafter (apparently against his wishes, but he was regarded as an outstanding catcher). A look at his ISO numbers above will show that although he’s on Doug’s list of players whose ISO declined after the pitching switch, this is actually an illusion caused by the exceptional numbers he generated in 1891, while playing for the Boston Reds in the dying AA. He adjusted well to the new distance, raising his OPS+ almost twenty points in 1893, compared to his previous year in the NL, and while his ISO was basically unmoved that year, he rode the 1894 wave and powered the ball that year, even though his overall offense fell back a bit against his peers.

Dave Foutz (Position: P/3B/O; WAR: 12.8; age in 1893: 36; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1884/1895)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…132……95.……48………74…..…84….….78

ISO… .130… .092.… .064.…. .110…. .101… .052

Foutz is an unusual name to encounter here, because his major claim to fame is that he is the all-time leader in W-L percentage among pitchers with 200+ decisions (just edging Whitey Ford). I’ve listed Foutz’s WAR totals as a position player, but he has 22.7 pWAR besides. Although he meets Doug’s criterion of 1000 PA in each of the two three-year periods, 1890-92 and 1893-95, he just barely qualifies for the latter, and 1893, his age 36 season, was his last full-time one. Foutz was principally a pitcher from 1884-88, until a hand injury ended his effectiveness, and then again in 1892, and his poor OPS+ and low ISO in ’92 may be connected with his renewed focus on pitching (203 IP). His ISO did initially pick up with the 1893 changes, but in the end age caught up with him. From 1893 through 1896, Foutz’s record was also probably affected by his role as Brooklyn’s player-manager, a job he found difficult. His playing career ended after two games in ’96, his managing career closed when he was fired at season’s end, and Foutz himself was dead before the ’97 season began.

Jack Glasscock (Position: SS; WAR: 62.0; age in 1893: 35; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1879/1895)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…147……86……100…….113..….73…….75

ISO…. .104…. .065… .081..… .092… .081… .057

Since I discussed Glasscock in the post on shortstops I’ll skip him here, except to repeat that his batting decline was likely age-related, rather than an effect of the 1893 pitching switch.

Bill Hallman (Position: 2B; WAR: 7.4; age in 1893: 26; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1889/1903)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….84….105……116….…102….…83….….92

ISO… .093… .111… .090..… .096…. .069… .072

Hallman, like Lave Cross, was a longtime Philadelphia stalwart, playing for Phillie teams in three different leagues. His 1890-91 seasons were with Athletics clubs in the PL and AA, but when he returned to the tougher NL in 1892, he held his own. Never a .300-hitter before 1893, with the new pitching distance he suddenly produced four straight .300 seasons; however, after a slight bump in ISO in ’93, his XBH production declined and he became more and more a Punch-and-Judy hitter. (He was not an outstanding fielder, and these two facets account for his weak WAR rating.) There is nothing in Hallman’s stats that reflects the 1894 hitting surge, and he does, in fact, seem to be exactly the sort of player Doug’s list of ISO-declining hitters was meant to catch: a player who was unable to take advantage of the pitching switch by adjusting to the new power-favorable conditions.

Bug Holliday (Position: O; WAR: 18.4; age in 1893: 26; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1889/1898)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…109.…147……144……118…..125…….90

ISO.… .112… .154… .156.… .118…. .152.… .102

Holliday played his entire, brief career with Cincinnati, coming over from the AA to the NL with them in 1890. He was a little guy, but hit with power, as his ISO numbers for 1891-92 show (he led the NL in HR in ’92 with 13). Although Holliday appears to lose ISO after the pitching switch, that may be a bit misleading. Holliday had terrific years in ’91-92. His ISO drops back to his 1890 level in 1893 (his BA rose significantly, and he led his team), but he was still well ahead of league ISO (.100). Then in 1894, he rides the hitting wave and returns to the level of his best seasons, well above league ISO (.126). His sharp drop in 1895 is not due to any choice to pursue small ball, high average standards rather than the power potential that the new rules had created: Bug had a near lethal case of appendicitis, and the surgery essentially disabled him irreparably. His ’95 season encompassed only 32 games, and he was never a full time player again. Basically, Holliday looks like a player of great gifts but little stamina, who reached his peak at age 25, his subsequent decline being temporarily masked by the offensive environment created by the 1893 changes. In subsequent years, he suffered a series of further health issues and died at age 43.

Denny Lyons (Position: 3B; WAR: 35.5; age in 1893: 27; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1886/1897)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…193….150…..129…….131……113……99

ISO…. .177… .140… .139.… .122…. .132… .091

I wrote about Lyons along with Oyster Burns above – the two players have much in common. Lyons was spectacular as a young player in, ages 21-25, in the AA, with an OPS+ of 161 in those years. but when he joined the NL Giants in 1892, he fell to earth. In ’93, his mild decline in ISO seems a bit misleading. He had about thirty percent more PA (145 more), and he got a lot out of them, increasing his hits by 50, doubles by three, triples by nine, and walks by 38; although he hit five fewer HR, his runs scored rose from 71 to 103, and he more than doubled his RBI, to 105 from 51. Basically, his XBH rate stays constant, but the distribution was slightly less favorable. Then, after 1893, his game dissolves: those figures for ’94-95 are for part-time play – even so, in a half-season in ’94, he exceeded his ’93 HR count (he played McAleer’s only 34 games in ’95). After a brief revival in ’96, Lyons is done after a quarter-season in ’97. His ISO decline from ’90-92 to ’93-95 seems to be part of an overall early-age decline, compounded by a switch from the AA to the NL, and the pitching transition of 1893 doesn’t in itself seem to have affected his ISO in a significant way.

Jimmy McAleer (Position: O; WAR: 1.5; age in 1893: 28; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1889/1898)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+….88……78…..…92…..….54…..…69…..….62

ISO… .073… .073… .091.… .037….. .091.… .043

McAleer’s hitting was so anemic that it’s hard to understand how he could remain in the lineup for Cleveland teams for ten years. His value, it seems, was his recognized fielding excellence, and Rfield does indeed rate him well. However, because he was an outfielder advanced stats don’t agree with contemporary assessments that his prowess in the field was worth his weakness as a hitter, and is essentially pegged as a replacement-value player. McAleer’s best season was 1892 – although his .238 BA would not have impressed anyone at the time – but for some reason his playing time was sharply curtailed over the following two seasons: essentially he became a half-time player. The awful level of his ’93 play suggests an injury was the cause, since we might expect that if he was healthy, the Spiders would have released him then and there. He did return to full-time play in ’95, and ’96 turned out to be his best season in years (OPS+: 83, but an ISO level of only .059). In his final full-time season, extra-bases hits simply disappeared: his ISO over 424 PA in 1898 was .008 (not a typo). So McAleer seems to qualify as a player who was simply unable to profit from the ’93 pitching switch – as if he used up all his power in 1892, his age 27 season, when he managed 37 XBH (he hit only 72 more over the remaining 2306 PA of his career – hard to figure for a guy who was six feet tall and 180 pounds: big for the era). I was much surprised to see what a dismal hitter McAleer was because his name is a familiar one and I’d thought of him as prominent. It turns out his prominence was all as a baseball manager and executive, and it was in that context that I’d come to recognize his name. When I looked to his SABR bio to find reasons for his frequent benching, I found that although the bio ran to over 2600 words, his MLB playing career was covered in only about 160 of them.

Bid McPhee (Position: 2B; WAR: 52.6; age in 1893: 33; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1882/1899)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…116….109…..126….…106……104…….110

ISO…. .131… .114… .096.… .098…. .116….. .118

McPhee spent his entire 18-year career as second baseman for the Cincinnati Red Stockings / Reds; like Bug Holliday, he moved with them from the AA to the NL in 1890. He’s in the Hall with a reputation as the finest second baseman of the 19th century. McPhee’s apparent ISO decline in ’93-95 seems illusory: his fine record in 1890, when the NL talent pool was thinned by the PL challenge, distorts the stats. McPhee’s post-1892 ISO is .101, precisely the level he had maintained up to that tie, despite the fact that he continued to play through his age 39 season. Although he more or less runs out of HRs after 1894, his XBH totals remain near career norms, and given that McPhee was so outstanding defensively, the Reds were not giving up anything in playing a 102 OPS+ second baseman over the 1893-99 period (even at age 39, McPhee is calculated as generating positive dWAR). It’s true that McPhee did not take much advantage of the new pitching distance, although his averages rose to some degree. However, given his age in 1893, this may have been a reflection of a natural decline in his hitting skills, masked by the change in the offensive environment, rather than any mismatch of natural skills to the new arrangement, or any purposeful commitment to “small ball” in a context that rewarded power.

Jimmy Ryan (Position: O; WAR: 43.3; age in 1893: 30; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1886/1903)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…130… 125…..152……119….113……110

ISO…. .123… .156… .145.… .129…. .124… .128

Ryan was a mainstay on Cap Anson’s Chicago team from his debut until the end of the century, with a year off, defecting to the PL Chicago Pirates. His peak years were his age 25 and 26 seasons (1888-89), where his ISO was .188 (he hit 33 HR over those two seasons, averaging over 60 XBH). As an established power-hitting regular, he was able to keep his position through a long period of gradual decline as he aged, punctuated with two fine returns to form, in his age 35 season (143 OPS+) and during a two-year AL extension of his career in 1902-3 (after a season in the Minors in 1901), when he posted a 130 OPS+ stat in ’02. Ryan’s surprising drop-off in 1893 coincides with his only season after 1886 with under 100 games, and may well be a function of injury. He bounced back in 1894 with a .357 BA, but his power never really returned: after 69 HR in six seasons through 1892, he hit only 45 over the next ten. So it seems likely that the ISO drop that lands Ryan on Doug’s list was primarily a matter of aging.

Billy Shindle (Position: 3B; WAR: 17.5; age in 1893: 32; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1888/1898)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…124…..53…..…96…..….86…..…86….….89

ISO.… .159… .036… .105.… .090…. .108.… .071

Shindle was a mediocre hitter, given that he was just an adequate fielding third baseman; apparently his fielding skills were judged more favorably by contemporaries than by advanced stats. He was traded to Brooklyn from Baltimore before the ’94 season, making way for McGraw to move to Third and Jennings to take over SS: probably a key factor in the Orioles’s emergence as a super team. Shindle got started late in professional ball, and didn’t have a full season in the Majors till he was 27. His peak years were ages 28 and 29 — the latter one, in the PL in ’90, shows up in Doug’s calculations and somewhat skews the before/after contrast around 1893. On the other hand, Shindle crashed so badly in the following season that it almost balances out. That 1891 season has his lowest game total after becoming a regular, and it may be that an injury accounts for the low stats, though it could equally be that the stats account for the low game total. In any event, the 1890 ISO figure is 50 points higher than any other Shindle season and 70 points above his career average. When that PL outlier figure is eliminated, the pre-’93 and post-’93 Shindles look very much alike, with the latter actually being somewhat stronger inn power numbers, probably reflecting the change in environment, muted by age decline (I’m looking now at Shindle’s age 32-36 seasons; at age 37 his power dropped off a cliff and his career followed).

Mike Tiernan (Position: O; WAR: 42.2; age in 1893: 26; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1887/1899)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…160…163……135….132….…89.….147

ISO… .192… .188… .113… .166… .142… .181

Tirnan was ensconced in right field for the Giants from his rookie year to his retirement. He had his peak seasons in 1890 and 1891, when he was only ages 23-24; he led the league in HR both years. He tailed off in ’92, but in ’93 he rebounded – however, given the changed pitching context, he was actually only keeping stead, as his OPS+ barely moved, depite his OPS jumping 100 points. He missed out on the ’94 hitting surge – his SABR bio notes that the reason is a mystery, as he had no reported injury – but then he surged back during the following two years. Although Tiernan’s OPS+ in ’94 was poor, his style of play remained power hitting, and his ISO remained pretty stable. The only reason he’s on Doug’s list is really the fact that his peak years occurred during the ’90-92 period and he had an anomalous season in ’94. From ’95-97, Tiernan returns to a norm of 44-51 XBH per year. His game weakens in ’98, and he’s out of the Majors after 35 games in 1899.

George Van Haltren (Position: O; WAR: 39.9; age in 1893: 27; first/last seasons, 100PA: 1887/1903)

…….…1890….1891….1892….1893….1894….1895

OPS+…121…..140…..133……128….100…….136

ISO…. .109… .125…. .116.… .085…. .097… .163

Van Haltren bounced around early in his career, and then wound up in center field, next to Mike Tiernan, from 1894 through the end of the century. He was a leadoff hitter, and above average in walks and SB, though his figures in each category were not eye catching (however, he did lead the 1900 NL in SB at age 34). When the 1893 changes occurred, Van Haltren’s BA had just slipped below .300 for the first time, and it may be that his reduced power in ‘93 reflected a focused effort to prove to a new team (Pittsburgh – he’d actually finished ’92 with them, and been terrible, with a .200 BA) that he had the ability to get on base that a leadoff man requires. He did boost his average to .338, but, of course, the whole league was hitting, and in ’94 he didn’t ride the crest of the power surge, although he drove in a very high number of runs (105) for his new team, the Giants, who he remained with for the final ten years of his career. Obviously, Van Haltren was able to boost his power level in 1895 by such a large amount that he barely qualifies for Doug’s chart, that season almost compensating for the two before. 1896 was also a good ISO year for Van Haltren (.133), although he falls back afterward, as his triples and HRs begin to wane after age 30. In this respect, if the ’93 pitching switch opened the way for power hitters, Van Haltren didn’t so much resist as he was slow to join in.

Spectacular work, EPM. Deserves a post all on its own.

Too bad so few people are reading them.

Well, you two are, and I appreciate the comments!

Yes, EPM, well done! Great descriptions and analysis. Thank you for the work

Years ago I read “The Beer and Whiskey League” about the AA. This is about all I’ve ever read specific to 19th century baseball. And, honestly, I can’t recall a darned thing from the book except Pete Browning being characterized as a heavy drinker. Visually, all we have of the era are colorized photos and we are at the mercy of anecdotal stories told by hometown sportswriters.

I did enjoy, “The Glory of Their Times” with the old guys telling their stories

epm: Just to clarify, I do not mean to imply there are too few current readers and commenters on this site who are not reading your comments. I am alluding to the fact that there are too few people overall who access the HHS web site. I logon to Twitter regularly, following mostly baseball fans, and your and Doug’s comments and articles are superior to their comments (except Andy’s, of course).

Bug Holliday, if he’s remembered at all, is likely remembered for debuting in the postseason. He was only 18, and IIRC Cap Anson basically picked him off the sandlots to fill in for an injured player.

Four years later he re-debuted with the Reds and had a nice little career.

Lave Cross played for three teams called the Philadelphia Athletics in three different leagues. He played for a 4th Philly team in yet another league. I believe he may be the only player that can claim that.

Since 1901 Lave Cross holds the record for most RBI with 0 HR. In 1902 he had 108 RBI and 0 HR.

At retirement in 1907, Cross was 5th all-time in career hits. I imagine if there was a Hall of Fame in 1920, he might have made it?

Spectacular stuff, epm.

Better write-ups on these players than you`ll find in many of the tomes written expressly for 19th century baseball.

Many thanks, Doug. With your new post, it’s time to move back to the present, but I hope there may be more chances over the coming months to revisit the 1890s.

I was thinking, for example, of posting a comment about the old Baltimore Orioles, and the enormous impact that distinctive and innovative team had on 20th century MLB history. It’s the source of a managerial lineage that moves through McGraw to Stengel to Martin, and the style of play — restrained by rules to curb its rowdiness — did much to shape the following two decades. And the Orioles are just one of several franchises in the 12-team NL that seem ancestral to later aspects of the game. I think it’s a terrific baseball decade.

Sounds fantastic. If you write it (perhaps in a series), I’ll post it. My e-mail is on the About page.

I’ll work on something about the Orioles that can be a change of pace after the first phase of the new season, and some follow-up ideas if there seems to be interest.

Pingback: The Old Baltimore Orioles and the Transformation to Modern Baseball |