This post is for voting and discussion in the 129th round of balloting for the Circle of Greats (COG). This is the first of four rounds of balloting adding to the list of candidates eligible to receive your votes those players born in 1974. Rules and lists are after the jump.

The new group of 1974-born players, in order to join the eligible list, must, as usual, have played at least 10 seasons in the major leagues or generated at least 20 Wins Above Replacement (“WAR”, as calculated by baseball-reference.com, and for this purpose meaning 20 total WAR for everyday players and 20 pitching WAR for pitchers). This first group of 1974-born candidates, including those with A-C surnames, joins the eligible holdovers from previous rounds to comprise the full list of players eligible to appear on your ballots.

In addition to voting for COG election among players on the main ballot, there will be also be voting for elevation to the main ballot among players on the secondary ballot. For both ballots, which may be voted at the same time or in separate posts, voters must include three and only three eligible players. For the main ballot election, the one player who appears on the most ballots cast in the round is inducted into the Circle of Greats, while for the secondary ballot election, the one player appearing on the most ballots cast is elevated to the main ballot for the next COG election round. In the case of ties, a runoff election round will be held for COG election, while a tie-breaking process will be followed to determine the secondary ballot winner.

Players who fail to win either ballot but appear on half or more of the ballots that are cast win four added future rounds of ballot eligibility. Players who appear on 25% or more of the ballots cast, but less than 50%, earn two added future rounds of ballot eligibility. One additional round of eligibility is earned by any player who appears on at least 10% of the ballots cast or, for the main ballot only, any player finishing in the top 9 (including ties) in ballot appearances. Holdover candidates on the main ballot who exhaust their eligibility will drop to the secondary ballot for the next COG election round, as will first time main ballot candidates who attract one or more votes but do not earn additional main ballot eligibility. Secondary ballot candidates who exhaust their eligibility will drop from that ballot, but will become eligible for possible reinstatement in a future Redemption round election.

All voting for this round closes at 11:59 PM EST Thursday, January 31st, while changes to previously cast ballots are allowed until 11:59 PM EST Tuesday, January 29th.

If you’d like to follow the vote tally, and/or check to make sure I’ve recorded your vote correctly, you can see my ballot-counting spreadsheet for this round here: COG 1974 Part 1 Vote Tally. I’ll be updating the spreadsheet periodically with the latest votes. Initially, there is a row in the spreadsheet for every voter who has cast a ballot in any of the past rounds, but new voters are entirely welcome — new voters will be added to the spreadsheet as their ballots are submitted. Also initially, there is a column for each of the holdover candidates; additional player columns from the new born-in-1974 group will be added to the spreadsheet as votes are cast for them.

Choose your three players from the lists below of eligible players. The current holdovers are listed in order of the number of future rounds (including this one) through which they are assured eligibility, and alphabetically when the future eligibility number is the same. The 1974 birth-year players are listed below in order of the number of seasons each played in the majors, and alphabetically among players with the same number of seasons played.

Holdovers:

| MAIN BALLOT | ELIGIBILITY | SECONDARY BALLOT | ELIGIBILITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kevin Brown | 11 rounds | Andre Dawson | 10 rounds |

| Luis Tiant | 8 rounds | Ted Lyons | 4 rounds |

| Dick Allen | 5 rounds | Rick Reuschel | 4 rounds |

| Bill Dahlen | 5 rounds | Willie Randoph | 3 rounds |

| Manny Ramirez | 5 rounds | Todd Helton | 3 rounds |

| Graig Nettles | 3 rounds | Andy Pettitte | this round ONLY |

| Bobby Wallace | 3 rounds | ||

| Richie Ashburn | 2 rounds | ||

| Dwight Evans | 2 rounds | ||

| Ken Boyer | this round ONLY | ||

| Ted Simmons | this round ONLY | ||

| Don Sutton | this round ONLY |

Everyday Players (born in 1974, ten or more seasons played in the major leagues or at least 20 WAR, A-C surname):

Bobby Abreu

Miguel Cairo

Orlando Cabrera

Frank Catalanotto

Jamey Carroll

Marlon Anderson

Sean Casey

Jose Cruz

Roger Cedeno

Mark Bellhorn

Emil Brown

Pitchers (born in 1974, ten or more seasons played in the major leagues or at least 20 WAR, A-C surname):

Chad Bradford

As is our custom with first time candidates, here is a factoid and related quiz question on each of the new players on the ballot.

- Bobby Abreu recorded thirteen straight seasons (1998-2010) playing 150 or more games, tied with Willie Mays (1954-66) for the longest such streak in majors history. Excepting strike-shortened campaigns, which three players have longer streaks of such seasons? (Pete Rose, Cal Ripken, Rafael Palmeiro)

- Miguel Cairo played in 29 post-season games, but never in the World Series. Which player has appeared in the most post-season games without playing in the World Series? (Russell Martin)

- Orlando Cabrera is one of

threefive players with 600 games at shortstop in each league. Who are the othertwofour? (Monte Cross, George Davis, Leo Cardenas, Royce Clayton) - Frank Catalanotto topped 100 OPS+ and 15 oWAR for his career. Among such players with careers starting in 1995 or later, which retired outfielder hit fewer home runs than Catalanotto’s total of 84? (Angel Pagan)

- Jamey Carroll played over 250 games at 2B, SS and 3B. Who was the first expansion era player with such a career? (Tony Phillips)

- Chad Bradford recorded a 0.39 ERA for his post-season career. Who is the only pitcher with a lower career ERA in 20+ post-season games? (John Rocker)

- Marlon Anderson’s 7 home runs for the Dodgers are tied for the most by any player with fewer than 50 games for LA. Who was the first player with this achievement? (Steve Bilko)

- Jose Cruz’s .198 career ISO is fifth highest in a 5000 PA career with OPS+ under 105. Which player with OPS+ under 105 as a Blue Jay has the only ISO higher than Cruz’s in 2500 PA in Toronto? (Joe Carter)

- Sean Casey’s 197 hits in 1999 are the most by a Reds first baseman in the post-war era. Which post-war era Reds first baseman recorded a season leading the NL in hits? (Ted Kluszewski, 1955)

- Roger Cedeno’s age 24 season for the 1999 Mets featured a .300 BA, 60 steals and 60 walks. Which other NL player posted these totals at as young an age and, like Cedeno, did not lead his league in steals? (John McGraw, 1894-95)

- Mark Bellhorn‘s best season came in 2002 for the Cubs with 27 HR and an .886 OPS, but only 56 RBI. Who is the only Cub to post a higher OPS and fewer RBI in a 400 PA season? (Topsy Hartsel, 1901)

- Emil Brown logged 600 PA and stroked 150 hits in consecutive seasons (2005-06) aged 30-31, the oldest player to do so in his first two years in Kansas City. Who is the youngest player to post these totals in his first two seasons as a Royal? (Amos Otis)

8. This is definitely HHS favorite Joe Carter.

The answer to the first question must be Rose and Ripken.

Not sure why I wrote two, but there are actually three players, those two and one more.

Lower the threshold to 146 games and Ichiro joins them at 13 seasons. I haven’t the foggiest who the third player would be.

Lou Gehrig makes 13 seasons at 149 games, dipping that one game below 150 just once.

Rafael Palmeiro?

That’s it.

Is #4 Denard Span, or are we assuming he gets a job this summer?

Not Span, who hasn’t retired (yet).

9. Definitely Ted Kluszewski, 1955.

For several years I’ve been posting a table of certain stats for all the CoG candidates I regard as viable. The key figures include:

Total WAR

Peak 5-yr WAR

Best 5 yrs for WAR

WAR/G or WAR/9IP

WAR/yr (with certain minimal criteria for a season to count)

OPS+/ERA+

Career length, with the shortest career among the candidates (hitters & pitchers separate) the reference point at 1.0.

I don’t know if anyone pays the least attention to these tables. Obviously, they present an incomplete picture because they are so reliant on WAR, an imperfect measure. But I’m posting them again, mostly as a celebratoy affirmation of obsessive personality disorder.

This round, the only new, 1974-birthdate candidate I see as viable for the list is Bobby Abreu. The rest are holdovers.

Main Ballot Candidates

Pitchers

P(Tot)WAR…Peak5..Top5…WAR/9IP…WAR/Yr….ERA+…Career length

68.5 (68.3)……37.0…37.0……0.189……4.0 (17)……127……1.0………K. Brown

66.1 (66.7)……28.7…34.7……0.171……3.9 (17)……114……1.2………Tiant

68.7 (67.4)……22.5…27.3……0.117……3.0 (23)……108……1.6………Sutton

Position Players

WAR……Pk5……Top5……WAR/G…WAR/Yr……OPS+…Career length

60.0………29.7……31.1……0.025……3.8 (16)…..128………1.4……….Abreu

58.7………31.5……36.7……0.034……4.2 (14)……156………1.0………Allen

63.6………31.6……32.7……0.029……4.2 (15)……111………1.3………Ashburn

62.8………33.0……34.0……0.031……4.5 (14)……116………1.2………Boyer

75.2………22.6……29.8……0.031……4.0 (19)……110………1.4………Dahlen

66.9………23.7……28.3……0.026……3.5 (19)……127………1.4………Evans

68.0………28.7……32.2……0.025……3.4 (20)……110………1.4………Nettles

69.2………28.7……29.9……0.030……4.1 (17)……154………1.3………Ramirez

50.1………23.3……26.4……0.024……2.6 (19)……118………1.4………Simmons

70.2………28.6……31.3……0.029……4.2 (17)……105………1.3………Wallace*

* Wallace’s total WAR (incl. pitching) is 76.3.

WAR/Yr. includes only those seasons with 10 GS or 100 IP for starters, 20G for relievers, and 50G for position players.

Career length: 1.0 = K. Brown 3256.1 IP / Allen 7315 PA.

Secondary Ballot Candidates

Pitchers

P(Tot)WAR…Peak5..Top5…WAR/9IP…WAR/Yr….ERA+…Career length

67.2 (71.6)……24.2…29.0……0.145……3.6 (19)……118……1.6……….Lyons

60.9 (60.8)……20.3…28.4……0.166……3.4 (18)……117……1.0……….Pettitte

68.2 (70.1)……31.0…32.8……0.173……4.0 (17)……114……1.4……….Reuschel

Position Players

WAR……….Pk5……Top5……WAR/G…WAR/Yr……OPS+…Career length

64.4………32.4……33.7……0.025……3.4 (19)……119………1.5………..Dawson

61.4………37.4……37.4……0.027……3.8 (16)……133………1.3………..Helton

65.5………27.2……29.5……0.030……3.7 (18)……104………1.3………..Randolph

If you ranked the main ballot position players, 1-10, for each category and added them up, F W I W, it would look like:

27 Allen

28 Boyer

31 Ashburn

32 Manny

37 Nettles

37 Abreu

38 Wallace

42 Evans

55 Simmons

Whether or not this is relevant from a “logic” standpoint is anybody’s guess. If you asked me (and no one is asking), I’d go with oWAR and/or rBAT as some sort of tie-breaker in any discussion on the merits of any of these players. But, again, no one asked

An awfully odd approach, Paul. By the way, Dahlen would be at 36, but I have no idea what that means.

I think rBAT or oWAR make sense for outfielders and first basemen, whose defensive contributions lie in a narrow range, and who are expected to produce most of their value at bat. For the keystone infielders and catchers, I don’t think they are a fair measure, since they are expected to produce much more value in the field. Third basemen, it seems to me, vary by era on that score. In theory, oWAR and dWAR are on the same scale; the difference is the reliability of the stats, but that doesn’t mean dWAR is worth less than oWAR. Shaky defensive stats are as likely to undervalue as overvalue a fielder’s contributions.

My vote.

Main: Tiant, Evans, Wallace

Secondary: Dawson, Reuschel, Randolph

Dept. of Shameless Self-Promotion

Last spring, I wrote a series of posts for HHS devoted to baseball in the 1890s, which I regard as the point where the sport exits its early phase and enters its “modern” one (for reasons I explain ad nauseum in the posts). One of my goals in writing those posts was to create some interest in the era during which two of our CoG candidates played significant portions of their careers: Bill Dahlen and Bobby Wallace. My thinking was that those two players, who are the WAR leaders among current candidates, lose support because, although they fully qualify for the CoG under the birtlecom rules — both earned the requisite amount of WAR after 1900 — their 1890s performances are discounted as not relevant to baseball-as-we-know-it.

I think the top players of the 1890s — especially the ones that continued playing through the transition to the two-league structure of the 20th century — created baseball-as-we-know-it, and deserve, if anything, more, not less, credit for the roles they played when they played them. Although my posts deal with the era of the 1890s generally (and especially changes associated with the rise of the Old Baltimore Orioles), rather than with those two players, I hoped they might help create a context that helped Dahlen and Wallace seem as relevant to the CoG as later, more familiar players.

So in case anyone who hasn’t looked at those posts may be interested in them, I thought I’d add links to the three parts, which I’m nicknaming Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

I expect that in subsequent comments I’ll say more about Dahlen and Wallace specifically. If I become a bore on the subject, feel free to let me know. I won’t be offended; I’m used to it.

One of the quiz answers features prominently in your series.

Indeed. But I’m so hopeless at your quizzes that I didn’t see it before your hint.

Wallace’s stats are so unimpressive it’s hard for me to understand how he accumulated so much WAR.

I’m going to go read your Part 1 through 3 articles in hopes of understanding. But maybe you have an explanation?

The most relevant data would be in Part 3, Joseph, where fielding is a topic, but I don’t deal with Wallace individually.

The period of Wallace’s career saw a dramatic change in fielding standards, and Wallace was a leader of that change. This was a time of very low TTO play: in baseball before Wallace’s career period fielders allowed many more batters to reach base and there was about a 7% likelihood that a chance would lead to an error (by the end of Wallace’s career that figure would be about 4%, an enormous change). Wallace was famous for realizing that infield hits could be turned into outs if the fielder’s throw could be accelerated, and he solved that problem by developing a seamless motion that eliminated the stop-and-set moment from the fielding/throwing process on routine plays, resulting in an improved out rate and thus higher “Range” stats. I can’t really describe the change well because, although baseball histories describe it, it became universal by the end of Wallace’s career and we’ve always seen that sort of fluidity in Major League players. But Wallace’s sure hands and innovative mechanics are behind his high dWAR figures.

On offense, Wallace’s 105 OPS+ seems unimpressive, especially when you compare him with Wagner. But compared with other shortstops, he looks very good. Here are the MLB shortstops, 1901-10, who played at least 800 games, sorted by OPS+:

Wagner 171

George Davis 113

Wallace 111

Kid Elberfeld 106

Freddy Parent 99

Dahlen 96

Terry Turner 95

Joe Tinker 93

Mickey Doolin 82

Monte Cross 70

Tommy Corcoran 67

Take away Superman, and Wallace is on a par with Davis, a CoG member, for the lead. A guy who could bat above average and handle the key infield slot with high skill was (and still is) a precious commodity. (Take away Lajoie too and Wallace will be competitive with all other middle infielders and third basemen.)

You can find a comparable example in Brooks Robinson. His OPS+ is actually a notch lower than Wallace, at 104, but he’s an easy Hall of Famer and CoG member because his innovative work at 3B created exceptional dWAR to supplement his average hitting. Clete Boyer, a Robinson contemporary who was about equally skilled at Third, would have accumulated about as much dWAR in a comparable career, but he wasn’t able to do that because his 86 OPS+ limited his total value.

Thanks for the extensive reply. Makes sense.

2: Russel Martin 57 games

3: Royce Clayton, Monte Cross, Leo Cardenas, George Davis (hmm 4 players?!?)

Main Ballot Vote: Manny Ramirez, Luis Tiant, Kevin Brown

Secondary Ballot Vote: Andy Pettitte, Todd Helton, Andre Dawson

I hadn’t considered 19th century players, but thanks for pointing out Cross and Davis.

4: Angel Pagan hit 64 HR with an OPS+ of 102 and 18.6 oWAR

5; Tony Phillips

7: Steve Bilko in 1958

10: George Burns 1914 (was only third)

John McGraw 1894 (second) and 1895 (third)

It’s McGraw. Burns led the NL with 62 steals in 1914.

11: Topsy Hartsel in 1901 with OPS of .886 and 54 RBI

12: George Brett in his age 22 and 23 seasons

Those were not Brett’s first two seasons as a Royal.

Kevin Seitzer at ages 25 – 26? He did appear in less games than the random RoY limits (in a cup of coffee at age 24) to the extent his second season merited a 2nd place finish in the RoY award voting

How about Amos Otis?

It is Otis.

Emil Brown (who I have absolutely no recollection of) batted .200 in fewer than 500 PA over 5 seasons through age 26, then played only in the minors for 3 years (for four organizations), before landing in KC at age 30 and becoming their regular right-fielder for two seasons, Not your typical road to becoming an everyday player.

Brown was effective at the plate for those seasons, but brutal in the field, turning in the second lowest season Rfield score by a Royal outfielder, ahead of only iron-gloved Danny Tartabull (Kauffman Stadium is not a forgiving ballpark for weak corner outfielders, yet the Royals kept Tartabull out there for 5 years and -64 Rfield).

In looking at Otis’ career, it’s almost shocking how well he fielded in 1978 (+16 runs) compared to the rest of his career (-50 , without a season half as good as 1978). Strangely enough, he also accumulated the most rBat in that season as well with a career high OPS+ of 151.

Hit the cover off the ball in the 1980 WS and followed it up with an 0 for 12 in 1981 playoffs

It always felt like the Indians and Royals played each other about 50 times a year in the 00’s, so I do remember Emil Brown. He was indeed just as atrocious in the field as his Rfield would suggest.

I remember Brown with the Pirates. Shows the merits of second chances…after three years in the minors (ages 27-29), at ages 30-31, he plays everyday for the Royals AAAa team in Kansas City. They managed to lose over 200 games for the years in question (2005-’06). Alas, it looks like they’re doing their level-headed worst to duplicate that type of performance

My ballot is below.

I’ve decided to put in a little bit of work that I haven’t done in a few years. I have always included a (peak-weighted) modified version of Baseball-Reference WAR to determine my votes (with some extra credit given for catchers, as well as the logical considerations of wartime service, racial segregation, etc.). I’ve long thought that I should include Fangraphs’ WAR in my considerations. You might think, “That only matters for pitchers,” but that’s just not true. Sure, Bobby Abreu (60.3, 59.6) looks the same by either measure. But that’s not everybody. Here are three non-pitchers on the ballot right now, bWAR first, fWAR next:

Ken Boyer: 62.8, 54.7

Richie Ashburn: 63.5, 57.6

Ted Simmons: 50.2, 64.9

Uh… those are pretty different. And that doesn’t even count how different the pitchers can look extremely different, as we all know. Here are all three pitchers on the main ballot:

Don Sutton: 68.9, 85.6

Luis Tiant: 65.9, 54.7

Kevin Brown: 68.7, 76.4

So… were these three pitchers all worth roughly the same amount over the course of their career, per Baseball-Reference, or are these three very easy to stratify in terms of career value, a la Fangraphs? I think that, probably, the best thing to do is average the two. Pitchers do not have total control over balls in play; this is absolutely and undeniably true. On the other hand, there is sometimes consistency in batted-ball results, and better pitchers tend to get better batted-ball results than really bad pitchers – plus, it happened, so we should account for it. Fine. So, henceforth, I’m averaging the two. That, for me as a LONG-time Tiant supporter, means that he’s finally losing my support (it’s basically impossible to vote for him given this result.

I will continue not to vote for 19th-century guys, because I don’t believe they were really playing Major League Baseball. Even in the late-1890s, I think it’s unclear that the level of competition was that great. This makes Dahlen and Wallace mildly interesting as candidates, but I don’t plan to vote for them. So here’s my new list:

Kevin Brown

Dick Allen

Graig Nettles

And for the secondary ballot… well, I don’t think any of these guys are electable here in 2019, but here goes:

Rick Reuschel

Todd Helton

Andre Dawson

I will likely make my annual plea for Kevin Brown later, and I may put out some thoughts on the others. But for now, I’ll wait to see other discussion and just post my initial ballot – though I am not unwilling to be convinced to change my ballot before Tuesday if someone can really convince me.

Since I’m playing the role of 1890s-defender, I want to respond to Doom’s comment: “. . . I don’t believe they were really playing Major League Baseball. Even in the late-1890s, I think it’s unclear that the level of competition was that great.” (I originally wrote, “respond briefly,” but when the data changes, I change my mind!)

To take the last part first, level of competition generally rises throughout MLB history. The CoG rules, which try to replicate the psychology of the early BBWAA voters, rather than the rules, assume that there is some significant feature to the year 1901, such that WAR accumulated from 1901 on count towards eligibility and WAR accumulated previously does not. The idea (as I recall it) was that, except for Cy Young and Willie Keeler, the early BBWAA voters acted as though this were a rule, and left earlier players to the Veterans Committee. A secondary function of this was that most BBWAA voters probably knew very little about pre-1901 baseball, because they were too young to recall it, and research tools were inadequate to inform them meaningfully about it. (This was not true of all voters, and some did vote for 19th century players.) Since the CoG was conceived as a project to do the BBWAA project over, and do it better than the BBWAA did, it has never been clear to me why the arbitrary line of 1901, which was, in large part, an informal product of ignorance and laziness, was elevated to a rule.

So the reasons BBWAA voters acted this way was most likely not because of judgments about the level of competition prior to 1901; it was because “baseball as we know it” meant for most of them the two-league structure that began in 1901. That structure, in itself, has little or nothing to do with the nature of the game. Levels of play and of the standard of competitive skill have, by and large, been in a continuous state of improvement since 1876. (The major break in the curve would correspond to the rise in skill levels over the period 1947 to the early 1960s, associated with the integration of baseball and the new pool of formerly excluded black players — a point often made by mosc.) The level of competition in 1965 is clearly far superior to the level of 1905, or 1915, or 1925; yet we treat those earlier eras on the same terms as the later one because player quality has to be assessed in terms of evolving contemporary standards — other wise we’d probably have only a handful of CoG members before the period of integration. In terms of competitiveness, it is very likely the case that there was a drop in competitive levels precisely in 1901, when, after eight years of twelve MLB teams, followed by one year of only eight, MLB suddenly had to fill 16 teams. So in terms of quality of play, 1901 might be the worst year to choose as the start of high-quality ball.

If we could go back to the dawn of the CoG, I’d argue to birtelcom that we should not adopt the arbitrary line that BBWAA did, but should figure out whether we should treat 1876 on as a single continuum, or whether there was, in fact, a true dividing line between “baseball as we know it” and an earlier phase of MLB baseball evolving towards, but not yet, the game we know. I wouldn’t have known it then, but I now believe that the line is quite clear, and that it should be drawn at 1893, for multiple reasons. (No point in reiterating all that here, but the game of the mid- and late 1890s was simply sharply different from the game of the 1880s, and very much consistent with the game of the 1900s.)

Now there’s not a lot of time between 1893 and 1901, but those years are critical to the candidacies of Wallace and Dahlen: they are the two players who have actually been impacted by the fact that, although the CoG rules don’t preclude our considering their play in the 1890s, the way the rules are stated may make it seem as if those years should not be counted. In other words, I think we are replicating the informal error of the BBWAA voters’ psychology when we have all the data necessary to correct the false premise that most of us grew up with: that “modern” baseball suddenly starts in 1901.

I mean, we’ve had this discussion before. But let’s have it again; it’s a fun one.

1. There was no “rule” about pre-1901 balloting. I (and some others) have chosen not to vote for pre-1901 players, partly because we were reliving the BBWAA. They didn’t consider those guys, because that was “a different game.” They had an expert committee. If I can vote for those players, I probably should’ve been writing in Josh Gibson and Bullet Joe Rogan for a LONG time, since A.) I’m sure that the Negro Leagues of the ’30s and ’40s were of higher quality than the 19th century NL, and B.) those players dominated their opponents to a similar or greater extent than Dahlen and Wallace. However, we don’t consider Negro League players, because the BBWAA didn’t consider Negro League players. Likewise, I’ve taken the approach that, if the BBWAA didn’t consider those 19th century guys, the COG becomes less an exercise in re-litigating the BBWAA process, and more an exercise in jst doing whatever we feel like. I realize it’s still not perfect (after all, Ichiro’s been in the COG for a while, and he’s still and active major leaguer), but I’d still like to keep up the fiction that we’re doing the right thing by mimicking the BBWAA.

2. 1901 is certainly NOT the worst year one could pick. First of all, while the AL’s level of competitive balance was all out of whack in 1901, by 1903 at the latest it was on par with the NL. And the NL, while it lost Nap Lajoie, was basically the same league in 1901 that it had been in 1900. In modern baseball, it takes a few years to recover from expansion, because, for a while, the talent pool doesn’t expand, but the number of league players does. That is simply untrue of the 1901 AL. They were taking from a totally separate pool of players, and those players were just as good as the NL players. This is because NL scouting was not remotely like it is now; teams were filled with locals; there were virtually no players from the West or Southeast. It was just a shallow pool. The introduction of the AL EXPANDED the talent, rather than dispersed it, as other rounds of expansion have done. Bill James has written about this extensively.

3.) 1893 would be an okay dividing point, if it weren’t for a couple of things that make 1890s baseball look… bush league. Here are some facts about 1890s baseball:

A. Teams did not play balanced home-road schedules. The 1898 Cleveland Spiders, for example, played 57 home games and 92 road games.

B. Rosters and their rules were not settled. Into the 1890s, there are stories of fans being called out of the stands to play in major league games. That does not sound like major league baseball. It sounds like what I had hoped would happen when I wore my little league uniform to an MLB game when I was 7.

C. Teams didn’t have consistent fields or nicknames. Again, the 1898 Cleveland team had SEVEN home ballparks… and they weren’t all in Cleveland.

D. Cleveland. In 1898, Cleveland posted a record of 81-68. The next year they went 20-134. This does not happen in real Major League baseball. This is what happens in high school sports. Yes, there are teams that crater from one year to the next. Yes, they lost all their key players (Cy Young, Bobby Wallace, Cupid Childs, and Jesse Burkett). But still… that’s ridiculous. It makes the tanking of the late-20th- and early-21st-century Marlins look tame.

E. General conditions were poor. Players weren’t well-compensated, fields weren’t maintained. The general quality of the game was just… poor. Gloves were small or non-existent. Uniforms were strange. I suspect that, for the vast majority of us, the difference between 1895 baseball and 1901 baseball would not only be noticeable, but nearly as stark as the difference between high school and college baseball – even low-level, D3 baseball. You can tell that the quality of the players improves, as well as the field conditions, uniforms, games, etc.

Finally, I will concede that 1901 may not be the best place to put the dividing line: 1920 is probably better. But that’s not how most of baseball history has looked at itself. I think it’s okay to use some inertial reasoning, particularly when engaging in the task of revisiting the Hall of Fame selections of the BBWAA. Ultimately, as I said above, that’s what it comes down to for me. They included Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner? We include Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner. They ignored Wallace and Dahlen? We, or at least I, ignore Wallace and Dahlen. I’m not opposed to including them somewhere; I just don’t think they’re really markedly better choices than Dick Allen or Graig Nettles. Had they been overwhelmingly dominant, they way Cy Young was? Sure. But as it stands, I still don’t have any interest. I’d say I’m less militant and more open to the idea than I used to be, when I was more passionate about what I thought the COG should be, but as the process has gone along and I’ve seen players I wouldn’t have considered worthy go in, I’ve softened and decided that I’m happy to let happen whatever happens. If other folks don’t want to agree with me, that’s fine. If there are others who are more skeptical of 19th century baseball… well, all the better for the Ken Boyers of the world!

(PS: I thought I should mention this. bWAR sees no difference between Wallace (76.3, pitching inclusive) and Dahlen (75.3). But as I was exploring Fangraphs yesterday and the day before, I noticed that fWAR sees a pretty big difference between the two: 77.4 for Dahlen and 68.2 for Wallace. That’s nearly more than a 10-win swing from Baseball-Reference’s opinion if you’re comparing the two directly… and only 0.3 of that is explained by pitching, so that is NOT the answer. Just a thought for those who are having trouble deciding WHICH unworthy – he said, tongue planted firmly in cheek – 19th century SS they’d rather elect.)

Doom, You make some good points: The low point of 1901 was quickly repaired and in a few years MLB did cast a broader net for talent. (But 1901 was a low point.) The syndicate baseball year of 1899 produced the absurd anomaly of the Cleveland Outcasts, and competitive balance was disrupted as a result (though no other syndicate result was extreme, and 1899 was the only year of syndicate baseball).

Let me respond to your other points by number.

1. You say that the BBWAA didn’t vote for 19th century players because baseball then was “a different game.” I think there is no evidence that this is the reason they didn’t vote for 19th century players. In fact, they did vote for Keeler and Ed Delahanty from the start, and that sure wasn’t because of their 20th century records. I think it’s clear that some voters (Keeler wasa elected in ’39; Delahanty got over 50% in ’38) voted for those guys because they were great in the 1890s, and that no one was thinking in terms of whether 1890s ball was “a different game.” I don’t see any analogy to the Negro Leagues. I think the CoG goal was indeed to relitigate the BBWAA voting, and one of the first things to relitigate, for me, would be why Keeler (54.1 WAR) was elected and not his exact contemporaries Dahlen (75.2) and Wallace (70.2). Delahanty (69.7) was, of course, an earlier player than any of them.

2. I grant your main points, though if you’re going to lay stress on the abnormalities of one year, 1899, on one side of the divide, and use it to delegitimize all the years in that decade, I think you’d need to concede the poor quallity of average talent in 1901 and argue why that year doesn’t delegitimize its decade as well. (In fact, neither year delegitimizes either decade, but the low quality of 1901 does make it a poor choice as the year when baseball is suddenly no longer “a different game.”)

3. I think this is a grab-bag of irrelevant stuff. What difference does it make if uniforms varied or were silly (think of Bill Veeck’s White Sox in shorts!)? What difference does it make to the game if some teams played in multiple stadiums? In 1956-57, the Brooklyn Dodgers played some regular season games in an indoor stadium in Jersey City — how could that be in the modern game? Teams had multiple nicknames? So what — newspapers referred to teams by variant nicknames for years after; how does that affect the game itself? Yes, there are rare examples of games where fans were recruited out of the stands in the 1890s, and there were in the 1900s too. Players were poorly compensated and fields poorly maintained in the 1890s — and for two decades after. Gloves were universal among position players by 1893, with one exception (I think I recall that a couple of pitchers persisted without one into the mid-1890s), and their size and design changed gradually from then on — there was no leap in 1901 or thereabouts. The 1890s are, in fact, the era when baseball’s defensive skills coalesce, and the earlier defensive free-for-all comes to an end (of course, improvements have continued in every decade since). I think there is nothing to substantiate your claim that the game of 1901 was dramatically or even significantly different from the game of 1895: there’s just no evidence to support it. What there is evidence to support is that the game of 1890 was dramatically different from the game of 1895. I’m sure you must know the reasons why that was so.

In my view, you are as well or better informed about baseball than anyone else contributing to this site, and I don’t believe I know half as much as you. And you’re as free as anyone to vote as you choose for the CoG. If you find Dahlen and Wallace — and 1890s baseball — of little interest, then so be it. But I think when you support your lack of interest with arguments, they are not at all up to your usual standard, and I’d guess this may be precisely because the issue is one you are not deeply interested in engaging.

Fair enough. I want to make a couple of points.

First, about the grab-bag. I don’t disagree that this is a grab-bag; I don’t disagree that it’s irrelevant. However, think about this: do top-tier leagues share these features? They do not. They simply don’t; as quality of play improves, so do these other features; it’s inevitable. The game of the first decade of the twentieth century was radically improved from the game of the last decade of the 19th in all of these regards.

Second, a minor quibble: you say that I pointed to 1899, a famously rough year in the NL. I intentionally chose 1898, the year prior, because I didn’t want to use the story of the 1899, 134-loss Cleveland team. Each year in the 1890s had just as many anomalies.

The primary point I would make, though, is the point about who the voters considered. Yes, Keeler and Delahanty were both considered by SOME voters, but only Keeler and Young were ever elected by the BBWAA. The BBWAA did in fact know about the existence of the Old Timers’ Committee. The voters did not know about who was supposed to be considered by which committee; this explains Cy Young’s lack of support in the first election (he would’ve made sense in that first class otherwise, one would think). BTW, for what it’s worth, I didn’t vote for Wee Willie, even though the voters did.

My point with the Negro Leagues was not that the leagues were or weren’t analogous; it was that they share a feature: BBWAA voters did not consider these players to be in their purview. I simply wanted to do the same. Please, feel free to vote for them; I will not stop you, nor try to convince you. I just don’t plan to vote for them. I just can’t bring myself to do it; not yet, anyway. But feel free to try to convince me!

Well, Doom, if the series last spring didn’t convince you, or at least pique your interest, I think it would be futile to try to do so here. Really, that’s pretty much all I got. But the focus of the series was on changes in the game itself, not on the ancillary features that you take to be a certain index of game quality.

When you say, “Do top tier leagues share these features?” I think the answer in the 1890s is obviously, “yes,” and the answer in later decades is increasingly, “no.” But this is not a mystery: the game is in a steady state of improvement, always leaving some features behind decade by decade. The question concerns where the line can be drawn between Early and Modern, if it can be. When you look at the game itself, rather than the trimmings, it does appear that the line can be drawn, and the year is 1893. If you want to make the trimmings the measure, perhaps there’s another line to draw, although I don’t think it can be 1901, and I see no data that suggest any other — I think that after 1893, it’s all relatively steady evolution in quality until 1947-60, although there are certainly style changes that come and go, sometimes abruptly.

I blew by this really good exchange between you and Doom when it happened a couple days ago.

Something I’ve felt for a long time (and used to post about when I was here regularly) is that I believe that your characterization is roughly correct — that the quality of play has been going up over time, and that the curve is especially steep between 1947 and 1960. But I think it was also pretty steep between 1900 and 1930. I agree with Doom that 1920 might be as good a starting point as 1900. Things don’t really feel “major league” until you’re well into or coming out of the deadball era, and even in the 1920s and 30s, it was still pretty common for a replacement player to basically be a semi-pro, rather than pulled from a large field of just-below major league level players who were studying ad playing the game full time trying to make the show. Even major league regulars, if they weren’t stars, often weren’t paid enough not to moonlight or take off-season jobs.

Because of the history, and the reverence we have for the greats of those eras, I’m not willing to write them out completely, and I do think that you have to look at greatness in comparison to what people faced at the time to some degree. Yet I do look much differently on the 65-75 WAR accumulated by a deadball or even 1920-30s player vs. a player who played their whole career post-integration. I’m much more passionate about my choices among borderline 1960-2000s players, and I don’t/didn’t really support the candidacies of anyone pre-integration who doesn’t have inner-circle numbers or peaks. So yeah, of course, Musial and Speaker and Wagner and Walter Johnson/Cy Young/Cobb, etc. But I seriously wonder if even some of them would have put up more than 70-80 WAR against a replacement level comparable to 1960 or 1990 baseball.

This is why I never voted for Greenberg or Sisler either. I didn’t really follow the idea that we shouldn’t vote for Negro League greats. Paige ended up in, and I remember endless debates about Miñoso and Doby, Campanella (who ended up in) and Mosc’s favorite Monte Irvin, all of whose raw MLB stats run from clearly below the line to barely borderline, but I supported them, and if guys like Gibson or Rogan had ever had enough of a write-in following to get and stay on the ballot, I’d have been pushing them too.

In general I feel the same way as Doom, but I would go further and extend it to nearly all pre-integration players. I would prefer voting in any of our post-integration holdovers, including a couple guys on the second ballot and a couple more that can only come back in a redemption round to Dahlen and Wallace.

I also think Allen’s clubhouse cancer rep needs a bit of a review in light the casual racism that was pretty common in those days and, well, apparently still pretty common among a large share of the population today. Maybe he was an asshole. Or maybe he had a bit more human frailty and difficulty facing a still pretty gruesome situation than some of the paragons we worship from earlier times.

Anyway, that’s my two cents. I vaguely remember doing some analysis in comments years ago to try to figure what kind of WAR/WAA adjustments I should make as we were starting to get pre-integration players on the COG ballot. IIRC, it wasn’t impossible to finesse a range of reasonable adjustment.

A very thoughtful post, Michael. The point of view you’re expressing makes perfectly good sense, but I believe that the price of adopting it is to unnecessarily devalue baseball’s entire history, relegating it to a prelude to the present, which will someday in the future do the same to today’s players.

Baseball differs from other professional sports in the degree to which its history is expressed through the length, detail, and integrity of its statistical record. No other sport debates the relative worth of its history of players to the degree baseball does because the early data is too sparse and the games have changed too radically to provide a comparably even playing field for measurement. This, to me, is what makes baseball so supremely engaging.

If the question the CoG asks is, “Who are, in absolute terms, the best players ever?” then I wonder whether a single player from the eras before, say, 1950 or 1960 — or perhaps even later — would be elected. Not one of them had a training regime anything like today’s players; none had the nutrition or medical care; none of the hitters had to face a string of pitchers each game who were capable of throwing 90+ MPH, pitch after pitch; none of the pitchers faced hitters with the disciplined skills necessary to face such pitchers. Baseball has striven to get better every decade and it has. The realized abilities of the players, expressed in their stats, have always been 100% relative: relative to the quality of the competitive environment in which they played. It has to be so and it always will be.

I don’t think this vision of baseball as continually getting better was central to Major League baseball in the 1870s or 1880s. I think during those periods it was a peripheral thought. The main focus was on assembling talent — giving the ball to the hardest throwing or craftiest pitchers, having the best hitting team you could hire and letting it hit away, and keeping your fielders alert to respond to BiPs with concentration. A few team leaders, notably Charlie Comiskey, were early adopters of approaches like serious physical training and mastery of in-game tactics, but it was not until the early 1890s that the approach of continuous improvement through training, innovation, and strategy became universal, driving changes in the game ever since. That development also corresponds to the last of the major rule changes that gave baseball the look and structure of today’s game: the alteration of the diamond’s geography. My view, which I articulated at too great length in my series last spring, is that the new baseball approach pioneered by team leaders of the early and mid-1890s put baseball on the path to permanent improvement, in general making each decade seem obsolescent once it was past, and guaranteeing that no matter how extraordinary a player’s skills might be, within a few decades they would become an ordinary standard. Think how many pitchers today throw with acceptable accuracy at speeds beyond what Walter Johnson or Bob Feller threw at — are they all greater players? Think about what Babe Ruth’s career OPS+ of 206 — 106% better than league average — would translate into if that increasingly fat and pleasure-distracted player were playing in a Major League today, where a 100 OPS+ is so far beyond the 1920s/30s average hitter’s skill.

Players don’t get to choose the era they play in or the conditions that frame the training and competition they encounter. It seems reasonable to believe that had competition been keener in 1890, 1900, 1910, and so forth — more skilled and more strategic — the good players of that era would have raised their games to meet it. In fact, that is what always did happen, as baseball evolved for the better. Had Ty Cobb been forced to play in an integrated era with the best talent from the Negro Leagues and from other ball fields where, in the real world, talent had no opportunity to rise (and with the poorest of white Major Leaguers removed and relegated to the Minors), he would have faced greater challenges, and, I expect, being Ty Cobb, would have risen some distance towards overcoming them (and, I’m sure, would have become a better person as well). Well, perhaps, or perhaps not: the real world gives us only one version of baseball history. (And, as someone who pushed as hard as I could for Paige’s inclusion, despite CoG rules excluding him, I’d be happy to support an expansion of the CoG with Negro League player, so long as one or more of us studies up enough to help all of us make sure we vote responsibly.)

If we want to retain the meaningfulness of baseball history as a continuous body of statistical results and not just as a narrative of seasons, then I think we have to accept statistics across time as legitimate in their expression of accomplishment relative to era. Otherwise, all those post-1960 stars you feel enthusiasm for today will turn out to have been second raters when we reach the post-2060 era. We may or may not like the game of 2060 (I know I won’t like it, because I’ll never see it), but it’s a cinch that the game skills of the players will be a quantum leap beyond what we see in our present: the dynamic of MLB as a business and a sport ensures it.

I should be clear — I really don’t mean to take the tack that we should be looking at absolute value! In that case, you’re right that we’d probably have to ignore everybody that wasn’t outerworldly from before 1960ish, and how do you even know — is Ruth comparable to Barry Bonds, or Albert Belle, or some dude that never made it out of AAA?

So I still want to compare people to the era they played in, but I don’t like seeing what seem like inflated WAR totals based on the fact that replacement players were much further below the standards of the stars in those days than today (or any time post-integration).

When I talked about this a few years ago, as the original voting was getting to players who played a lot of their career pre-1947, I proposed an adjustment based on the difference between average and replacement for the years people played. This was also relevant to discussion of Hal Newhouser and a few other candidates who played during the war years and put up big numbers against reduced competition.

So for instance, Chipper Jones gets 327 replacement runs which is 30.8 per 1000 PAs, while George Sisler gets 35.4/1000 PAs. When talking about cross era comparisons, I’m not sure why we should be giving guys for their league having a wider difference between replacement and average.

And I think this still undercounts the difference pretty heavily, because the *average* player in 1900 was not a full time professional either, and the average standard went up dramatically post integration. I’d ideally like to be comparing earlier players to what “should have been” replacement level and average level” if the league had been full of pros with no color barrier. Now, how to do that statistically is not an easy (or probably even possible) question to answer, but that’s what I’m aiming for, not an absolute standard of play. By absolute standards (what would they do in today’s major leagues if you somehow time traveled them to 2019?), it’s arguable whether even Ruth/Williams/Young/Johnson/etc. get in, which I agree would be ludicrous and not what I’m talking about at all.

Michael, This sounds a lot more interesting. You seem to be interested in analyzing competitive balance, and for that we’d need to assemble curves for each season, plotting the distributions of OPS+ and ERA+. Wouldn’t the notion then change from a steady improvement of skills and performance to a more rapid rise in quality among the least talented, with average talent rising in quality faster than outstanding talent?

If that’s the model, wouldn’t we expect the highest career OPS+/ERA+ figures to come disproportionately from the early (or perhaps early and PED) eras? At a first glance, that does not seem to be a clear pattern in actual career leaderboads.

But this sort of math isn’t my area, so I’ll hope you correct my understanding. In principle, your idea seems on track to me.

(I think your idea would hold equally for the PED era. Those using PEDs changed the balance of competition relative to clean players, who more closely resembled replacement-level relative to the pumped leaders, even if median talent levels were, in absolute terms, holding steady.)

Main ballot-Boyer, Ashburn, Dahlen

Secondary-Dawson, Randolph, Helton

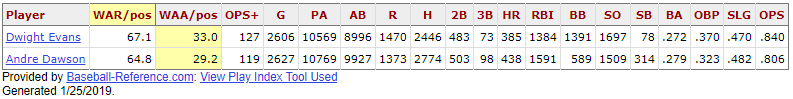

Before we get back to the dogfight over the same 10 or 15 marginally acceptable COG entries that have been on ballots for what is now literally years, I’m going to try to probe the worthiness for inclusion in this group of Bobby Abreau by comparing his record with that of someone already in the group, Dwight Evans.

Both played right field, both had long careers, both hit for medium power for their eras, Evans a little more. Other similarities: Both walked a lot, Abreau early in his career while with Houston especially, Evans later. OPS+ Abreau 128, Evans 127. Both performed better at home than away by about the same margin.

Despite the superficial similarities of some of their career statistics—they are very close in OPS+, as noted, but also in oWAR (61.6/60.5), Runs (1453/1470), Hits (2470/2446), RBIs (1363/1391)—they were dissimilar players in most respects. Abreau batted left, Evans right. Abreau stole 19 bases at age 24 and 21 at age 37, averaging 27 per 162 games. Evans was no threat on the bases, although he wasn’t a slow runner. Evans was much the better fielder, garnering eight Gold Gloves in ten years. It is this defensive superiority that gives him the final edge in career WAR, 67.1/60.0. Abreau hit for average early on, and at age 30 his cumulative BA was .305, which dwindled to .291 by career’s end. Evans at age 30 was batting .269, which he boosted to .272 by career’s end. And this difference is indicative of the telling fact that whereas Abreau’s career was made in his twenties, Evans’s career as a prominent force only began in his age 29 season.

Abreau has not been retired long enough for HOF consideration, but it seems likely that he will make a much more impressive show there than Evans, who was off the ballot after three years, his best total being 10.4% of the votes in 1998. Nonetheless, in his time Evans was, I think, regarded as a much more accomplished player, garnering MVP consideration 5 times, finishing third, fourth, seventh, ninth, and eleventh. Abreau, while making seven MVP ballots, finished no higher than twelfth, the other totals bringing him in 14th, 16th, 17th, 23rd twice, and 27th. JAWS ranks Evans fifteenth among right fielders—two positions above Ichiro, incidentally. Abreau holds the twentieth spot. As a cross check, per Dr. Doom, FanGraphs give Abreau 59.6 WAR, Evans, 65.1.

Well presented, nsb.

I was hedging on whether to give a vote to Abreu but, as you’ve demonstrated, he just seemed to come up a little short.

I’ve found the 65 WAR test (maybe 55 WAR for catchers) to be pretty reliable in guiding my selections. Most above that line seem to merit serious consideration as borderline candidates, most below somehow not.

Well-put, nsb. BTW, Abreu (0.7) and Evans (2.3) have two of the smallest differentials on the ballot between bWAR and fWAR. Only Dahlen (2.1) slides between them, with Nettles (2.3) having the same difference as Evans. Another player we’ll see this year in the balloting (Jeter, 0.2 difference); but he’s not here yet. The biggest differences belong to Tiant (11.2), Secondary Ballot candidate Ted Lyons (12.7), and Don Sutton, who is unrecognizable between the two systems at a difference of a whopping 16.7 WAR.

As for HOF voting, I expect Abreu won’t do much better than Evans did. I probably wouldn’t vote for him; I certainly won’t for the COG.

12: Amos Otis in his 23 and 24 age seasons comming from the Mets

PS: Q6: Postseason search is very difficult on BR;-)

Like you, I sure wish there was a P-I Season Finder for the post-season. But, question 6 is not difficult to solve with P-I Game Finder.

Indeed it is easy to find John Rocker with his perfect 0.00 ERA in 20 games with the P-I Game Finder :-/

But i didn’t even think about searching for a career stat with the game finder;-)

Of course, if you have the patience and wherewithal, you could create your own PI post-season finder.

This is Bruce Gilbert: my main ballot picks are Don Sutton, Ted Simmons and Dwight Evans. My Secondary threesome is Ted Lyons, Andre Dawson and Andy Pettite.

Doom has raised the issue of whether we should consult Fangraphs WAR. I have a very strong objection to fWAR for pitchers — I could explain those objections again, but I won’t — but it seems to me reasonable to consider fWAR for position players. Here is the list of the current main ballot position players, with fWAR indicated:

Abreu (59.6)

Allen (61.3)

Ashburn (57.6)

Boyer (54.7)

Dahlen (77.5)

Evans (65.1)

Nettles (65.7)

Ramirez (66.3)

Simmons (64.9)

Wallace (62.4)

Wallace has an additional 5.8 for his pitching, but since I don’t believe fWAR is reliable for pitchers, I have not added it in.

So, I started to write a comment about the dramatic difference in Simmon’s fWAR v. bWAR and what it might mean — perhaps fWAR takes framing into account (no), or some other stat that makes a big difference. I went over to fangraphs (which I don’t visit as often as b-r) to check on what exactly goes into their catcher WAR, and then look at Simmon’s chart to make sense of the differences, and what I found was that it was much simpler — looks like Bob made a typo — Simmon’s fWAR is 54.2 (needs a catcher adjustment to be COG material), not 64.9 (would normally represent borderline for any position player).

BTW, I agree with your objection to fWAR for pitchers. It assumes the pitcher has *nothing* to do with results on balls in play which seems absurd on it’s face, and isn’t really supported by sufficient evidence to take seriously as a measure of pitcher performance (BABIP year to year correlation for pitchers is low, but not effectively zero).

I do think there’s enough question about just how much effect a pitcher has on balls in play, that it’s worth looking at fWAR for borderline cases, but I take it much less seriously than I do bWAR. While for position players, it’s probably reasonable to average them.

You’e right, Michael: Simmons’ fWAR figure was a typo. Sorry! Wish I could get in there and correct it. (Doug . . . ?)

I agree with you on fWAR for pitchers. I think B-R takes the right approach by calculating the quality of the defense behind pitchers and adjusting on that basis. Although there are plenty of flaws in defensive stats and another layer of problems in applying season defensive stats in a blanket way, it’s certainly far better than evaluating pitchers without to BiP outcomes, which generally constitute more than half of each game.

OMG, I don’t think I can cope with this so sooooooon. Miguel Cairo does look tempting.

Must be those 150 games at 1B, 2B and 3B, putting Cairo in a group of 13 including luminaries like Pete Rose, Jackie Robinson, Paul Molitor and Matt Carpenter. Alas, Cairo more closely resembles the five others in that group who, like Cairo, also have 150 games pinch-hitting: names like Scott Spiezio, Ty Wigginton and Dalton Jones, the last famous for his PH exploits in the Red Sox pennant chase of 1967, but not much else.

Cairo and Spiezio sounds like a Personal Injury law firm. ‘Spiked at second? Call us to find out what your case is worth.”

~ 50 years later, I can still hear Curt Gowdy on his Saturday soap box speaking in ridiculously glowing terms about Dalton Jones. You’d have thought Jones was the second coming of Ted Williams.

Later, Gowdy switched allegiances and spoke about O’s prospects at Rochester (?), Grich, Coggins, Bumbry, and Baylor, etc…as if their super-stardom was a foregone conclusion and inevitability.

Well Grich is a pretty good call — if you choose a random 5 top prospects from a single team, what are the chances one of them becomes a hall of famer? Oh, right, those fsckers still haven’t put him in, so let’s say COGer instead.

Michael Sullivan

Well, actually, since even Coggins did contribute to some degree at the major league level, I guess Gowdy’s enthusiasm was warranted. However, I don’t believe I ever heard him speak of any other organization’s prospects in such glowing terms. IIRC, Hank Peters or Frank Cashen or whomever was running the show for Baltimore back then didn’t make too many mistakes in those days. Their biggest (and only ?) blunder may have been thinking Rettenmund was going to replace Frank Robinson

Curious splits for Dalton.

– as PH or 3B, 529 games, .265/.326/.379

– as 1B or 2B, 417 games, .215/.276/.323

There’s a little bit of double-counting in there, but this covers almost all his career. Seems like two different hitters. And, it’s not as if these are different periods in his career, as he played all of these positions throughout his career. Strange!

Doug,

That first split may have been good for an OPS+ greater than 100 in those dead-ball days…the second? Not good

The other odd thing is that each of the good slash figures is about 50 points more than the corresponding bad one. So, Jones walked about as often and had the same ISO in both situations; he was just a lot better at hitting singles as a pinch-hitter or third baseman which, in the case of pinch-hitting, sort of makes sense.

Vote Cairo! He was an original Devil Ray! He somehow played for 9 franchises in 17 seasons! He had two stints with the Cubs… and the Cardinals… and the Yankees! He had two different seasons in which he played first, second, short, third, left, right, and DH! He had double-digit sac bunts three times! More career WAR (7.7) than Willie Bloomquist (1.6)! He led the league in Range Factor per 9 among second basemen in 1999! He had the third-best dWAR in the AL in 1998! He once stole 28 bases (2000)! He nearly managed double-digit homers once (8 in 2011)! Vote Cairo!

Off Topic: Some of you may remember that I taped Jeopardy! a couple months ago. My show is finally airing – tomorrow, January 25th! If you are able to watch and cheer me on, I’d very much appreciate it. I’m Steven, the contestant on the right-most podium.

Glad you posted this reminder here, CC, since the CoG posts generally bring in a wider HHS group. Hopefully, some of our long-lost friends will return over the next day (or over the next few days, if they have cable access to past shows) and learn about your breakthrough as the first HHS regular to do combat on Jeopardy! I know the show was taped awhile back, but, nevertheless, Good Luck!

Thanks, Cursed. If I can get home in time, I’ll tune in and cheer.

Oh man. Is there a way to stream this? I cut the cord but I would love to watch this. What network is Jeopardy even on? I’ll find some way to watch it tonight!

For people without TVs, I have a link to the episode on Dailymotion I can post after it airs.

Please do, would be fun to watch.

First post in this reddit thread has links: https://www.reddit.com/r/Jeopardy/comments/ajmf2m/jeopardy_recap_for_fri_jan_25/

Very nice! Congrats! So you’ll be on again as the champ? Love the confidence and game theory with your bid on final to guarantee the win if you get it right.

Hey, Jeopardy question, as someone who’s clearly pretty good at the game, if you don’t mind answering: For playing successfully, based on your sample size of presumably one to a few rounds — How would you balance the value of these various things in percentages or ratios:

1. Knowing the answers (at least within the time limits)

2. Knowing the answers instantly or super quickly.

3. Timing the buzzer to get in.

4. Game strategy (question picking, bet sizes),

5. Avoiding performance jitters.

6. some important factor I’ve failed to mention.

I haven’t watched the show in years, but I’m always fascinated by games and strategy. I have a suspicion that buzzer timing is really important, since I often know most of the answers, and it seems as though all of the good players like you do as well. Even Christopher, who was clearly a step behind you and the other guy, seemed to be pretty solid — I get the sense they rarely pick contestants who aren’t really good at trivia in general.

I’d say about 60% buzzer, and then a mix of knowledge and nerves. Like you noted, everyone on the show knows a ton. It’s all about being able to buzz ahead of people, and keeping your cool so that you don’t blank on the things you know.

Does the buzzer penalize you for buzzing early? Is there some deterrent for buzzing before the question is complete?

CC

You da man! That was some second half performance by you! I’m a little surprised no one else got the final jeopardy question correct but no matter since you wagered enough to cover even a correct answer from them. Again, congratulations!!

I think a lot of the questions I would know the answer but I could never formulate it that quickly. I get tongue tied so easily. Especially under stress, it’s a staggering skill.

I loved “Pikachoooooo”! I’m glad they didn’t make you answer that as a question.

Steve-O! I had to drive across Canada for a funeral last weekend so even though I had it marked in my calendar I had to catch up in the last couple of days. Congrats on a good run! Very close on the second game too, if you had gone into Final with the lead you would’ve got it, but a worthy opponent. As someone who has friends that are Jeopardy fanatics, it was exciting to tell them about it and have someone to root for.

This is going to be a long one:

Here is a comparison of some essential career stats of this round of contenders for the Circle of Greats versus those of select COG members —those who aren’t in the HOF, who aren’t currently ineligible for the HOF, and who aren’t named Bonds or Clemens.

First, position players.

WAR, PA, and OPS+ mean just what they say.

HOS is the rating given to the player at Adam Darowski’s Hall of Stats.

The final stat is my own corrective to what I see as the tendency of both WAR and the HOS rating to over-value career longevity: WAR per plate appearance ( x 10000 to make it easier to comprehend in a chart).

Player———–WAR————-PA——- OPS+—HOS—-WAR/PA

_______________________________________________________________

Grich———–70.9(16.8)——8220——125——140——86.25**COG

Whitaker——74.9(16.3)——9967—–117——145——75.15**COG

Walker———72.4(2.0)——-8030——141——152——90.16**COG

Lofton———68.2(15.5)—–9235——107——133——73.85**COG

Allen———-58.7(-16.3)—-7315——156——117——80.25

Ramirez——69.4(-21.7)—-9774——154——130——71.00

Nettles——-68.0(21.4)—-10228—–110——126——66.48

Ashburn—–63.9(5.4)——9736——-111——119——65.63

Evans——–67.1(-3.8)—-10569——127——124——63.49

Boyer——–62.8(10.7)—–8272——116——118——75.92

Simmons—50.3(5.2)——9685——-118——112——51.94

Dawson—–64.8(1.6)—–10769——119——123——60.17

Randolph—65.9(20.2)—–9461——104——124——69.65

Helton——-61.2(-5.5)——9453——133——120——64.74

Abreu——-60.0(-11.1)—10081——128——110——59.52

Now the pitchers.

The relevant stats here are WAR, IP, ERA+, HOS rating, and pWAR per inning pitched (x 1000) again to be a slight corrective to overvaluing career longevity.

Player———-pWAR——-IP———-ERA+—-HOS—-pWAR/IP

_________________________________________________________

Ferrell———–48.8——2623.0——116——112——18.60**COG

Schilling——–80.7——3261.0——127——171——24.75**COG

Brown———-68.4——3256.1——127——137——21.00

Tiant————66.1——3486.1——114——129——18.96

Sutton———-68.6——5282.1——108——112——12.99

Lyons———–67.6——4158.2——118——126——16.26

Reuschel——68.3——3548.1——114——136——19.25

Pettitte——–60.7——3316.0——117——108——18.30

Hope this comes out all right and makes some sense as a means to see not only how candidates match up with one another, but how they compare to some players already chosen.

What it does not do is fill in the details of each players virtues and liabilities: Ferrell’s batting prowess, Ramirez’s considerable baggage, etc.

nsb, I notice Dahlen and Wallace are not included on your list. Here are their stats (I assume the parenthetical figure next to WAR is dWAR):

Dahlen——-75.2 (28.5)—-10411—-110—–145—–72.2

Wallace——70.2 (28.7)——9617—-105—–145—–73.0 . . . (pitching 6.1—402—-125—-xxx—–15.17)

Right. The chart took so long to lay out that my brain failed more seriously than normal, and I forgot to mention those facts. Nothing against the dead-ball guys—I just wanted to focus, to be honest, on the way the live-ball position players don’t match up to the live-ball COG inductees not in the Hall. With the pitchers, the ‘pitchur’—as we illiterati say—is clouded by Ferrell’s inclusion, since his hitting put him over the top.

The question of how we should view career longevity is not simple. In general, we could think of comparing players with comparable qualifications for the CoG and significantly different career lengths as a contest between a player making his case on the basis of the high quality of his realized potential and a player making his case on the basis of total accomplishment. There is something to be said for each measure, and nsb’s table gives us both. (I’ve been using WAR per G and qualifying season for rate measures in my tables, but I’m jealous of nsb’s approach because, for hitters, his figures put the cumulative and rate stats on the same scale.)

In recent CoG rounds, I’ve been increasingly tempted to vote for Dick Allen (and may have done so) — his WAR rate, as nsb shows, is terrific, leading everyone. But Allen’s high rate is a product of a short period of decline: he essentially walked away from the game at age 35, in part because he was fed up, but probably in larger part because he was washed up. After age 32, he produced only 0.4 WAR over three seasons (1020 PA, about 14% of his career). That sort of an ending reduced his total accomplishment, but it also preserved most of his high rate-stat profile.

By contrast, in his age 36-40 seasons Graig Nettles (whom I haven’t voted for, but who makes a nice contrast) produced 11.6 WAR (compared to Allen’s zero): a substantial contribution, but well below his rate in his prime. (He also stayed too long, contributing -0.6 WAR in age 41-43 seasons he might have done better to forego.) If you compared Allen and Nettles, counting Allen’s age 36-40 WAR as 0.0 (or age 36-43, to be more complete), I don’t think that would give us a better way to look at Allen vs. Nettles, but I think it would add a perspective of some value in making a well reasoned comparison. (Of course, Allen’s real WAR in those seasons wasn’t 0.0, it was X.X, but a numerical notion helps the thought experiment.)

It’s interesting; I guess I would argue that WAR itself already accounts for playing time on a seasonal basis. I mean, there are two reasons to use WAR rather than WAA. First, average players have value. A team made up entirely of average players will nearly make the playoffs – add in another star, and you’ve got a good shot at a Wild Card. But the second reason to use replacement rather than average is that it accounts for playing time. Is it better to be 50% better than average and only play 50% of the season, or is it better to be 20% above average and play the full season? WAR can answer those questions more satisfyingly than WAA.

When we’re looking at a career rate, I guess I would argue that looking at WAR in rate form is not really the most effective way of looking at it, since WAR itself already accounts for disparities in playing time. Bob, in the example you site, Dick Allen’s 36-43 WAR was 0.0 – he didn’t contribute anything. You can certainly look at it as a rate stat… but why bother? Better, I think, not to punish Nettles for ages 42-43, and just compare them through age 41. Why bother checking rates at all? We know how much WAR they accumulated through that age. That puts Nettles 10.1 wins ahead. You don’t have to modify it or look at it as a rate stat. (Incidentally, if you look at Fangraphs, the gap is only 5 WAR; but that’s not the point here).

Another way to look at it is to take players only during those seasons in which they overlapped; there are MANY weaknesses to this approach, as I’m sure you don’t need me to explain. But both Nettles and Allen were in the league ages 22-35. In that period, Allen out-WARs Nettles 58.8-56.9. This approach doesn’t “punish” Nettles for hang-on years. On the other hand, Nettles was in the league ages 22-24, but didn’t play 100 games until his age-25 season (he played 96 as a 24-year-old). Still, maybe 24-35 is more fair. In that span, Nettles out-WARs Allen massively: 55.9-43.6; of course, we’ve also eliminated two of Dick Allen’s top 4 seasons in so doing, simply because Nettles was not effective at those ages, which hardly seems fair.

Point is, there are lots of ways you can slice it to account for this difference. There are those who favor WAA+, or a JAWS-style system in which you look at top 7; when Bill James did the NBJHBA, he did a weighted average of total, top 3 overall, and top 5 consecutive; Hall of Stats combines WAR and WAA. I have my own method of weighting, which, incidentally, has those two almost exactly equal: 67.2 for Allen, 67.0 for Nettles. That’s a total wash. But then, that’s because I try to give peak credit by weighting peak seasons more, in a similar (but better, I would argue) way to those methods listed above. (My proudest moment as an online baseball nerd was having my method displayed on Tango’s Hall of Fame selector; you’ll find it as fDoom for Fangraphs WAR or rDoom for Baseball-Reference WAR. I will never be tired of the fact that it exists that way.)

In conclusion, there’s really no way to do this perfectly, but I don’t think WAR as a rate stat really does what we want it to do. The statistic itself, on a seasonal level, already accounts for differences in playing time. On a career level, it’s not perfect, but I think WAR still does a good job of accounting for different career lengths.

What a well thought, cogent post! I’m going to have to catch up over time to really test out some of your ideas so that I fully understand them, but you carried me along well enough for a first take.

One detail: I do think assuming that a non-playing player earns 0.0 is only a strategy of convenience. As you say about Allen in his post-age-35 seasons, he was contributing nothing. But a player with 0.0 WAR contributes at replacement level. They’re different levels of contribution, I think. I’d be thrilled to think I’ve racked up scores of 0.0 WAR seasons; if you put me on the field for an actual inning, I’d be in negative territory the moment I appeared at the plate or had a fielding chance.

I think the consensus is that below average WAR is mostly the Team’s fault. They do not have the talent or the analysis to deploy what is expected as a major league level minimum. I discount any negative WAR from a player’s career. I find it unnecessarily cruel. If the team wants the player to play, they must think he’s better than a replacement. If he’s not better, that’s on the team.

To me, WAA is very valuable for this specific conversation. You’re not talking about comparing players that are on either side of average, you’re talking about comparing the dominance of history’s finest against each other. The “bar”, so to speak, can be raised. Replacement level won’t cut it. Average won’t really cut it either (but it does make a nice bar). How much BETTER than your average ballplayer were these guys, and for how long.

WAA+ removes the negative again, you’re only looking at their positive contributions. History’s best tended to love the game and their talents were often visible at a young age. That means they often debut’d before they were stars and played for years afterwards. WAA+ nicely focuses on their contributions that exceed the norm.

I agree with Doom, although not exactly his statistical flavoring, that the impact of a player’s peak is more meaningful than their career accumulation. A player’s best is what they did at their best and that is not a 20 year period (unless you’re Willie Mays). In addition to WAA+, I like weighting peak years.

No stat is perfect. You still have to adjust for lots of other factors. Defense stats sucked before 2013 or so IMHO and only make sense on a 3-year average. Steroids helped those who used them and disadvantaged others. Racism, not a lack of talent, played a role in the career lengths of too many all-time greats. Coors field (pre-humidor) breaks the statistical model and is too much of an outlier to not address. There are many other things to keep in mind as well.

But yeah, I like rDOOM too.

mosc, I take WAA+ into account as one measure I consider (entirely because of your repeated arguments, which I think have merit). But I disagree that it is the fault of the team and not the player when he earns negative WAR. Perhaps I really don’t understand the argument, since you say it may be a consensus one.

Look at Albert in recent years. Of course the Angels could let him go and eat his contract, but they’d have to pay additional money for a replacement, and while a replacement might be better, if it’s a new player that’s a gamble, if it’s an established player the cost goes up further for a team stretched thin by Albert’s contract, and in either case the Angels lose the attendance that Albert still draws. It is a difficult call for the Angels. Regardless, Albert is out there playing lousy baseball, sometimes above AAA-level, sometimes below, and he is perfectly free to call it quits. Clearly, he cares more about the salary than damage to his record, and, honestly, so would I (although I think the impact of those paydays may be a tad less strong for Albert than it would be for me).

The team offers the player the job. He has the option to take it or refuse. If he takes it (and while most players in history have needed a job, the elite level we’re speaking of here generally had a bit more leeway — higher salaries for years and a reputation that can help the transition), no one is performing his job but him, and I can’t see anything cruel about assigning and counting negative WAR (or WAA). The outcome is what actually happened on the ball field. It’s a stretch to say the player’s being exploited, unless, somehow, he’s receiving a salary below the level of his total contribution (on the field and to the ticket office).

On the other hand, if you want a snapshot of the basic quality of a player — how much reward you’d get for the price of a ticket to see him when he was in full possession of his talents — WAA+, along with peak stats, can sketch that profile for you in one number better than career WAR or WAA.

I think there’s no “right” answer about how we should assess a fine player’s down seasons; they’re part of the full picture, and we want that full picture as context when we focus on its various components. The weight we choose to give the negative years is a subjective choice, based on what we choose to prioritize in evaluating players.

I would say that there’s consensus that negative WAR is the team’s fault. Negative WAA is a different story. That’s mostly a contrivance I use when looking at all-time greats. I wouldn’t use WAA+ to compare single season excellence or evaluating a team’s performance.

I don’t like negative WAR. It’s mathematically necessary don’t get me wrong but I think it’s a little unfair.l

I mean, you can’t punish him for not playing, right? Ted Williams lived into his nineties and spent much of that time in a wheelchair. We obviously don’t take away wins for that, nor do we punish for once upon a time having been eight years old and inadequate baseball players. WAR is measuring how much or little someone contributed to winning or losing. If you didn’t play, you didn’t contribute, nor did you hurt. So you get zero. It’s the same logic that says you shouldn’t punish Nettles for playing for teams desperate enough to play him in his forties. So I would say the only fair thing is to that nothing as zero.

Ferrell makes for a bit of an unusual comp here, because there’s no way he gets voted into the COG or even taken all that seriously for it without his 11.8 batting WAR. If you count that in, his WAR total is 60.6, right behind Pettitte, and his WAR/1000IP is second to Schilling and ahead of all the current ballot members at 23.1.